[ad_1]

The energy crisis triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, along with high inflation and rising interest rates, sparked concerns of an economic downturn in the eurozone this winter. But Toni Ruiz, chief executive of Spanish fashion retailer Mango, said sales were proving the pessimists wrong.

“After months, years of Covid, people wanted pretty, elegant outfits,” Ruiz told the Financial Times. “People were tired of basic clothes. So what we’ve seen is an enormous take-off.”

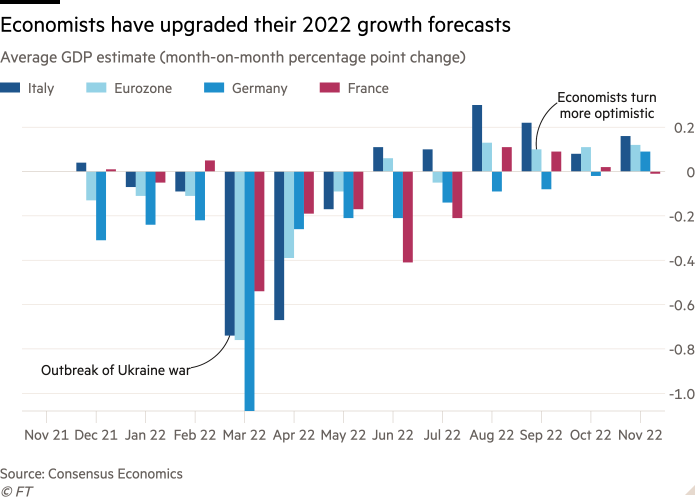

Across the region, sentiment has rebounded. Low unemployment, greater fiscal support from governments, a drop in energy prices from their peak in August and a mild autumn that has helped keep gas storage facilities filled over the summer close to capacity, have all improved the outlook.

António Simões, head of Europe business at Spain’s biggest lender Santander, told a conference this week: “I’m concerned like everyone else, but more with a view of the glass half-full.”

Even in Germany, where manufacturers were hit hard by soaring energy costs caused by reduced supplies from Russia, there are signs of a cautiously more upbeat mood among businesses.

“Production in most industrial and services sectors has held up very well despite the energy price shock,” said Klaus Deutsch, head of research, economic and industrial policy at Germany’s BDI business association. “There’s a big backlog of orders so there is still some work to do even if demand falls.”

The BDI told the Financial Times it had been “too gloomy” and was likely in January to raise its forecast from September for the German economy to grow 0.9 per cent this year. The Ifo Institute’s index of German business confidence bounced from 84.5 in October to 86.3 in November, while the Munich-based think-tank also found three-quarters of companies that use gas in production had reduced their consumption without cutting output.

Most economists still expect the eurozone to slide into a mild recession — defined as two consecutive quarters of falling output — and central bankers are warning they will have to raise borrowing costs again in December.

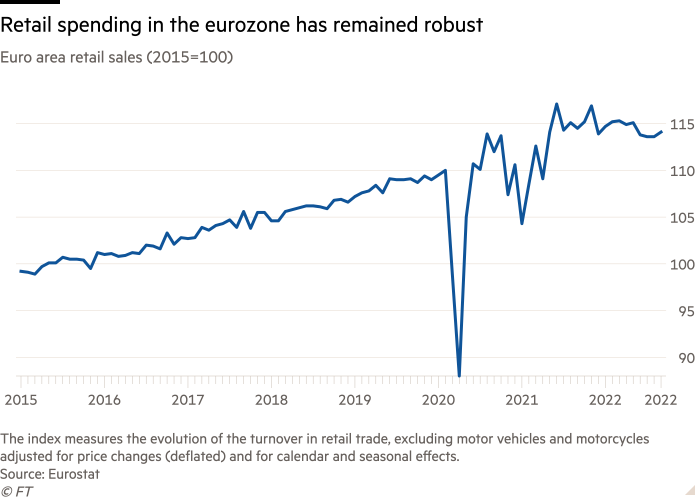

Yet, after resilient third-quarter growth of 0.2 per cent in the 19-country bloc, there are signs many may have overestimated the drag on consumer spending and industrial output from high inflation and underestimated the boost from lifting Covid-19 restrictions.

Retail spending rose 0.4 per cent in the eurozone and wider EU between August and September, while industrial production was up 0.9 per cent in the same period, taking both measures further above pre-pandemic levels.

The EU’s monthly survey of companies and households, published on Tuesday, showed economic sentiment had risen more than expected to a three-month high. Consumer confidence across the EU rose as people became more willing to make big purchases, while services companies expected higher demand and industrial groups grew more upbeat on production expectations.

Members of Germany’s Dax index of blue-chip companies are on track to pay record dividends next spring, according to research published by business newspaper Handelsblatt on Tuesday.

The eurozone’s industrial powerhouse has not emerged from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine unscathed. Output has fallen in energy-intensive sectors that are particularly exposed to higher gas and power prices, such as chemicals, paper and glass. But these sectors only account for 4 per cent of Germany’s economic output and many companies have been able to offset the blow with higher prices.

Although Mango’s raw material costs had fallen recently, Ruiz said he expected inflation to remain a problem for the fashion chain for two or three more years, noting it was experiencing sharp rises in staff, rent and electricity costs at its 1,700 stores across Europe.

An executive at one large German group warned households still had not seen the full impact of the surge in energy costs. He noted that it would take until March 2023 for products that were produced in September, when energy costs were still close to record highs, to be bought by customers.

But even on inflation there has been some good news. Consumer price growth appears to have peaked, with inflation falling from a record high of 10.6 per cent in the year to October to 10 per cent in November.

In France, worries about energy prices, exacerbated during a fuel crunch in October when refinery workers went on strike, have lifted slightly. Business leaders became more upbeat about the outlook for the first time since July, according to a survey of more than 600 company chiefs published this week by CCI France, the country’s chamber of commerce federation.

Healthy order books in the construction sector and across other industries, coupled with easing bottlenecks in some supply chains for components and dropping raw material costs for inputs such as steel, had fuelled the turnround, CCI France found.

Italy’s industrial trade association Confindustria said output had held up well in manufacturing and services, although the construction sector had ground to a halt. But some of the association’s gloom had merely been postponed until next year. A slowdown induced by “higher interest rates and lower liquidity due to higher utility bills” was likely for 2023.

Others agreed that next winter was set to be tough. “We are seeing indications of gradual improvement,” said Rolf Hellermann, head of finance at German publisher Bertelsmann. “[But] gas supply in Germany and the build-up of storage might prove to be more challenging [next year] than in 2022, given much lower inflows from Russia.”

Additional reporting by Patricia Nilsson, Sarah White and Silvia Sciorilli Borrelli

[ad_2]

Source link