In late March, hundreds of attendees assembled at San Antonio’s downtown convention center for the 15th annual Border Security Expo, a three-day gathering of the government agents who police immigration and the private-sector vendors who love to sell them expensive things.

On the first day, the crowd, dressed business casual, packed into the main conference room. By video, a 29-year-old goateed billionaire named Palmer Luckey, who’d switched his passion from virtual reality gaming to selling weapons and surveillance equipment to the feds through a company named after a sword from The Lord of the Rings, roused the crowd: “Border Patrol can and should demand more from the vendors here today.” Then, U.S. Border Patrol Chief Raul Ortiz introduced a brief video montage. There was scary music, a tunnel, a long line of brown-skinned asylum-seekers, and a deep-voiced narrator telling us the situation required “constant vigilance.” Agents whipped around on four-wheelers and horses; migrants picked their way through inhospitable Texas scrubland. “Threat,” “the threat,” “threat determination.”

This is standard fare. If you’re in the border security business, you sell fear.

Anduril Industries, the expo’s head sponsor. Christopher Lee/Texas Observer

During the opening panel—sponsored by the goateed billionaire’s company—the rhetoric was tamer than the last time I attended this event, in 2018. These were Biden officials now. At its root, their message was the same: “We need more money and toys to stop immigrants, because reasons,” but they’d remove some blood and vinegar from the pitch. Ortiz, for example, said unauthorized border crossings were too complex to be solved by a wall, and an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) official talked about the role of “alternatives to detention”—releasing refugees with monitoring devices rather than simply incarcerating them.

The tone then reverted with the second panel, when Tom Homan—Fox News contributor, Trump acolyte, and former acting ICE director—took the stage. “I’m pissed off right now. … People are dying because of this open border,” he bellowed, quickly drawing the first enthusiastic round of applause from the crowd. He added that the states of Arizona and Texas were looking at declaring an “invasion” under the U.S. Constitution—a legally dubious proposal Governor Greg Abbott said in April he’d been examining.

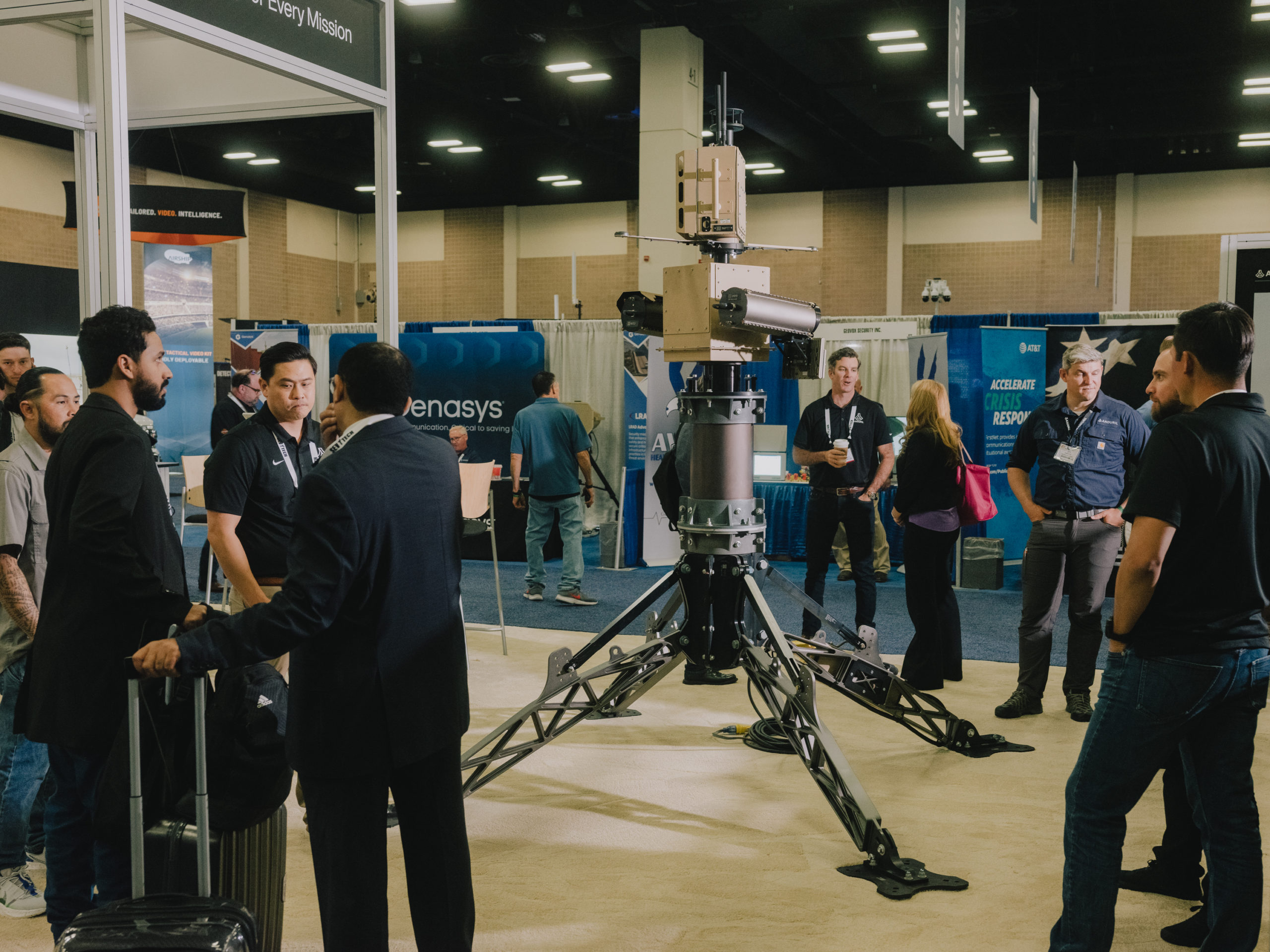

Across the hall in another room, vendors were setting up dozens of booths in rows to hawk their wares: thermal binoculars; facial recognition algorithms; drones and antidrone technology; all-terrain vehicles; good old-fashioned guns; and, somehow, an entire helicopter.

During an audience question-and-answer session, Charles Maley of the South Texans’ Property Rights Association, dressed neatly in Texas-formal attire, struck a skeptical note.

“When I look at the industrial military complex building up in the other room, and I see the billions of dollars being made south of the border and the billions being made north of the border, I wonder if anyone really wants to solve this problem,” Maley said. Another attendee sitting near me commented: “No one’s touching that one.”

opening panel discussion Christopher Lee/Texas Observer

Over on the vendor floor, I wandered along the rows, attempting to eavesdrop. This was a largely futile exercise, since the language of border security is intensely opaque, technical, and euphemistic, but there were certain themes: the more “autonomous” the better, and same for “interoperability.” The buzz this year seemed to be about turning over as much as possible of the work of policing our bloody hemispheric divide to the robots—so I realized I had to find the dog.

Late last year, the internet discovered the advent of a robot, being tested by border agents, that looks roughly like a headless dog with knee problems, leading to a rash of headlines such as “Welp, Now We Have Robo-Dogs With Sniper Rifles.” At a booth run by Ghost Robotics, I found one in the anodized-aluminum flesh, though sans sniper rifle.

Michael Subhan, chief marketing officer, informed me of the proper name: “quadrupedal unmanned ground vehicle”—Q-UGV for short. It could enter a dangerous house and climb the stairs; it could perform perimeter patrols; it could detonate explosive ordnances, he said. At a base price of $150,000, he’d already made some sales that day. “We’re OK with people calling it a robot dog,” he said. “We’re here to keep humans, and canines, out of harm’s way.”

At 4:00 p.m. came cocktail hour, sponsored by the Fortune 500 military contractor SAIC.

As this first day came to a close, migrants from various countries around the world fled various degrees of grinding poverty, climate change-induced food insecurity, endemic armed conflict, and lack of access to COVID-19 vaccines. The Biden administration—while liberalizing the immigration system in some ways through executive action—continued to enforce Title 42, a Trump- and COVID-era measure that effectively gutted the legal asylum system on public health grounds. That program is now set to end in late May, if the courts allow.

Meanwhile, the president’s ambitious immigration reform bill, sent to Congress on his first day in office, languishes, extending a now decades-long legislative failure. Biden does have different immigration priorities than Trump—ratcheting down construction of a physical wall and the deportation of immigrants without serious criminal convictions—but he still supports funneling ever more money into the Border Patrol and surveillance tech, fueling a border security industry worth billions. In a disturbing sign, Border Patrol reported a historically high 557 migrant deaths last year, a tragedy often caused by the dangerous routes travelers take to avoid detection.

On the morning of day two, after a rendition of the national anthem, officers of various stripes placed starspangled banner-sized flags on the main stage, emblazoned with the logos of their respective federal agencies, followed by a recitation of the names of Border Patrol agents who’d died “in the line of duty” in the last two years—COVID being the leading cause. The agents, though not soldiers, marched off stage in slow unison: “left, left, left, right, left.”

As the ceremony wrapped up, two attendees in front of me compared notes on the liquor they’d consumed the night before: Tequila, Jack, and Fireball. “I don’t even remember going to bed,” one said. At one point, an ICE spokesperson had made sure to introduce me to her colleagues “before we all start drinking later.” In other words, it was a typical conference.

The third and final day brought a change of scenery. A couple hundred miles south of San Antonio, smoke from a spate of wildfires filled the air around a Brooks County ranch. It’s been a bad year for fires. A sheriff’s deputy at the ranch entrance told me he heard one started from “a bailout.” The property was picturesque, full of mesquite and oak. Smiling folks handed out water and free t-shirts. This area is killing country: A vast stretch of hot scrubland, sliced and divided by fencing and surrounding the Falfurrias Border Patrol checkpoint, it’s long been an epicenter of migrant deaths in Texas.

Vendors were out there to demonstrate products, federal agents to test them and participate in a shooting competition. One company representative was demonstrating a broad array of drones, some Americanmade, some Chinese-made and cheaper. He sent one far out over the South Texas brush, showing me the thermal imaging that could be adjusted to highlight the temperature range of the human body.

Next to the drone operator was another vendor that I assumed would be his sworn enemy: a Singaporean company selling a plastic, futuristic-looking gun that cuts off radio signals to drones, paralyzing the flying objects in midair. But, it turned out, they were friendly. At their suggestion, I took the bulky gun and aimed at the black speck against the sky. It worked; the drone froze. Maybe ten yards away, another seller was letting people test out an all-electric ATV customized for law enforcement. One joyrider, siren and lights flashing, smacked into a mesquite branch.

In a far corner of the ranch, an array of human-shaped metal targets were placed in a dug-out berm resembling a small crater. This was the final stage of the “Sharpshooter Classic” shooting competition. Pairs of men, many of them Border Patrol agents, pulled up in Jeep Wrangler Rubicons. Belly-down atop a shipping container, they fired rifles at the metal targets, then rushed down closer to the range for a final pistol round. As the gunfire pounded through the quiet ranchland air, the pairs who’d already finished gathered nearby to discuss video games.

The winners, it would turn out, were two Border Patrolmen from the Rio Grande Valley. When an event organizer announced their victory, she made sure to plug the sponsors: Hero Loan and Dell Technology. Nearby, Rudy’s BBQ had brought more food than the group here could possibly consume. There were extra t-shirts, too, and bottled water galore. Someone announced that the shooters hadn’t nearly exhausted the free donated ammunition, either: They’d better get back out and find something to shoot. There we were, just 70 miles from the Mexican border, but this was America baby. Who could resist such excess?