[ad_1]

Most Saturday mornings Abby is at work or walking in nature somewhere. But on July 2, the 30-year-old is waiting at her house to be picked up by an acquaintance who will drive her more than two hours to a clinic in Illinois to obtain a medication abortion to end her pregnancy.

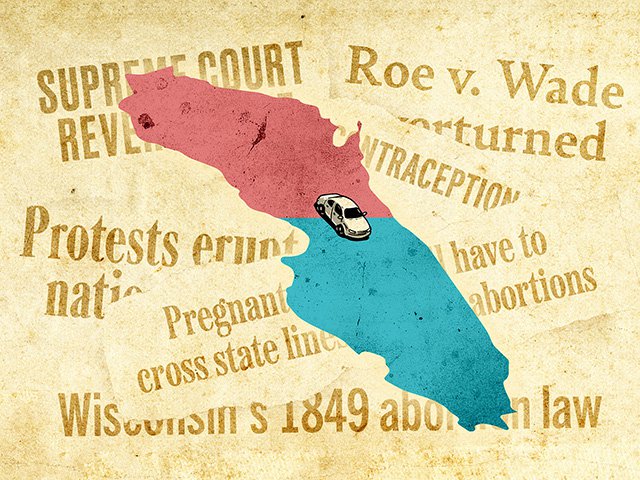

Even two weeks ago, Abby — who allowed a reporter to travel with her to Illinois and share her story but requested that her real name not be used — could have obtained what is commonly referred to as the “abortion pill” at the Planned Parenthood of Wisconsin clinic in Madison, where she lives. But when the U.S. Supreme Court issued its June 24 decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, overturning the constitutional right to an abortion that has existed since 1973, Planned Parenthood clinics immediately stopped offering both surgical and medication abortion due to Wisconsin’s 1849 criminal abortion ban, which is still on the books.

Wisconsin Attorney General Josh Kaul has since filed suit in Dane County Circuit Court to block the 173-year-old statute. But Wisconsin women seeking abortion must currently go to Illinois or Minnesota or one of the other states in the nation where abortion remains legal and accessible.

Abby’s boyfriend could not get time off from work to be with her for the appointment so a good friend of his, Lili Luxe, is driving Abby instead. Luxe pulls into the couple’s driveway just before 9 a.m. and Abby walks out holding a pillow and sweatshirt. The pillow, she explains later, is her “comfort.”

“I bring it on any road trip,” she says. The sweatshirt is so she’ll have “something cozy” to wear on the ride home.

Abby piles in the backseat and Luxe offers her a fresh donut she picked up on the ride over. Luxe has also brought along popcorn, gummy bears and other snacks, in addition to some items she thought might work as distractions should Abby want them: crossword puzzles and coloring books. She was also advised by Dana Pellebon, the co-executive director of the Rape Crisis Center and a Dane County board supervisor, to bring Abby a stress ball — “So she has something to hold that is grounding and comforting,” says Luxe.

Abby says she is nervous — not about the choice she is making to end her pregnancy — but about the medication she will be taking to make that happen. “I just want to be okay,” she says. “I don’t want any complications. Going to the doctor is not really a calming place for me.”

Abby keeps track of her periods on a phone app. Since the Dobbs decision she has heard the concerns about such apps making it possible to track women seeking abortions in states where they are illegal, but she finds the app handy and full of useful information about such things as ovulation and period relief. This month her period was late and she also started to experience telltale signs of pregnancy: extra tender breasts, sore nipples and mood swings. On June 28, she took an at-home pregnancy test; it was positive. She figured she was about five weeks pregnant.

Abby called her boyfriend, who was at work at the time. She says he was supportive of the decision she had already made. “I’m not ready,” she says. “I don’t really want kids now. I’m trying to work on my mental health now.”

Her boyfriend called Luxe for guidance on how to help Abby access an abortion out of state. Luxe, a longtime activist on issues of sexual freedom and consent, says people often turn to her as a resource. Luxe called Pellebon, who gave Luxe some names and numbers.

Abby says she spent about four hours that day calling clinics in Illinois, but could not get through or was put on hold — up to two hours at one clinic. She started to feel a bit panicked but then her boyfriend got through immediately to a clinic in the Chicago area. He handed the phone to Abby and within a few minutes she had an appointment for Saturday.

Abby says she was asked whether she preferred a surgical abortion or medication abortion, generally available up to 11 weeks of pregnancy. She chose the latter and was told about the process and risks. “It was really informative and made me feel comforted,” she says. She was also informed that clinic personnel would go over all the information again at her appointment.

The clinic followed up with an email confirmation, information sheets, and consent forms Abby was to sign and bring with her on the day of the appointment, along with her insurance card and identification.

Abby says she felt an immediate sense of relief when she got off the phone. But she also was thinking about other women who might be facing a similar predicament. “I’m feeling for the women who don’t know how to access [it],” she says. “I can’t imagine what it’s like for people who can’t drive to a different state.”

Luxe and Abby arrive about 45 minutes early for Abby’s appointment. Located along a busy suburban road, the clinic asked not to be named due to the shifting legal landscape on abortion.

The clinic had told Abby to expect that anti-abortion protesters would be outside the clinic so she is not surprised to see a dozen or so people clustered on a patch of grass between the street and parking lot. They have set up signs on the sidewalk terrace and against a car parked on the street: “Stop abortion now” and “Ask me about a free ultrasound.”

Abby decides to see if the clinic will get her in early. She was told because of COVID precautions she could not have anyone with her, so she grabs the stress ball Luxe has given her and goes in alone.

By the time Abby gets out of the car to enter the clinic the gaggle of protesters has shrunk to four men. One, wearing a front baby carrier with a children’s doll in it, repeatedly screams “repent.” Abby recalls later that she heard one protester yelling that “there’s a reverse abortion pill,” something that hasn’t been proven in reliable medical studies.

Another man, who would only give his name as John, says he and his fellow protesters are driven by their “spirit who says this is not right.”

That’s what separates people who support and oppose abortion, he says. “One of the differences is that we do believe in God. We do believe that life begins at conception.”

John says his ability to freely express his views is “what makes this country so great.” But he declines to comment on whether his views should dictate law. “I won’t get into that. It’s whatever people voted for, correct? Everybody is all upset about Roe v. Wade. It just took it out of federal hands and put it back into the state’s hands.

“Your state of Wisconsin — if that’s where you’re from — has deemed it illegal. Illinois wants to be the abortion center of the country. Isn’t that sad? It is to me, anyway. Wisconsin boasts about recreation and tourists and we’re going to boast about, ‘Come and have an abortion?’”

Abby texts Luxe within 15 minutes to let her know that she got in early and has already had a vaginal ultrasound that confirms she is about five weeks pregnant. She is now back in the waiting room, waiting for her medication to be prepared and to meet with the doctor. About 30 minutes later she is done.

“The doctor was amazing,” she says. “I can’t get over how nice everyone is and how calming they are.”

Abby took one pill in the office — mifepristone — and was instructed to insert four tablets of misoprostol in her vagina within 24 hours. The two-step regimen is typical for medication abortion. The clinic also tells her to make an appointment through Planned Parenthood or her health care provider to get an ultrasound in two weeks to make sure that the abortion is complete.

Her total cost is $625, which she is asked to pay before receiving services. She plans to see if her insurance company will cover any of the costs. She also plans to change her birth control. For medical reasons, Abby can’t take estrogen, so she has been on minipill, a progestin-only type of birth control that is taken daily. She realized, at some point, that she somehow missed two days. She doesn’t want that to happen again: “I am going to contact my doctor and see about a different form.”

The need to travel to Illinois for a medication abortion added several obstacles for Abby that did not exist for Madison residents before June 24: travel that took the better part of a day; the need for a car and driver; and money to cover the cost of gas — about $70 — in addition to the procedure.

But there was one silver lining: The process for abortion in Illinois is much more streamlined than it would have been at a clinic in Wisconsin due to restrictions passed in recent years by the state Legislature. Wisconsin has a 24-hour waiting period to receive any abortion and, in the case of medication abortion, a requirement that the same doctor see the patient for the initial visit and to administer the first dose of the drug. “On average most patients would wait about a week between the first and second visit,” says Dr. Allie Linton, associate medical director of Planned Parenthood of Wisconsin, which until June 24 operated three clinics in the state that offered abortion.

Linton says it was always a challenge to sync the appointments to match both the doctor’s and patient’s schedule. Sometimes a delay would mean that patients who originally sought a medication abortion would have to get a surgical abortion because, during that time, their pregnancy progressed beyond 11 weeks; it also meant that sometimes women missed the 22-week cut-off for surgical abortion in Wisconsin (20 weeks at Planned Parenthood clinics) and would have to seek an abortion in another state.

“Any time you have a waiting period you risk taking away options,” says Linton.

Women across the country have already been self-managing their abortions at home by ordering pills online and more are expected to pursue that route now that Roe v. Wade is no longer the law of the land. When lawmakers in Texas banned abortion after six weeks of pregnancy in September 2021, orders for medication abortion from Aid Access, a nonprofit based in Europe, went up 1,180 percent in the first week, increasing from about 11 orders per day to about 137 per day, according to a study in JAMA Network Open and reported by Politico.

Orders did decrease after a few months but, according to the study, were still considerably higher than before the restrictive Texas law took effect.

Aid Access provides counseling from a doctor and help desk before, during and after the process, according to its website. A doctor provides the prescriptions for mifepristone and misoprostol and a pharmacy in India ships the medicine, with delivery between one to three weeks. The cost is $110.

For the duration of the Texas study, led by a researcher at the University of Texas-Austin and conducted between Oct. 1, 2020, and Dec. 31, 2021, the state had a law in place banning the use of telemedicine to administer medication abortion; in January 2022, Texas passed a new law requiring physicians to examine patients in person before providing abortion medication and banning the delivery of such medications by mail.

Under Wisconsin’s 1849 criminal abortion ban, it is not a crime for the woman to have an abortion; it’s a crime for a doctor to provide it.

Like Texas, Wisconsin prohibited telemedicine abortion even before the Dobbs decision came down from the U.S. Supreme Court. So for people in Wisconsin to legally access abortion pills from an online provider, the pills need to be sent to an address where telemedicine abortion is legal, like Illinois or Minnesota, says Jessica Dalby, a family doctor at UW Health who is on the steering committee of Pregnancy Options Wisconsin: Education, Resources & Support Inc. (POWERS).

Aid Access, however, will buck those rules, she says.

“Aid Access has been sending pills by mail to Wisconsin residents since 2018,” says Dalby.

Dalby and Linton do not have concerns about women taking abortion pills in the absence of a physician.

“We do know that self-managed abortion, especially when sourced from reputable sites, is safe and patients are able to manage their abortions at home,” says Linton.

“The pills are very safe,” agrees Dalby. “Even when you get pills at a clinic, you’re basically doing the same management at home.”

“I think the biggest risk of self-managing,” adds Dalby, “is the prospect of it going away.”

[Editor’s note: Lili Luxe works as a court reporter for Dane County Judge Rhonda Lanford, who is the author’s wife.]

[ad_2]

Source link