Julián Cardona fearlessly roamed the streets with his camera in tow, photographing corpses and listening to wailing survivors as one of the great chroniclers of an undeclared war between cartels and the Mexican military that has cost thousands of lives in Ciudad Juárez, a sprawling, smoggy city that rises up from the Chihuahua Desert just south of El Paso. Some called him the “Bard of Juárez.” He was a fearless sage—a man to whom many confided secrets—and a bold illustrator of butchery and tragedy. To the very end of his life, he watched and he listened, both as a photojournalist and as an author, filling his head and his notebook with astute observations about the methods Juarenses and others along the border used to cope with the violence unfolding around them.

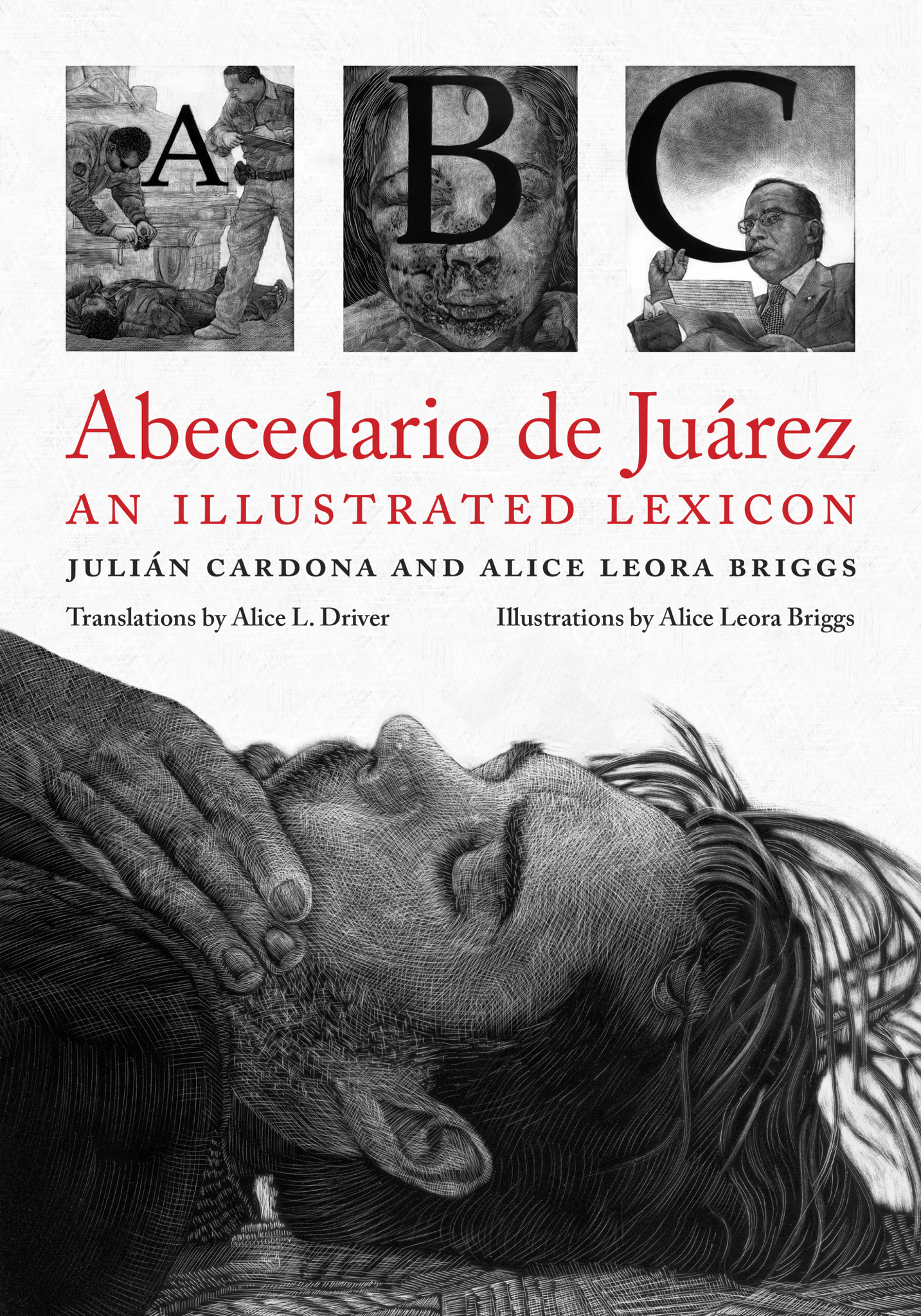

Slowly, without meaning to, Cardona began to assemble a glossary of narcolenguaje—a definitive glossary of terms spawned by the border wars of the 2000s and 2010s. The result is Abecedario de Juárez, Released earlier this month, the book is an unconventional and fully illustrated, alphabetical account of an era in which border citizens in conflict zones used words, shortcuts, and stories to process relentless waves of violence.

Cardona got his start covering crime—or nota roja—as a photographer for El Diario de Juárez and other local media outlets and began collecting stories for this book at least a decade ago. But his work assumed a far more interesting shape after he met a Tucson-based border writer and gifted artist, Alice Leora Briggs, through a mutual friend, another legendary border storyteller named Chuck Bowden.

Many words captured in this book, cowritten by Cardona and Briggs, describe the murdered and the executed, including terms that now commonly appear nationwide in the Mexican press as border violence has spread. Under the letter “A” alone you’ll find: asfixiado (the asphyxiated); acartonado (a desiccated corpse dumped in the desert); ahogado (the drowned); ahorcado (the strangled); acuchillado (a person with single or multiple stab wounds); and acribillado “someone or something “riddled with bullets.” Under E, you’ll see encobijado (a corpse wrapped in a blanket) and encajuelado (a corpse dumped in a trunk.)

Perhaps more telling is the first verb under “A”: abatir. This seemingly mundane term literally means to “fold down” or “bring down.” But the command to abatir, as Cardona and Briggs write, is a euphemism used by the Mexican Army to disguise particularly ruthless mass executions. The word “calls to mind countless Juárez kidnappings, executions and massacres in the dark of night or in the gray hours near dawn,” the authors write. Such observations about the way words have been misused and construed to hide ugly realities resonate strongly throughout this book.

Cardona and Briggs’s relationship was based in part on trust built by their previous collaborations with mutual friend Bowden. In a more hopeful time, Bowden and Cardona both contributed to the 1998 book Juarez the Laboratory of our Future, which featured photos by Cardona and essays by Bowden, Noam Chomsky, and Eduardo Galeano. Cardona later provided photojournalism for Bowden’s 2008 book, Exodus/Exodo on the mass migration spawned by what was then a new and shocking wave of border violence. Later, Bowden collaborated with Briggs, a gifted artist and writer and Guggenheim fellow, on the 2010 book, Dreamland: The Way Out of Juárez before Bowden’s death in August 2014.

Bowden’s introduction spawned a new collaboration between his friends. Cardona had been scribbling away and Briggs had already built an impressive collection of border illustrations. Working together, they created a moving melange of observations and illustrations of life and death on the border that make the experience of reading Abecedario something like visiting an important exhibit at an art museum.

At the head of each of their alphabetical list of terms is a richly drawn letter with one of Briggs’ detailed drawings. For the letter “E,” she drew a soldier walking an attack dog above the definition of the slang term “Efecto cucaracha” (literally, the cockroach effect), a term invented by the Mexican government to portray the military and federal police as successful forces in the war on drugs by scattering criminals as if they were bugs after crackdowns. Instead, they write there’s no evidence that criminals truly avoid the military; instead, there’s more documentation of how military and federal police cut deals and collaborate with criminals.

By 2020, Cardona and Briggs had essentially finished their collective illustrated portrait of Juárez in crisis. They’d reached “Z” for Zetas, a group named for the letter itself that is perhaps the most notorious of all border cartels. It’s defined both as “a crime syndicate considered by the US government to be the most technologically advanced, sophisticated and dangerous organization in Mexico” and as a group formed by fourteen Mexican Army officers and soldiers who’d been trained by the elite School of the Americas and then deserted.

But before their book could be published, Cardona fell and died in the street in September 2020, the victim of a distressingly public death blamed on natural causes. That death came before his last publishing contract was signed—and nearly 18 months before this book would finally emerge into the world. It was a tragedy that in some ways echoed all of the deaths that Cardona himself had documented in the last years of his life.

Briggs mourned his passing. Yet enough of the work was done that she knew she could finish without him. (Translator Alice L Driver contributed and another gifted collector and another author and chronicler of border life, Howard Campbell, supplied the introduction).

This is not a book to be read in a single sitting. It’s at once a history book, a reference book, and an indictment of the militarization of the border by the Mexican government and of the government’s continuing failure to end enduring violence.

It’s also a kind of homage to Julian Cardona: Woven between weird words and unconventional definitions are many of Cardona’s observations. Some entries sound like the stories he might once have told over drinks at a bar, or while walking down the street. Or in a visit to the cafe near where he died. They have the flavor of shared secrets or of stolen moments.

This book is often hard to read. And yet there’s magic here too: In some ways, Cardona returns to life on these richly illustrated pages. In more than one place, Briggs includes a detailed portrait of Cardona. In her favorite, she caught him gazing into the middle distance with his mouth open in the middle of telling a story.