Imagine if you were on the top of the world. You had achieved greatness; you had persevered to do something no one else had ever done.

You were a hero to tens of millions and known around the world. Everything you did was news; every choice you made was scrutinized.

You had endured a trial by fire that few others could conceive of, never mind survive and surmount.

Imagine if you were Jack Roosevelt Robinson in October 1947. After shattering the more than six-decade-old color barrier in what was then narrowly defined as the “Major Leagues,” after enthralling the baseball world with millions cheering you on and millions booing you, after leading your Dodgers to the National League pennant, after almost upsetting the mighty New York Yankees in the ’47 World Series, you deserved a rest.

Robinson’s Dodgers finally succumbed to the Yankees in Game 7 on October 6, 1947, ending a long season that was among the most significant in American sports history. New York had won its third world championship in the decade and would go on to win a fourth two years later when the Bronx Bombers began a string of five consecutive Fall Classic triumphs from 1949 to 1953.

However, hard as it is to believe now, Jackie Robinson was grossly underpaid that year. For all his other virtues, Brooklyn general manager Branch Rickey was famous — his players would probably have preferred infamous — for being a tightwad in salary negotiations. Rickey squeezed the club’s money so tight you could hear the eagles on the greenbacks scream.

For risking his life off the field and risking his sanity on the field, Robinson’s salary was only $5,000 — less than $61,000 today — though that figure was augmented by his $4,000 share of Brooklyn’s World Series players’ pool.

How to beat the high cost of living

Given the expense of living in New York City, Robinson’s paltry salary was inadequate to support his wife Rachel and their young child. To supplement his salary, Robinson agreed to be represented by New York’s General Artists Corporation (GAC), an agency that negotiated endorsement contracts and other opportunities for well-known public figures.

Taking advantage of Jackie Robinson’s heroic image and the intense public interest in his life, GAC organized a series of personal appearances for their superstar client in the offseason, beginning just a few days after the World Series ended. The initial dates on the tour landed Robinson in Detroit.

The Detroit portion of the tour was unusual in several ways. First, it involved Robinson playing baseball, whereas the rest of the tour involved stage appearances variously described as “shows” or “skits” or just “vaudeville.”

Robinson, of course, was simply being paid to be himself and not for his theatrical talent, though his agent had also landed him a well-paying movie deal. The movie project Jackie was to star in had the working title Courage, but it never was made, and Robinson ultimately sued the producer (successfully) for the $14,500 he was to receive.

And the famous Jackie Robinson Story? That movie wasn’t released until 1950 and was unconnected to the failed 1947 project.

Robinson in Detroit

Even more unusual than the idea of Robinson doing vaudeville was the modest venue in which he appeared in Detroit: Dequindre Park. Located two miles north of Hamtramck, where the Detroit Stars had played in the 1930s, Dequindre Park was essentially a sandlot diamond that had been enclosed in 1941. While not quite in the middle of nowhere, it wasn’t conveniently accessible since it wasn’t on a streetcar line. In the 1940s, the Detroit municipal streetcar system was one of the most extensive and efficient in the US, but fans who wanted to attend games at Dequindre Park had to walk, take a bus, or drive, and the park was not in the middle of a densely populated neighborhood. In addition, most African Americans did not own cars.

Clearly, no one would have thought ill of Robinson if he had begged off. He had already turned down a lucrative offer to play basketball for the Harlem Globetrotters over the winter. (Robinson starred in football, basketball, and track as well as baseball in college, and some felt that baseball was his weakest sport.) Aside from the normal wear and tear of the long baseball season, Jackie was suffering from a painful bone spur on his right ankle that would require surgery over the winter.

So why, exactly, would Robinson agree to suit up for a meaningless pair of ballgames? The presence of William “Dizzy” Dismukes is almost certainly the answer.

Dizzy Dismukes, an “old school” Negro Leagues pitcher and executive who had managed the original 1932 Detroit Wolves, returned to Detroit to manage the “new” semi-pro Wolves in 1947. Dismukes had pitched and managed for more than two decades in Black Baseball before becoming an executive with the Kansas City Monarchs. In the 1950s, Dismukes would become a full-time major-league scout for the Yankees and White Sox as the final act in a career that literally spanned a half-century in the game.

According to eminent Negro Leagues historian James A. Riley’s Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues:

[Dismukes] eventually moved from the dugout to the front office and became the Monarchs’ traveling secretary for many years as well as their personnel director from 1942 to 1952. In this capacity, he was instrumental in acquiring Jackie Robinson to play with the Monarchs in 1945. He recognized Robinson’s deficiency at shortstop and asked Cool Papa Bell to convince Robinson that this was not his best position.

No one could have expected Robinson, at the apex of his fame, to extend himself further to help an old Negro Leaguer who was managing an obscure semi-pro team in a little-known wooden ballpark on the hardscrabble soil of North Detroit — yet he did.

Robinson suited up and played two more ballgames in 1947. The games featuring the Dodgers’ star drew an estimated total of 15,000 fans to Dequindre Park, which was said to have been renamed Jackie Robinson Stadium in honor of the famous guest.

Robinson had played previously in Motown, appearing in a neutral-site doubleheader at Briggs Stadium, home of the American League’s Detroit Tigers, in July 1945 when Satchel Paige and the Kansas City Monarchs played the Memphis Red Sox. Paige & Company drew a crowd estimated at 25,000–30,000 to Briggs Stadium as the Monarchs swept the doubleheader from the Red Sox while the Tigers were on the road.

The Tigers went on to win the World Series in 1945. Their massive steel and concrete, double-decked structure at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull, adjacent to Detroit’s busy downtown, could seat 58,000 fans and was the kind of venue in which Robinson should have been playing in 1947, rather than in out-of-the way Dequindre Park, six miles north of the city’s business and financial core.

Following the action

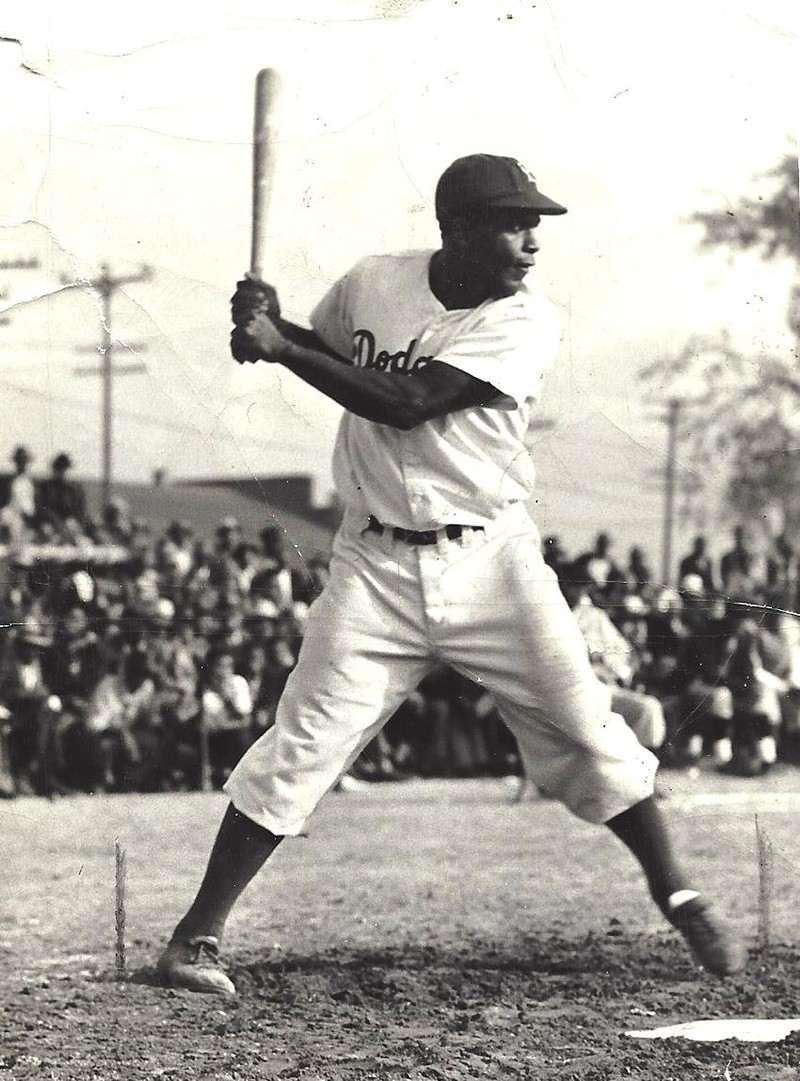

These two exhibition games featuring Robinson were big news in Detroit’s African American media. Both the weekly Detroit Tribune and the Michigan Chronicle newspapers covered the games and included pictures of Robinson at the ballpark.

Robinson’s appearance was so important that the two White candidates for Detroit mayor — facing a November 4, 1947, general election — stumped for votes at Dequindre Park. Incumbent mayor James Jeffries and challenger Eugene Van Antwerp were pictured separately in the Tribune alongside Robinson, obviously looking to sway the minds of both the Black and White fans that had turned out. (Van Antwerp would win the non-partisan election with 52 percent of the vote.)

The Chronicle, the oldest African American newspaper still published in Michigan, featured a reverse-type banner headline, “Joe Louis or Jackie Robinson . . .Which?” above a long piece by veteran Black Detroit scribe Russ Cowans. Cowans discussed the relative fame and popularity of the two transcendent Black athletes below subheads that read:

ROBINSON HAS MADE HIMSELF VERY POPULAR

Many Fans Believe He Is More Popular Than Joe Louis

The Chronicle even ran a page one photograph in its October 18 edition of Robinson’s family members who had traveled to Detroit. The striking and touching image showed Jackie’s wife Rachel; her mother, Mrs. Zellee Isum; his mother, Mrs. Mallie Robinson; and his sister, Mrs. Willie Mae Walker. While not pictured, Jackie’s and Rachel’s first-born, Jackie Junior, not yet year a year old, was also reported to been part of the family’s traveling party.

In the plus ca change department, the same issue of the Chronicle also included a page one headline demanding a probe into the fatal shooting by Detroit police of a boy accused of purse-snatching.

Not surprisingly, the coverage of Robinson’s appearances was minimal in Detroit’s White media; both the Detroit Free Press and the Detroit News publishing only short notes in advance of Robinson’s appearance. Neither major daily mentioned the game results or even that both mayoral candidates had showed up.

The games, the teams, the players

Led by their famous ringer (and gate attraction) Jackie Robinson, whose brilliant play would earn him the first-ever Rookie of the Year Award from the baseball writers that winter, the Detroit Wolves played games on Saturday, October 11, and Sunday, October 12. Their opponents were the Holy Redeemer All-Stars, a local White semi-pro team.

Who won, you ask? It’s not at all clear, as is regrettably sometimes the case in Black Baseball. The Amsterdam News reported on October 18 that the Wolves were downed by Holy Redeemer by a score of 11–6, while the Atlanta Daily World reported on October 16 and 21 that the Wolves had bested the White team by the same score! Both stories referred to only one game, so either the score of the second game was never reported, or else the teams split the series by reversed but identical scores.

Since these games were exhibitions, the results really didn’t matter, and incomplete press reports were hardly unheard of in that era. Far more important were all things Jackie, including this description of Robinson’s remarks before the first game, published in the Atlanta Daily World on October 21:

Possibly the shortest speech on record was made by Jackie. He said simply, ‘I don’t talk, I play baseball,’ and the crowd roared.

Who were these “new” Detroit Wolves? They were a Black semi-pro team, organized in early 1947, that adopted the name of the powerful 1932 Negro East-West League Detroit club that had played at Hamtramck Stadium. The ’32 Wolves featured five future Hall of Famers — Cool Papa Bell, Willie Wells, Mule Suttles, Ray Brown, and Smokey Joe Williams — and were leading the short-lived league when it folded in midseason.

Teenager Quincy Trouppe also played on the ’32 Wolves; 15 years later, Trouppe was the playing manager of Negro American League’s Cleveland Buckeyes. With Trouppe behind the plate and at the helm, the Buckeyes had swept the Homestead Grays in the 1945 Negro World Series. In 1947, however, Cleveland had lost the Negro World Series to the New York Cubans two weeks prior to Robinson’s trip to Detroit.

Tracking down the players on the ’47 Wolves is as difficult a task as for most Black semi-pro teams of the era, but the Wolves’ lineup that October did include two experienced Black Detroit players alongside Robinson: Charles “Red” House and Andy Love. House had Major Negro League experience with the 1937 Detroit Stars and the 1945 Homestead Grays; he played semi-pro ball for decades and coached and mentored two generations of young Black Detroit players. Love was a standout prep athlete in the 1920s at Hamtramck High School and played for the Detroit Stars in the original Negro National League in 1930 and 1931. He would play semi-pro ball well into his 40s.

On the bench, the Wolves featured two young hotshots from Detroit: 20—year-old Ron Teasley and 19-year-old Sammy Gee. Gee had played in the Dodgers’ farm system in 1947 at the Class C level, while Teasley would join Gee in the Dodgers’ chain in 1948. Both were released by the Dodgers without explanation in midseason ’48 even though they were playing well; both then joined the 1948 New York Cubans in the Negro National League. Like so many other Black players in the late 1940s and early 1950s, both played in Canada where African Americans were treated with the decency and respect they were not accorded by most in the States.

Nicknamed “Schoolboy” because he began playing on adult teams in his early teens, Teasley, now 95, is a Motown legend. He played at Dequindre Park at age 14 in 1941 after the original open sandlot had first been enclosed and upgraded with wooden grandstands. He forged a long career as a pioneering prep baseball and basketball player; a record-setting hitter at Wayne State University; and as a high school teacher, baseball, basketball, and golf coach for decades at Northwestern High School in Detroit.

Coach Teasley is one of only four living Negro League players from the Major Negro League era (1920–1948). Willie Mays is one of the others.

The All-Stars were composed of Holy Redeemer High alumni who played semi-pro baseball (and other sports) against a variety of local opponents. In ’47, Holy Redeemer’s baseball team was the class of Detroit’s CYO major sandlot league, so they were no patsies. They were almost certainly not as experienced as the Wolves, however.

After World War II, Most Holy Redeemer was believed to be the largest Roman Catholic parish in the United States. Its 14,000 parishioners enjoyed an Italian-inspired campus in Southwest Detroit that consumed an entire city block. Holy Redeemer featured a Roman basilica–style church, a campanile, a rectory, a convent, a grade school, a high school, and a gym.

The parish at the corner of Vernor Highway and Junction thrives today, though the convent and the parochial high school have closed. The high school building and auditorium are now occupied by Detroit Cristo Rey, a college prep school operated by the Basilian Brothers of Chicago. Cristo Rey’s athletic teams are, coincidentally, named the Wolves.

After Detroit

Robinson embarked on his month-long stage tour immediately after the two games in Detroit. He was booked for multiple shows at the Apollo Theatre in New York, the Howard Theatre in DC, the Regal Theatre in Chicago, and the Million Dollar Theatre in Los Angeles. The tour lasted until late November.

Reviews of the New York shows were poor, though Robinson was not singled out personally for criticism. Critics understood that the baseball star needed the income and noted that Robinson was genuine and authentic to the audience. A gossip column in the Baltimore Afro-American avoided any judgment, describing Robinson’s performance in DC as “a baseball skit” with famous African American stage and screen actor Monty Hawley.

Sadly, the tour prevented Jackie and Rachel from being with Jackie Junior when he took his first steps with their family in California, shortly before his first birthday—and just before his parents returned home from the tour in November.

Dequindre Park’s fate

The last important game known to have been played at Dequindre Park was a contest between the Detroit Wolves and the Negro American League’s Indianapolis Clowns on August 12, 1948.

The last major event held at Dequindre Park was probably the “Negro Music Festival” advertised for August 27–28, 1948, at the “new Dequindre Park.” Sarah Vaughan and Billy Eckstein were the headliners. Given Vaughan’s and Eckstein’s stature and performance rates, it seems that the venue must have been in decent condition, though the “new” label seems more than a bit odd.

Despite the reports in several newspapers about Dequindre Park having been renamed in Robinson’s honor, printed mentions of Dequindre Park in 1948 and 1949 never used the new appellation.

The only activity at Dequindre and Modern that was reported in the press in 1949 was its use by the City of Detroit’s Parks & Recreation Department for amateur sports. The park, now almost forgotten, was demolished sometime in late 1949 or in 1950. Caramagno Foods today operates a huge warehouse on the site, which also contains an abandoned Vlasic pickle factory.

You just can’t make up a story this good

It is possible that Jackie Robinson was paid for his appearances in Detroit, which doesn’t detract in the slightest from the sublime grandeur of his actions. A short piece in the Sporting News said that Robinson’s agent had booked him for two exhibitions in Detroit at $2,500 each, but the piece included substantial errors that call this information into question.

Arnold Rampersad’s authoritative 1997 biography of Robinson said that Jackie netted only $10,000 for his bookings, so it seems highly unlikely that he could have earned half of that over a weekend in Detroit.

Regardless of any emolument, it can’t be a coincidence that the sole baseball stop on Robinson’s grueling October-November tour would be with a semi-pro club in a city he had no connection with — except for Dismuke’s presence in the dugout. Robinson, without publicly saying so, was obviously doing a huge favor to someone who had helped him reach the mountaintop.

Perhaps the most famous and inspirational of Jackie Robinson’s quotes is, “A life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives.” As a final testament to Robinson’s character, he continued to make charity appearances in various cities during the fall of 1947 despite his other obligations.

Sometimes our idols don’t have feet of clay.

Sometimes our heroes have the heart of a lion, the strength of steel, the endurance of Job, and the character of a saint.

One such hero passed through Detroit 75 years ago this fall en route to immortality in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

R.I.P. Jack Roosevelt Robinson on the 75th anniversary of his own “Shot Heard ‘Round the World.”

Originally published by the Friends of Historic Hamtramck Stadium. It is republished here with permission.

Stay connected with Detroit Metro Times. Subscribe to our newsletters, and follow us on Google News, Apple News, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Reddit, or TikTok.