[ad_1]

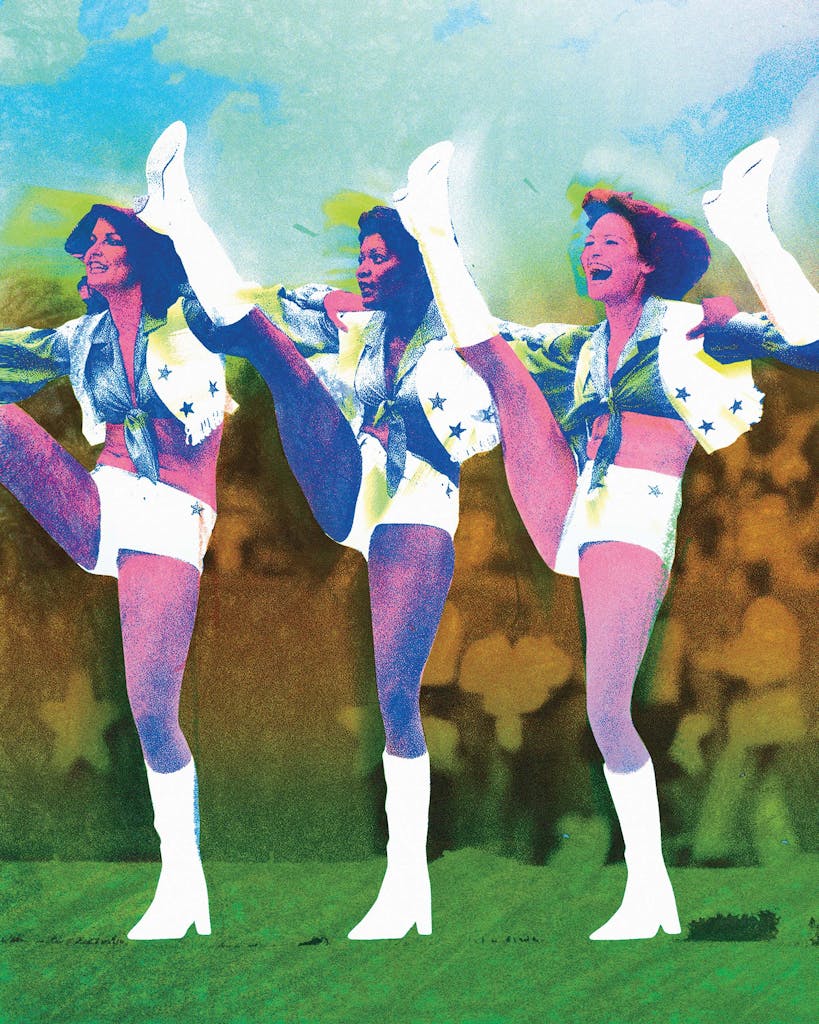

On a sweltering Saturday in August, seven cheerleaders stood in the tunnel of the new Texas Stadium, just beyond the city limits of Dallas, wearing a uniform unlike anything that had ever been seen in professional sports: White go-go boots that zipped up the front. Teensy white hot pants. A plunging royal blue crop top knotted at the rib cage, just one suggestive tug from coming untied.

This was 1972, and Vonciel Baker was nervous about the crowd. The twenty-year-old was short and skinny, and she used to shimmy to James Brown in her living room as a kid. She was one of five raised by a single mom in South Dallas, on the wrong side of the tracks in a status-obsessed city, but Baker had a quality you might call sparkle. Earlier that spring, she’d heard a radio spot on the local station KVIL announcing that the Dallas Cowboys were looking for a new kind of cheerleader—dancers, that was the idea. More than a hundred showed up for tryouts; only seven made the cut. (Actually, eight did, but an aspiring model dropped out before the season began.) They would become known as the Original Seven: Baker, Anna Carpenter, Rosemary Hall, Dolores McAda, Carrie O’Brien, Deanovoy Nichols, and Dixie Smith. Each of them stood in that tunnel, staring at the artificial turf and the stands of a new football stadium named for the state whose glory it hoped to capture.

The Dallas Cowboys had had cheerleaders before, including a group of high schoolers in bobby socks and pleated skirts who yelled “Charge!” They didn’t dance, and they didn’t wear that. It’s tough to remember in our skin-saturated age, but cleavage and bare midriffs weren’t just unusual back then—they were scandalous. This moment in 1972 marked the debut of a bold experiment, a very Texas hybrid of pageant beauty, good-girl etiquette, and come-hither slink.

Baker looked up at the sky whenever she got anxious, and she could see the sunlight fading and the stadium lights blazing from where she stood in the mouth of the tunnel. Texas Stadium had a hole in the roof, a design quirk (plans for a retractable roof were squelched because of the price tag) spun into an asset. “So God could watch his favorite team,” one player famously put it.

As the drums of the live band started to pound, the seven cheerleaders burst from that tunnel. “And all of a sudden, we heard noise from the fans, and we’re going, like, ‘What’s going on?’ ” Baker told me in her honeyed twang. Texas Stadium erupted in a joyful noise she can still hear, fifty years later. “And they’re pointing at us. We didn’t know that we had introduced something new to football.”

What they introduced was sex and glamour into the gladiator arena of modern sports. They launched a wave of imitations across the NFL, creating a blueprint for beauty that’s practically branded on the cultural imagination.

It was a watershed year for women, a time when the forces of freedom were starting to be unleashed but also clash. Roe v. Wade was making its way from a Dallas courthouse through the Supreme Court, where it would ignite a battle that’s still raging. It was the year Deep Throat hit American theaters, launching a vogue for “porno chic.” And it was the year Title IX passed, opening the door for women in athletics.

The Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders were a watershed too, combining the precision of the East Texas drill team the Kilgore Rangerettes with the class of the Radio City Rockettes and adding a dose of old-fashioned Texas razzle-dazzle. “We’re looking for an all-American, sexy girl,” choreographer Texie Waterman once told a local news station, taking a bite out of that word, “sexy.” And this internal contradiction—of being good but also a bit bad, of being innocent but also a bit dangerous—became an essential part of their brand, and their explosion.

To follow the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders over the next half century is to watch the pop sexualization of women: on television, on billboards and magazine covers, in swimsuit calendars that became making-of DVDs that became a reality TV show. Though their spot in culture is singular, their struggles and triumphs speak to women’s rising place in the world: how we look, how we behave, who and what determines our value.

These days, they’re seen as a legacy, a throwback to another era. Their instantly recognizable uniform was donated to the Smithsonian in 2018, a piece of American lore alongside Dorothy’s slippers and Abraham Lincoln’s top hat. But the squad has also slipped from its pedestal. Across the NFL, the past decade has brought fair-wage lawsuits, sexual harassment claims, and bad press. Professional cheerleaders for other teams are moving away from sexy sideline dancing, adopting more-modest uniforms, and adding men to their squads. The Carolina Panthers recently brought on the first openly trans cheerleader. (Whether fans want these changes is another matter.)

In February, scandal hit the Dallas Cowboys when ESPN broke the story that the team’s number one PR guy, Richard Dalrymple, had been accused of using his phone to film four cheerleaders in their dressing room back in 2015, resulting in a $2.4 million settlement. The company line had always been that the cheerleaders were protected. The extensive rules that had been put in place decades earlier—dictating everything from how the cheerleaders dressed to the way they conducted themselves off the field—were supposedly for their own good, meant to guard their safety as well as their image. Yet here was the team’s own PR guy being accused of creating a PR disaster. For a squad that prided themselves on “wholesome sexiness,” this was seedy indeed.

The Cowboys and Dalrymple denied any wrongdoing. But my phone blew up with cheerleaders I’d gotten to know during the year I spent interviewing them for the Texas Monthly podcast America’s Girls. How had this happened? Had it happened other times? On sports radio and Twitter and in casual conversation, I heard questions that had dogged me since I’d started this project: Did the world still need professional cheerleaders? Did we ever?

Cowboys’ history books won’t tell you the true origin story of the cheerleaders. “The Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders began as the creation of one man: Texas E. Schramm,” reads a 1984 tome on the Cowboys. Nope, try again. General manager Tex Schramm, who helped launch the franchise, in 1960, was a visionary, a former CBS executive who saw that the future of professional sports was television. And it’s true he kept the squad alive during the years when born-again coach Tom Landry wanted them gone. But the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders are actually the creation of a few women, whose innovative ideas and contributions have mostly been forgotten.

Dee Brock was a woman of the world when the world could be quite small for women. She got her PhD in literature at the University of North Texas after marrying longtime Dallas Times Herald columnist Bob Brock, with whom she had three sons. She taught high school English, though she’d later become a founding faculty member at the city’s first community college, El Centro. She was uncommonly beautiful—blond and five feet seven—and she modeled on the side. She also had a sense of humor. “I don’t really like girls that have that much breast,” Brock remembered legendary clothier Stanley Marcus once telling her as she prepped for a Neiman Marcus fashion show. “Well, I’m sorry,” she replied. “But there they are.”

Sometime before the Cowboys’ second season, in 1961, Schramm tapped her for a Big Idea: beautiful models on the sidelines. Respectfully, Brock told him this dog wouldn’t hunt. Models didn’t move much, and they required money, something Schramm didn’t like to spend. She hatched a different plan. Recruit local high school girls. Pay them with a couple of tickets to the game, give them some kerchiefs and pom-poms. It’s free! Schramm placed her in charge, and she spent the next decade trying to make this formula work, though it ultimately did not. She recruited teenage boys for an experiment in coed cheerleading remembered mostly for its dumb name: the Cowbelles and Beaux.

“That is one of my embarrassing moments,” Brock, now in her early nineties, told me at her home in Tyler. The name was a PR guy’s stunt, and, sadly, it stuck. “My teams were strong. They were not Belles and Beaux.” She practically spat that last part.

Brock had long been a woman ahead of her time. She integrated the squad in 1965, with the help of a local Black teacher named Frances Roberson. The Cowboys had several Black players by then, but much of Dallas was still segregated. In 1971, half of the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders were Black.

The following year, a skimpier uniform, an age bump, and an open audition marked the start of a brave new era. “I think we need an older group of girls,” Brock remembers telling Schramm.

“Old?” He was not convinced.

Older, she explained. Eighteen and above. “And I wanted them to have a sexier costume,” she said.

She didn’t use that word with Schramm, but it was on her mind. Back in the fifties, Brock had landed a spot as a “bathing beauty” in a Dallas summer musical, where she turned heads as one of only two women audacious enough to wear a bikini. That revealing number made her a celebrity in local modeling circles. She wanted her cheerleaders to get that same kind of attention. She also wanted the cheerleaders to be dancers. To put on a show. And she knew exactly who to hire in order to do that: the other woman bold enough to wear a bikini in that summer musical.

Texie Waterman was a petite pistol of a redhead who kept a cigarette forever smoldering between her fingers. She was also the go-to dance instructor in Dallas. “When they told me they wanted dancing cheerleaders, I told them they were crazy,” Waterman said, according to the 1982 book A Decade of Dreams, still the only history of the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders ever published, though it’s long been out of print.

Waterman grew up in Dallas and was a Highland Park High School grad who began teaching dance at seventeen. In her twenties, she had a run in New York City, where she performed in lavish supper clubs like the Copacabana. By the time Brock approached her, she was managing a studio along with her mother. (A very Texas detail: Her mom was also named Texie.) She wasn’t sold on the idea at first. “There’s no stage, no light, no illusion,” she said in A Decade of Dreams. But she went for it anyway, introducing a sexy and playful style of dance that would go on to shape stadium entertainment.

Her initial annual salary was $300. Actually, Schramm didn’t want to pay her at all, but Brock wasn’t about to ask the choreographer to work for free, so she split her own salary, which was $600 at the time. So there you go: $300 a year to build a legendary squad.

“When they told me they wanted dancing cheerleaders, I told them they were crazy,” Texie Waterman said.

The appalling compensation for the women behind the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders is a reflection of both the times and a team known for being cheap. The Cowboys didn’t become all-powerful by giving anything away. That new squad of cheerleaders that burst out of the tunnel in 1972? They got $15 a game, $14.12 after taxes.

“It was enough to fill up my gas tank and buy me a Slurpee,” Baker said. The money was a joke, but it made sense at the start. The cheerleading gig was only a side hustle, but it brought status, sisterhood, the chance to be part of something bigger.

The Original Seven quickly became local sweethearts. Fans started lining up after games to get their autographs. Little girls, little boys, adult men who had never before shown much interest in the action on the sidelines. More cheerleaders were soon added, because 7 wasn’t nearly enough to meet crowd demand. First 15, then 21. They appeared at car dealerships and got their picture in the paper, like hometown pageant queens. It was, in those initial years, a low-key kind of celebrity.

But the cheerleaders were about to go global.

It was November 10, 1975, and the Cowboys were squaring off against the Kansas City Chiefs on Monday Night Football. At the time, the weekly ABC broadcast was a blockbuster, with tens of millions training their eyes on the same game. Three years had passed since the cheerleaders’ debut, and still no other team in professional sports had a squad like Dallas’s. And on this night, the cameras didn’t let you forget. They kept cutting away to those lovely lasses, sipping a cup of water, smiling and laughing on the sidelines.

Then came the moment: A cheerleader named Gwenda Swearengin is shaking her pom-poms overhead as she faces the field between plays. She’s a former Miss Corsicana first runner-up, her long brown hair cascading across both shoulders, and the camera zooms in so tight on her that the white swish of her poms is barely visible at the top of the screen. As the shot lingers, she does something no cheerleader has ever done. She looks straight into the camera—and winks.

“I think she was doing that for you, Frank,” host Howard Cosell cracks to his cohost, Frank Gifford.

“She was very effective,” Gifford responds.

Coy but flirtatious. The perfect tease. One beautiful woman shining her light on every viewer in their living room recliner.

“The wink” became a part of Cowboys mythology, a way to explain the squad’s rocket ride over the next years, and like many myths, it’s about half-true. The moment was a bold breaking of the fourth wall—the cheerleaders had mostly ignored the cameras before then. And that game ramped up their profile, as did their appearance two months later on the sidelines of the 1976 Super Bowl. But even before the wink, the cheerleaders were already a fixture of an enterprise that was casually turning everyday sports fans into armchair voyeurs—not in a single moment, but over a season of televised games.

Football’s exploding popularity through the seventies had a lot to do with TV sets moving to the center of American households. The cheerleaders went along for the ride. Waterman had designed the squad to play to enormous stadiums, where their exaggerated movements could be seen high in the bleachers, but television collapsed the distance, with close-ups that were startling in their intimacy, almost as if the cheerleaders were performing in your living room too.

“Honey shots” was the industry term for these cutaways, the invention of a former Dallas TV guy turned ABC sports director, Andy Sidaris. “I got the idea for honey shots,” he said in the 1976 documentary Seconds to Play, “because I am a dirty old man.”

That same year, Dee Brock left the cheerleaders. She eventually landed a gig as a senior vice president at the Public Broadcasting Service, where she developed educational programming. Waterman stayed on, but the demand created by the massive TV exposure was proving too much for one person. And so Schramm asked his secretary, Suzanne Mitchell, to run the cheerleaders “in your spare time,” a diversion that would soon take over her life.

As the story goes, when Schramm first interviewed her for the job of secretary, Mitchell was back in Dallas after a stint in New York City, where she’d worked in publishing. He asked where she saw herself in five years. “Your chair looks pretty comfortable,” she told him. He hired her on the spot. She would soon transform an upstart group of pretty sideline dancers into a sleek media machine.

She ruled by fear and never pretended otherwise. Full hair and makeup had to be done for rehearsal. No appearing in uniform around alcohol. No chewing gum. The cheerleaders had always had rules. “No fraternizing with players” was gospel from day one, an attempt to keep players from distraction (and the wives from mutiny). But Mitchell was the daughter of a military man, and she introduced a boot-camp mentality, making the rules a way of life. Scales showed up in the studio. Cheerleaders were rebuilt in a new image, like soldiers enlisted in the army of glam. She expanded the squad, ultimately settling on 36, and fashioned a sort of seventies Spice Girls: there was the sporty one, the sweetheart, the beauty queen. The idea was that every little girl would see herself—and every man would see his fantasy.

In 1977 the cheerleaders landed on the cover of Esquire, one of the most sophisticated and influential titles in the heyday of magazines. “The Best Thing About the Dallas Cowboys,” it read. A cheerleader named Debbie Wagener, a dead ringer for Blondie’s Debbie Harry, stands with her hands on her hips. The Cowboys merchandising arm got cranking soon after that: there were cheerleaders calendars, playing cards, Frisbees, even a toy van.

Annual auditions ballooned to more than a thousand hopefuls by 1978, with swarms of gorgeous, talented women all competing for the same 36 spots. “You can be replaced in a second,” Mitchell used to tell anyone who stepped out of line, though most didn’t. These women weren’t going to jeopardize their first taste of fame.

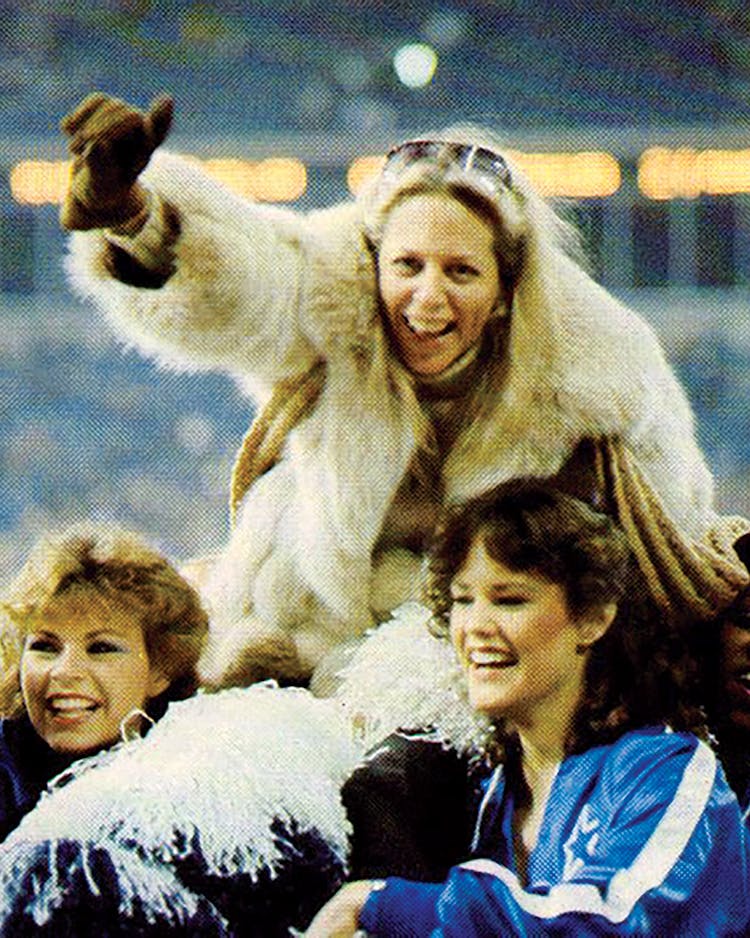

“We were put on a pedestal,” said Shannon Baker Werthmann, who joined the squad in 1976. “You did have to pinch yourself.” Through the late seventies, her Farrah Fawcett hair and killer high kicks made her a poster girl and the cheerleader who always seemed to get the most fan mail. It’s easy to forget how young these women were as they blasted into the zeitgeist. Werthmann was seventeen when she first tried out for the cheerleaders. The rule was you had to be eighteen, but she didn’t want to wait, so she lied on her application.

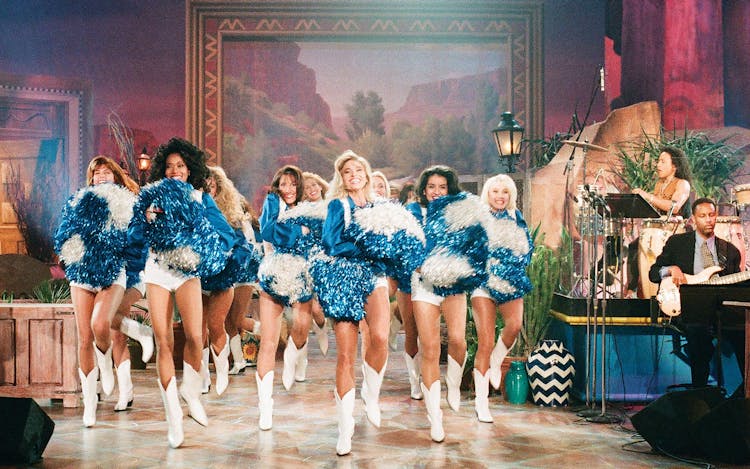

In 1978 the squad was flown to Utah for its first big TV spot, a special hosted by the Osmond Brothers. “We were treated like princesses,” Werthmann told me. “We rode in limos. There was a large spread of food waiting for us.” This was the dream. They even toured Donny and Marie’s home. Marie, a teenager at the time, had a pink bedspread and a collection of dolls, a detail that stuck with Werthmann. “She was a girl, just like us.”

Tami Barber was there too. The only child of a Cowboys diehard, Barber came from a small Nebraska town and had made the squad in 1977, at nineteen. Suddenly, she became known as “the one with the pigtails” and found herself signing autographs. She recalled appearing on Jerry Lewis telethons in Las Vegas. “I got to see Johnny Carson and Frank Sinatra and Dionne Warwick,” she said. “I mean, I was the fan at that point.”

But these events stood in stark contrast to the reality for many at home. The cheerleaders never got a slice of the merchandising profit, and the $15-a-game pay wouldn’t budge until the nineties. Rehearsals could be as frequent as five nights a week, sometimes lasting till midnight, in an un-air-conditioned studio meant to prep them for the Texas heat. Many of them were broke, hustling to make rent, falling asleep at their desks during work or school. Wagener was a checker at Tom Thumb when she appeared on that Esquire cover—ringing up the glossy magazine she graced and quietly putting it in someone’s bag.

In 1977 the cheerleaders released their own poster: five glamazons lit by neon, with smoke billowing around their ankles. At the center was a brunette named Suzie Holub, her eyes smoldering as she looked directly into the lens. “Damn if that ain’t a come-hither look,” Tex Schramm told photographer Bob Shaw when he saw the image, a shot that would sell around a million copies and turn the cheerleaders into the country’s hottest pinups. But this popularity came with a dark side.

That year, after a performance in Wichita, Kansas, the cheerleaders were walking back to their bus when fans descended on them in a way they never had before. “A couple of girls started running, then we started running, and then the crowd was running,” Tami Barber remembered. “It was our Beatles moment. We were running for our lives because these people were grabbing at us.” Barber sat inside the bus as strangers pounded the sides. “My heart was beating so fast, and it was the first time I thought, ‘Why are people crazy? We’re just us.’ ”

The visibility brought threats even Suzanne Mitchell couldn’t manage. One night, Barber picked up the phone in the apartment where she lived alone. “Good-night, Tami,” said an unfamiliar man’s voice. She hung up, but he called back another night, and she was so scared she moved. She wasn’t the only one. “You’ll have to have an unlisted number,” Mitchell instructed the cheerleaders, but often that wasn’t enough. A cheerleader named Billie Mitchell once opened her eyes in the middle of the night to find a strange man standing beside her bed. She chased him out, and then she moved too.

The Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders had become a bona fide global sensation. They starred in a hit 1979 made-for-TV movie; they became part of the story arc in a two-part episode of The Love Boat; they faced off against some Cowboys football players on Family Feud. And along the way, Mitchell had the impossible task of managing these internal contradictions: she had to keep the cheerleaders safe while presenting them as endlessly available; she touted their singularity in public while quashing their egos in private. She had to control this wildfire at the same time she fanned the flames.

Cheerleaders across the NFL started copying the Cowboys, with more than twenty squads transforming seemingly overnight into sexpot dancers. Sports Illustrated called it “the Great Cheerleading War of 1978.” The Cowboys had become the most visible and most valuable franchise in the NFL, and a huge part of the brand was these fetching women. It was a match made in marketing heaven: in the center of the field, Captain America Roger Staubach, and on the sidelines, 36 Miss Americas in a famously tarty uniform.

The year 1978 was also when an adult film actress by the name of Bambi Woods donned that glorious uniform (or at least an imitation of it) in a less-than-glorious scene. Debbie Does Dallas was a shoestring porno film whose plot, so to speak, followed a young woman with the dream of cheering for a certain legendary Dallas football team. The marquee outside the New York City theater where it debuted falsely claimed that Woods was an “ex–Dallas Cowgirl cheerleader,” and the Cowboys—presumably incensed that the “wholesome sexiness” they’d pioneered had gone full frontal—sued for trademark infringement, resulting in the deliciously named lawsuit Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders v. Pussycat Cinema. Newspapers and TV stations devoured this saga. The Cowboys eventually won the case. But the media frenzy turned a fly-by-night skin flick into a blockbuster.

In turn, the cheerleaders doubled down on their wholesome image. They launched a line of children’s clothing that included a little satin jacket and developed a new logo of a doe-eyed cartoon girl dressed as a cheerleader and looking all of seven. Young girls had by then become a major fan base for the cheerleaders. But the sexual tease the squad had introduced was tricky to put back in the bottle.

That same fall of 1978, five women dressed as cheerleaders posed for a feature in Playboy. The group was a rogue outfit called the Texas Cowgirls, a rival Dallas-based agency formed by women who had quit the Cheerleaders (fed up with the rules, worn down by the demanding schedule and low pay) or been nixed from the squad as auditions became cutthroat. The Cowgirls made appearances at places where the cheerleaders wouldn’t dare to go, often events where alcohol was served. And their fees were shared evenly among the members, unlike the cheerleaders, whose occasional appearance fees went to a select group of favorite members of the squad, and who did not see a dime from the squad’s numerous merchandising deals.

The Texas Cowgirls’ splashy debut in Playboy was a riff on the Cheerleaders’ top-selling 1977 poster, five glamazons in triangle formation, except for one detail. This time, their tops were untied.

Despite the controversies of the late seventies, the cheerleaders rarely encountered any sort of public backlash. But in 1982, they arrived at Fresno State University, in California, to rehearse for a halftime performance, and as they entered the campus they were greeted by a big white bedsheet hanging out the window of a building, spray-painted with the words “Hearts and Minds, Not Bumps and Grinds.”

The cheerleaders had transformed culture in the previous decade, but so had second-wave feminism. Ms. magazine debuted the same year, 1972, as that iconic uniform did, and the consciousness-raising publication cofounded by Gloria Steinem had helped popularize ideas about sexual objectification and the male gaze during a decade when legal victories like Roe v. Wade and the 1974 Equal Credit Opportunity Act were changing women’s lives. By 1982, a feminist vernacular had seeped into the American vocabulary in the same way hot pants and jiggle had seeped into network programming, and on the sidelines of Fresno State, those two forces were about to collide.

The drumbeat of protest had been building all week. A professor in the physical education department named Rhita Flake started a petition, swiftly picked up by the news media, calling the cheerleaders “demeaning to women” because their primary function was “to provide sexually suggestive entertainment for male sports fans.”

“Sex objects”—that was the slur that followed the squad, even if the cheerleaders, and many fans, saw themselves as more: role models, goodwill ambassadors, talented performers. In 1979 they’d even begun doing USO tours to visit soldiers in Korea and elsewhere overseas. So when director Suzanne Mitchell heard about Flake’s comment, she shot back in the press, “The first thing I’d like to ask her is, what has she ever done for her country? We helicopter into the DMZ.”

Things got ugly at the performance later that day, when protesters gathered outside the stadium. Dana Presley Killmer, who joined the squad in 1981, remembers the ominous vibe. “It was so nasty that the faculty at the university had to form a human fence on either side of us so we could get out of the bus and get onto the field without [protesters] throwing rocks.” The confusing part for the cheerleaders was that the appearance was a charity event to raise money for the college’s athletics department. But in the heated battle of the sexes, the cheerleaders were now deemed to be on the wrong side.

The cheerleaders may have been thought of as eye candy for men, but they had become a lightning rod for many women, and still are to this day. Their popularity raised complicated questions about women’s beauty and sexuality—how do you extol those qualities without being defined by them? “Exploitation” is a word that often gets thrown around by critics of the cheerleaders. But who decides that these women are being exploited if they say they’re not?

“We really were doing what we wanted to do,” Killmer told me from her home in East Texas. “No one forced me to be a Dallas Cowboy cheerleader.” Quite the opposite—she beat out more than two thousand women for her spot.

By the end of the decade, the cheerleaders’ tightly calibrated mixture of sweetness and licentiousness was about to face an entirely different challenge—the team’s new owner.

One Saturday in early 1989, Mitchell’s assistant, Debbie Bond Hansen, arrived at the office to discover all sorts of unfamiliar men wandering the halls, shuffling through papers. “There were all these suits,” remembered Hansen. She called Mitchell, who was at home. What was happening? The evening news would tell them soon enough. An Arkansas oilman named Jerry Jones had bought the Dallas Cowboys. A new sheriff was in town.

Hansen had been with the cheerleaders since 1979. Through much of the following decade, she’d proven a trusty second lieutenant to Mitchell. Once, after hearing a rumor that one hopeful was moonlighting as a stripper, Mitchell dispatched her to visit every strip club in Dallas. “I had never been to a strip club, okay?” said Hansen. “I was hiding in the corner because I didn’t want anybody to recognize me.” She slunk around in oversized sunglasses and a fur coat. Since her last name at the time was Bond, this detective work earned her the nickname “Double-Oh-Seven.”

Mitchell and Hansen had steered the cheerleaders out of the scandalous late seventies and the feminist pushback of the early eighties by leaning on the rules. The rules were used to keep things steady and predictable, but they also offered instruction in a certain kind of Southern womanhood. “A lot of people don’t know this—we were a grooming school too,” Hansen told me. The matter of when to wear heels and what fork to use with the salad might seem like trivial concerns, but those questions could be overwhelming to small-town women hoping to be something more. The ultimate goal of each cheerleader was made clear in Mitchell’s photocopied handouts, which were given to rookies: “A girl becomes a LADY.”

Jerry Jones didn’t seem to be a fan of rules—not theirs, anyway. He fired Coach Landry. He shunted Tex Schramm to the side till the legendary manager walked off the field he’d built, and the ever-loyal Mitchell quit soon after. “They were America’s Team,” she told a reporter after she resigned. “[Now] they’re Jerry Jones’s team.”

Mitchell installed Hansen as her successor, but the scene had changed in distressing ways. “I’d be having a rehearsal in the dance studio, and Jerry Jones would come down with his friends and his cocktails,” Hansen said. Prior to this, the cheerleaders had always been strictly siloed. They entered and exited through different doors than the players did and often only saw them on the field. Under Jones, the girls’ school vibe had turned strip club. There was the owner, “clinking the ice, watching the girls rehearse,” Hansen remembered. “I was just like, ‘Gosh, this is not like the old days.’ ”

According to Hansen, Jones brought her into his office and explained he was relaxing the rules. Let the cheerleaders date players, let them appear around alcohol. Who cares? He also wanted to change the uniform. At least that’s what Hansen told reporters who ambushed her at the office a few days later. On the news clip, she speaks in a solemn voice as microphones cluster near her chin. “I have received pressure from within the front office to add to the cheerleaders’ uniform during the summer months biking pants and halter tops.” She tells reporters how this Jones character responded to her objection that cheerleaders should not be seen in untoward scenarios. He told her, “Debbie, alcohol is here to stay.”

Hansen resigned, and she wasn’t the only one. Fourteen cheerleaders quit, although Jones sweet-talked them back, saying it was all a misunderstanding. He brought in his Stanford-educated daughter, Charlotte, to help straighten out his PR mess, and in time she’d become president of the cheerleaders and a major power player in the Jones family business.

This particular standoff evokes a tension that has existed in women’s lives for generations. The old regime wanted to protect the women, but the strict rules also constrained their behavior—and placed all responsibility exclusively on the women’s shoulders. Cheerleaders were kicked off for dating players, who never suffered a thing. Cheerleaders were kicked off for much less, in fact—drinking in uniform, wearing a salty Halloween costume, any behavior deemed unladylike. Suddenly, a new regime wanted to loosen the corset, granting the women more leeway—but to do what? One cheerleader, a two-year veteran named Cindy Villarreal, said she quit after getting an unusual request to appear with another cheerleader on Jerry Jones’s private jet. (The Cowboys organization declined several interview requests. A spokesperson for the team disputed Hansen’s and Villarreal’s accounts but offered no details.)

It was, indeed, Jones’s team now. And over the next decades that team would nab three Super Bowl championships, garner a heap of tabloid scandal, and become the most lucrative brand name in sports, valued at more than $6 billion.

We really wanted this year’s calendar to be special,” cheerleaders director Kelli Finglass tells an ESPN film crew on a windswept Caribbean beach in 1999. “We wanted it to be classy and elegant and to expose the cheerleaders as the premier group of women in all sports.”

“Expose the cheerleaders”—was that a cheeky joke or a slip of the tongue? The swimsuit calendars, first released in the early nineties, certainly did expose those cheerleaders: over time, the bikinis got smaller, the poses more risqué. The women were busy keeping pace with a culture gone wild. The nineties saw the rise of Victoria’s Secret Angels and MTV Spring Break, all of which amounted to a lot of soft-core porn on cable channels just as real porn started running rampant on the internet. It was now mundane to see a nearly naked woman rolling in sand in a commercial for watches, for cologne—for anything, really.

Finglass had been a Dallas Cowboys cheerleader from 1984 to 1988, when her last name was McGonagill. Raised in the small East Texas town of Lindale, she was known for her outgoing personality and radiant smile. She’d studied marketing in college, and Jones eventually hired Finglass as the new director in 1991. She turned out to share her boss’s marketing prowess and knack for corporate partnerships. Every last detail on those cheerleaders got a sponsor, from their Lucchese boots to their visits to Planet Tan.

The swimsuit calendars became a fixture of display tables at Barnes & Noble, next to Sports Illustrated pinups and Far Side desk calendars. Their reach was extended even further when ESPN decided to film those making-of-the-swimsuit-calendar specials, hoping to fill up programming on an expanding cable network. It was one long hour of behind-the-scenes moments: cheerleaders getting their makeup done, cheerleaders posing beside rocks as waves crash against them, all set to tropical club music. A few years later, the Cowboys produced their own swimsuit special, which they sold on DVD.

But in 2006, the cheerleaders’ exposure hit a new level: they got their own reality show. Making the Team was the brainchild of writer-producer Eugene Pack, whose many credits included the Miss USA Pageant. This was high tide for reality TV, a genre that exploded around the turn of the century with Survivor, Dancing With the Stars, and American Idol, shows that allowed viewers to pass judgment from the comfort of their couches. Like those hits, Making the Team followed the audition process each year, as the judges—led by the ever-poised Finglass—whittled down hundreds of hopefuls. The show had built-in dramatic tension: only 36 women would (metaphorically) survive. Thrilling competition, tearful eliminations, and plot twists drawn from real life (injuries, heartbreaks, personal tragedies) became a part of the narrative.

Unlike shows such as The Real Housewives, Making the Team did not traffic in catfights, and it felt earnest in a way that swept you up into these women’s hopes and dreams. Whether or not the producers were scheming behind the scenes to drum up ratings (I was told by several crew members they weren’t), the women who made the cut seemed chosen because they were the best candidates, not because they would instigate drama. Although early seasons included a certain mean-girl snideness and casual body-shaming endemic to the era, the show started to move away from that. Perhaps the most surprising thing about Making the Team—given all the cleavage, hip thrusting, and hair flicking—was how endearing it could be.

“I used to watch that when I was stoned in college with my friend Suzy,” New Yorker writer Jia Tolentino, who grew up in Houston, told me. “It was the kind of thing where we thought we might be watching it in a snarky, we-will-laugh-at-these-people way, and then we were like, ‘I would f—ing die for these women.’ ”

Tucked away on a cable channel called CMT (Country Music Television), it was ignored by most media even as it caught on with a hard-core fan base of women, many of whom might never set foot inside a football stadium. If honey shots had reduced the cheerleaders to cutaway sex objects, the reality show expanded them into bona fide talents. Dance became the central theme, from the opening cattle call, when groups performed a number in front of a panel of judges, to the long studio practices, as newbies struggled to perfect their high kicks and jump splits. The most entertaining segments were the solo performances, when the women revealed a finesse for pirouettes and grand jetés that seemed to surprise even them. Early seasons had an American Idol–style tendency to mock less talented performers, and the threat of reality show cameras may have tanked the audition numbers, leading fewer hopefuls to try out, but the women who did show up were top-notch. Making the Team became one of the longest-running and most popular reality series in CMT’s history, and it turned women who’d long been anonymous into characters whose journey viewers could follow through the seasons.

But another reality was emerging alongside the show, and this one didn’t get airtime. In 2014 two Oakland Raiders cheerleaders filed a class-action suit against their squad, claiming wage violations. The lawsuit ended in a $1.25 million settlement for the cheerleaders and launched a wave of litigation across the NFL. For decades, low pay had been industry standard, and some even argued that this was a good thing. “You get a better quality of girls who aren’t doing it for the money but for the love of dance,” Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders choreographer Judy Trammell told a reporter from E! News back in 1996, when the pay rate was still $15 a game.

A new generation of young women, steeped in social media activism, were revealing this tradition to be something else entirely: against the law. Similar suits followed with the Cincinnati Bengals, New York Jets, and Buffalo Bills, while ones that cited body-shaming and discrimination hit the Houston Texans and the New Orleans Saints, respectively. A chill shot through the NFL.

So much of what had made it possible for the Cowboys cheerleaders to become a global phenomenon—the armchair voyeurism, the throwaway pay, the strict weight requirements ensuring a supposedly ideal body, one that could be dissected by cameras—began crashing into conflict with the #MeToo era, as treatment of women took center stage. Squads started wearing more-modest costumes, adding men, trading hip thrusts for the kinds of stunting seen on Netflix’s Cheer, moves that were less “all-American, sexy girls” and more Cirque du Soleil.

In 2018 the Cowboys were hit with a lawsuit too. Erica Wilkins had been a star on the squad who appeared on the cover of a Cowboys Star magazine swimsuit issue in 2016. It was her most lucrative year, and, according to her complaint, she raked in a total of about $16,500, including game day and appearance fees. The most damning detail found in the complaint was that Rowdy, the team’s mascot, made about $65,000 per year during that same period.

Though Wilkins filed the suit as a collective action, no other cheerleaders joined her. High-profile veterans, including Real Housewives of Dallas star Brandi Redmond, instead circled the wagons on social media. “I would do it all over again for free,” she wrote, a common sentiment among cheerleaders but one that isn’t actually relevant to the legality of a contract. According to Wilkins’s suit, the Cowboys classified their cheerleaders as employees, but they weren’t making minimum wage. They received $200 for game day and $8 an hour for rehearsals. The seventies girls may have died for that kind of scratch. But even with the pay bump, Wilkins said, her pay often fell far below minimum wage once she logged all the hours. She settled her suit out of court, and while no cheerleaders ever joined her, it benefited them anyway. Game day pay reportedly doubled to $400.

Meanwhile, much of the media, which had once treated cheerleading as the ultimate fantasy, started to treat it more like a waking nightmare. “A Ponzi scheme in hot pants,” read a piece on Deadspin. “So, Uh, Why Does the NFL Have Cheerleaders Again?” asked the Ringer. What was once new and sexy now looked outdated and sexist. And yet, each May, hundreds still vied for the honor.

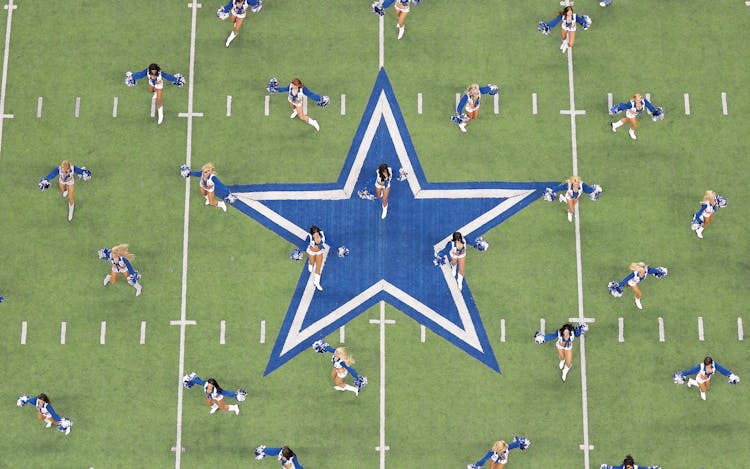

Last November, the cheerleaders performed a sixtieth anniversary halftime show at AT&T Stadium, a.k.a. Jerry World (it replaced Texas Stadium in 2009), where the Miller Lite and Pepsi logos were displayed right below the American flag. The number sixty actually came as a bit of a surprise. For a long time, the cheerleaders dated their inception to 1972, when the uniform debuted. But now they were dating it back to the very beginning, 1961, the year Dee Brock started the squad.

I bought a cheap standing-room-only seat in the rafters and jockeyed for a better view as cheerleaders from each decade—white-haired ladies from the seventies, followed by long-haired ladies from the eighties, followed by even more long-haired women from the nineties—took the field for a choreographed routine, one danceable hit after another. And then all of them took the field together for the finale, “We Are Family,” by Sister Sledge.

The Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders have always been a family. At least, that’s what people I interview tell me. And so the scandal that erupted in February was more than just an alleged transgression. Because the offense was coming from inside the house.

PR maven Rich Dalrymple had unexpectedly retired earlier that month. He was greeted with hosannas from local sports journalists, who didn’t seem to notice that for the organization to quietly disappear one of Jerry Jones’s top advisers without so much as an announcement on their website was very weird. Weeks later, veteran investigative reporter Don Van Natta Jr. broke the story on ESPN. Dalrymple had been accused of secretly filming as four cheerleaders changed in their dressing room.

It was shocking, but not surprising. During a 2001 postgame show for a playoff matchup hosted by the Philadelphia Eagles, a sportscaster revealed that visiting players, whose locker room was adjacent to that of the Eagles cheerleaders’, were caught peeping at the women as they undressed and showered. A lawsuit followed, with claims that such behavior had been going on for nearly twenty years, that the peepholes were “common knowledge among virtually the entire National Football League,” and that they were “considered one of the special ‘perks’ of being a visiting team of the Eagles.” More recently, the Washington Football Team (now the Commanders) had their own voyeurism scandal after a former executive was accused of having staff create a lewd video that pieced together nip slips and other risqué B-roll footage from their cheerleaders’ swimsuit shoot.

Representatives from the Cowboys claimed that an investigation into the Dalrymple incident, which took place in 2015, revealed no wrongdoing. Yet the team still paid that confidential settlement of $2.4 million. At the time, my podcast on the cheerleaders had just wrapped, and I went on the Dallas sports station the Ticket. One of the questions I’d been pondering was how to protect against toxic voyeurism, when, as I explained on-air, “low-key voyeurism is part of their brand.” I noted that in 2013 fans were invited to pay $6,999 to travel to Mexico and watch the swimsuit calendar shoot in person. Among the listeners that day was Kelli Finglass, who later messaged me on Instagram, where we had occasionally traded direct messages. Kelli had complimented my work on the podcast (though she’d declined to participate), but she wasn’t thrilled with me that afternoon.

“Your comment that the DCC were designed for low key voyeurism made me gasp,” she wrote. I had a momentary stab of guilt, wondering if I’d gotten the story wrong. But I’d often suspected that many of the cheerleaders didn’t fully know their own story, and that modern audiences hadn’t fully absorbed the extent to which we’ve all become voyeurs—watching the grand spectacle through the screens in our living rooms, which became our bedrooms, which became our laptops, which became the phones in our palms.

Cheerleaders began texting me, eager to talk but wary of going on the

record. The team instills fierce loyalty (some might say quaking fear), and it’s unusual to hear cheerleaders openly questioning the organization’s integrity or griping about current leadership, but several were cutting loose that day. “Don’t Tarnish the Star” was a mantra those women had taken to heart. They followed the rules, they toiled for next to nothing—and the people tarnishing the star turned out to be the ones in control all along. “Every decision I’ve made in my life, I thought about that team,” Tami Barber, now 64 and staring down a cancer diagnosis, told me. She was one of the rare few who didn’t mind being quoted. Her heart would always be with the cheerleaders, she said, but the Cowboys? “If I were in AT&T Stadium today, I would puke on the star.”

It became a long, dark off-season for the Cowboys. In March, news broke that Jones had been slapped with a paternity suit by a 25-year-old woman alleging he was her father. (She later dropped the suit.) Later that month, Making the Team was quietly canceled. No reason was given, but it was hard not to speculate either that the scandals had given CMT cold feet or that the cheerleaders, scrambling to control the narrative, felt that reality cameras came with too much risk. The Cowboys kept on as if there were nothing to see here. There was a big NFL draft party outside the team’s Frisco practice facility later that month, with cheerleaders high-kicking and shaking their silver-and-blue pom-poms.

Of course, the franchise has been nothing if not bulletproof. By summer, talking heads were debating when (if?) they’d win the Super Bowl again, and Jones was awarded a bid to host the 2026 FIFA World Cup in his behemoth stadium. The future of the cheerleaders, on the other hand, was less clear.

The cheerleaders changed the world. And the world changes. They burst out of that tunnel and shifted the way we saw sex and beauty, commerce and culture. But as our perspectives shift, so do our heroes. Women don’t want to be on the sidelines anymore. Sexiness in service of men’s sports strikes many as painfully outdated. The erotic contagion the cheerleaders sent through the NFL is heading in the other direction now, with many squads reinventing themselves as coed, more athletic, family-friendly. Can the all-American sexy girls stick around in a landscape that seems to be crumbling? A landscape they helped build? I wouldn’t bet against them.

Still, fifty years is a long time to hold on to tradition. Several of the women who shaped this phenomenon have passed on. Texie Waterman died in 1996, Suzanne Mitchell in 2016. But the original architect is still around.

On a sunny afternoon in early June, a Cowboys bus pulled up alongside a curb in Tyler. Eight current cheerleaders stepped out in summer dresses, followed by a few former cheerleaders in jeans and sparkly Cowboys jerseys. All of them made their way up the sidewalk and into a home whose entryway led to a cozy book-lined room. Sitting in an armchair was Dee Brock, 92 years old but with the same fine bone structure, her long white hair swept to the side in a ponytail. Brock hadn’t been able to attend the sixtieth alumni reunion, so the cheerleaders brought the celebration to her.

“Dee knew how to get people’s attention back in the day,” Finglass said once everyone had gathered inside. And so her gift, she explained, should be similarly eye-catching. She pulled out a lifetime achievement award, a white leather football studded with rhinestones that caught the light when Brock turned the ball in her hands, before gamely tucking it under her left arm, as if she were about to run for a touchdown. Her central role had long been forgotten, so it felt like a sign of institutional health that she was being honored, as if the present could shake hands with the past.

The young cheerleaders lingered by Brock’s side all afternoon like long-lost granddaughters, leaning their heads on the chair where she sat, soaking up her wisdom, holding her hand, almost as if they never wanted to let it go. The squad began as only an experiment—but what an experiment it turned out to be.

This article originally appeared in the September 2022 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “A Half Century of High Kicks and Hot Pants.” Subscribe today.

[ad_2]

Source link