When Tony Lai opened his first Aji Ichiban snack store in Hong Kong in 1993, a British flag flew on top of Government House and China’s gross domestic product per capita was about the same as that of Nigeria.

The chain grew to become iconic for tourists to the city, selling a range of East Asian snacks to residents and visitors. Over the years, it weathered both recessions and typhoons.

But this month, after three of the most tumultuous and transformative years in Hong Kong’s history, Lai was forced to close all 20 of his remaining stores.

The reversal of the entrepreneur’s fortunes is emblematic of the new, embattled Hong Kong. Since 2019, the city has seen the most forceful anti-government protests on Chinese soil since Tiananmen Square, zero-covid border controls that have devastated the economy and a crackdown on dissent that unstitched the city’s social fabric.

Together they have crushed its tourism market, muted its once vibrant culture and sparked an exodus of residents — resulting in arguably Hong Kong’s greatest ever peacetime crisis.

Authorities insist the situation is temporary. The tourists will return when borders reopen, they say, and any outflow of local residents will easily be replenished by millions of talented professionals from the mainland.

China’s president Xi Jinping, who will visit the city on July 1 to mark 25 years since the handover from the UK to China, has instructed the city’s new chief executive John Lee to launch the city into a “new era”. Interviews with business leaders and data compiled by the Financial Times suggest that Hong Kong will be less international and closer to China, both economically and culturally.

For many living in the city, it is a watershed moment for Hong Kong. “At this point, we can only know our fate by rolling the dice,” Lai says.

Asia’s world city

After the British handed over Hong Kong to the Chinese, the authorities attempted to burnish its international credentials. In 2001, Hong Kong rebranded itself as “Asia’s world city” to try and combat post-handover concerns the city would be perceived by global business as another part of China, subject to communist rule.

But the branding scarcely mattered as Hong Kong’s fortunes rose alongside China’s economic boom. The city rocketed up rankings of the freest international economies and global investment banks rushed to expand in the city.

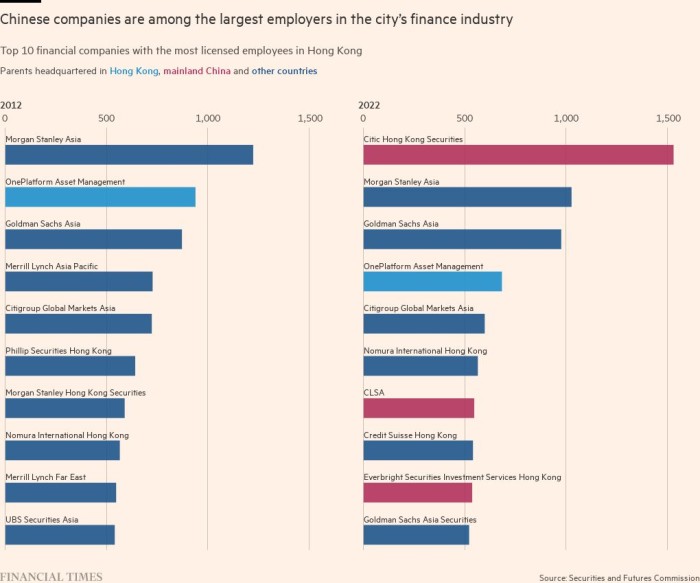

By 2012, American banks were the biggest employer of financiers. At that point, China’s economic output was about half the size of the US.

“There was always a buzz in Hong Kong,” a senior Singaporean businessman in the city says. “Foreign firms looked to Hong Kong as the gateway to mainland China, so there’s a lot of history and investment here, they set up substantial offices.”

With the guarantees offered by its British common law legal system and international stock market, Hong Kong cemented its importance as the window to invest in Chinese companies, who quickly expanded their presence as the economy grew.

In the past few years, however, Chinese companies surpassed western peers as the dominant force in Hong Kong’s corporate world. The city’s largest employer of staff among financial groups is now the Shenzhen-headquartered Citic Securities.

In banking and the law, both Chinese and international companies became more and more likely to be dominated by employees from the mainland, to match the make-up of their clients. “When I hired I would always prefer someone with a western education who speaks fluent if not native Mandarin,” the American lawyer adds, referring to China’s national tongue.

Now, being a native Mandarin speaker means you are more likely to out-earn those speaking Cantonese, the Southern Chinese language spoken in Hong Kong, according to Liu Pak-wa, an economics professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

“In 1991, the [Mandarin]-speaking male migrants earned on average 16.8 per cent less than the Cantonese-speaking migrants but by 2016 they earned on average 34.6 per cent more,” Liu says.

The city was a chief beneficiary of the so-called “China miracle” as the country built its services, trade and tourism sectors. At the Hong Kong tourism industry’s height in 2018, 65mn visitors came in a single year, four-fifths of whom arrived from the mainland.

Local restaurant baron Simon Wong, who oversees a portfolio of more than 45 franchises as the head of the Hong Kong listed LH Group, says the influx boosted his bottom line, especially in city centre districts. “Pre-pandemic mainland Chinese tourists made up about 30 per cent of our customers at our restaurant outlets in Tsim Sha Tsui and Causeway Bay,” he says.

Three years of change

The party came to a halt for the city’s tour operators, hoteliers and retailers in 2019, when anti-government protests broke out in opposition to a proposed law to allow for criminals to be transferred to the mainland for the first time.

The demonstrations snowballed into an unprecedented public revolt against not just the city authorities but the Chinese Communist party in general. Protesters and pro-democracy activists accused the Hong Kong government of eroding the “one country, two systems” guarantee of autonomy that the Chinese had agreed to post-handover.

Tourism numbers from the mainland plummeted after Chinese state media gave heavy publicity to a number of incidents of demonstrators targeting mainlanders.

In response to the protests, Beijing imposed a draconian security law on Hong Kong that was criticised by foreign governments and human rights groups. As well as eliminating political opposition, the law paved the way for a broad reordering of civic life to bring citizens closer to mainland China. Organisations deemed unfriendly to the government were wiped out and children as young as six are now subject to nationalist education.

Scores of Hongkongers chose to exile themselves from the city in the wake of the law’s passage, but for many in the business community China’s response to Covid-19 has had a greater impact.

Since early in the pandemic, Hong Kong has implemented a weeks-long quarantine that has driven away newcomers and demanded contacts of Covid-19 cases quarantine at government camps.

Even now, incoming travellers must quarantine for a week despite the city recording hundreds of cases a day, infuriating executives who had previously selected Hong Kong as the regional base in part because of its role as a transport hub.

“Hong Kong was an aircraft carrier you could come in and out of so easily,” says a former managing partner at an American law firm based in Hong Kong. With easy travel routes into south-east Asia for client meetings, “You could have your principal office in Hong Kong and a smaller one in Beijing or Shanghai.”

The rigid pandemic measures, on top of the Hong Kong government’s inability to deviate from Beijing dogma, were seen by many locals, migrants and expatriates alike as an expression of where the city was heading.

Many decided enough was enough. Since the start of the year, more than 130,000 people have left Hong Kong. At least 123,400 more have applied for the British National (Overseas) UK migration scheme set up in the wake of the 2019 pro-democracy protests.

Even some mainlanders initially attracted to Hong Kong’s culture and spirit no longer see the appeal. “Even as an outsider, I also keep wondering why Hong Kong ends up like this,” says Li, a 27-year-old mainland migrant to Hong Kong who plans to move to Canada with her partner later this year. “When I was in college, Hong Kong was a very inclusive and free place.”

Companies have been temporarily stationing a proportion of their staff elsewhere in Asia, a situation that as time goes on threatens to become permanent, with global business questioning Hong Kong’s suitability as their base in the region.

“They are going to kill that city, neuter it to the point that . . . it’s going to be just a small Chinese city,” a former senior Hong Kong lawyer says from the firm’s new base abroad.

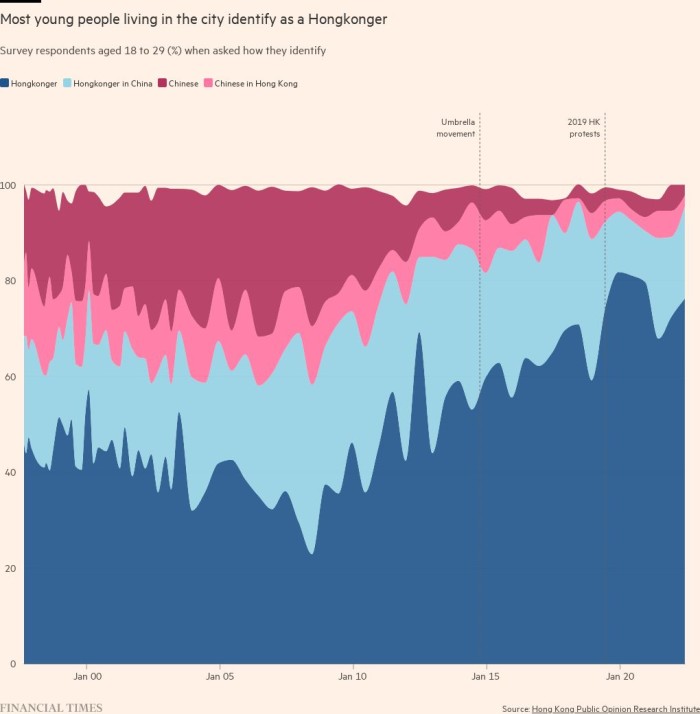

While Beijing has wiped the city clean of public opposition, it has not succeeded at fostering a new sense of Chinese identity. More than ever before, the city’s youth identify as Hong Kongers, with latest figures showing just 2 per cent identified as Chinese.

‘It will be boom time’

Hong Kong has been declared “dead” many times before, however, and still managed to retain its global character.

For all the problems of the past three years, the city still boasts a convertible currency, a bustling port and mechanisms that allow international investors to gain exposure to the Chinese market via Hong Kong. Despite the pandemic restrictions and gloomy atmospherics, no major banks have closed offices in the city.

But the government and its supporters are positioning its post-Covid recovery within an explicitly Chinese context. Rather than tout its role as “Asia’s world city”, government supporters say Hong Kong’s status is assured by its geographic proximity to the dynamism of Southern China.

Officials hold forum after forum to promote business opportunities in the “greater bay area”, a ring of growing mainland cities that surround Hong Kong populated by more than 70mn. The area includes the tech hub Shenzhen whose development the mainland is attempting to foster with tax and other economic concessions.

Last year, the city launched the “Wealth Connect” scheme, which allows city residents to buy mainland investment products sold by banks in cities in Guangdong, Southern China, and is estimated to allow fund flows of more than $46bn.

Last year, Hong Kong handed out more work visas to mainlanders than to foreigners for the first time since records began in 2016 — yet more evidence of its shifting demographics as it grows more economically intertwined with the mainland.

One of these migrants is Sun, an options trader originally from the mainland who graduated from the Chinese University of Hong Kong in 2014 with a business degree.

Sun, who only provided his surname as he was not authorised by his employer to speak publicly, left to work at a Shenzhen-based securities group for five years. But now that Beijing has tightened regulations of the sector, he has decided to move back to Hong Kong.

“A stable regulatory environment is a requirement for the development of an industry,” Sun says. “When it comes to policymaking, I think Hong Kong is more thoughtful, while the mainland is . . . arbitrary.”

One senior Hong Kong property developer says it is still filling out leases with mainland companies, and says no other Asian city is so well positioned to benefit from the rise of southern China once authorities allow more freedom of movement and quarantine-free access.

“If you dwell on the present you would have a mental breakdown,” the executive says. “But this will all unravel and it will be boom time.”

The executive, like many waiting out Hong Kong’s current malaise, points to the city’s history of boom and bust. Li Ka-shing, the city’s iconic business magnate, made his fortune picking Hong Kong’s down cycles. In 1967, widespread anti-government riots broke out after an industrial dispute at an artificial flower factory he owned, cratering the property market. Li saw the buying opportunity and profited as prices recovered.

Regional rivalry

The government is eager to paint a portrait of a pending economic recovery fuelled by the return of mainland capital and talent. But businesses still say it is increasingly difficult to convince people to come to Hong Kong from elsewhere in China.

Lee Siu-yau, an associate professor studying demography at the Education University of Hong Kong, says the idea that the Hong Kong population can be replenished by people coming from mainland China is not guaranteed. “People in mainland China that are highly skilled, they are very, very mobile.”

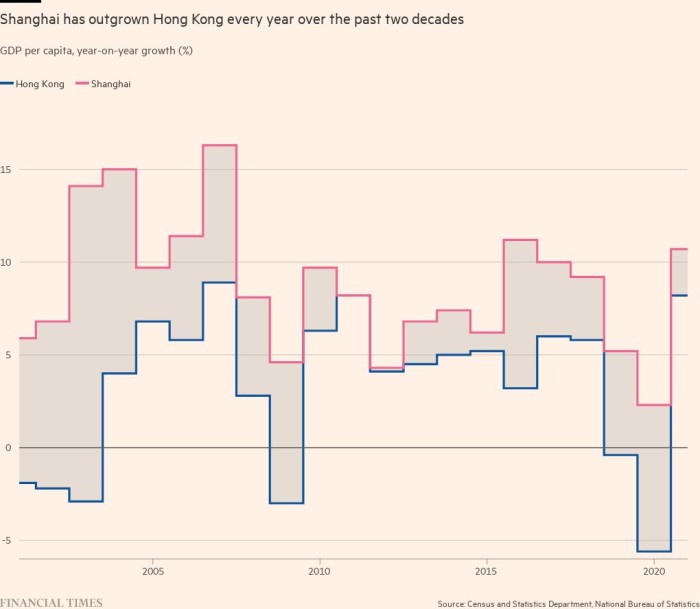

Although it is currently at a lull, China’s rapid economic development also means the territory is increasingly in competition with mainland cities in the greater bay area and beyond.

“China’s economy has been improving rapidly and the living standards have become much better than before,” says Alexa Chow, managing director at recruitment consultancy ACTS Consulting, who estimated there were 20 to 30 per cent fewer mainlanders working in Hong Kong than before the pandemic. “It is a valid question whether mainlanders working in Hong Kong who have gone back there and worked steadily for one or two years would necessarily come back.”

It is not just the halt in the flow of people that is a problem. Gary Ng, of French investment bank Natixis, points to a shift in trade patterns since the pandemic, with less Chinese trade being re-exported via Hong Kong.

China has refused to allow the city to bring back quarantine-free travel, and for a period earlier this year even forced truck drivers to isolate, slowing cross-border trade via road to a trickle.

“Things that have changed because of Covid can become increasingly permanent,” Ng says. “If we continue to see supply chains shift from Asean and India, Hong Kong could lose part of the trade and its role in the global supply chain.”

Much more uncertain and material for the local economy is the return of tourists, Ng adds, especially with the slowing Chinese economy. Without import and sales taxes from tourists, many of the flagship stores of luxury fashion houses have shuttered during the pandemic.

Chinese tourists unable to travel outside of China have increasingly been travelling and spending at home, including on the sandy shores of Hainan Island, where authorities have cut taxes on luxury purchases.

At least one mainlander will be returning to the city for the first time since before the pandemic this weekend, when Xi touches down to commemorate the handover and attend Lee’s signing-in as chief executive.

Hong Kongers may wonder what the city will look like after another 25 years, when Hong Kong’s autonomy from the mainland that was promised during the handover officially expires in 2047.

In a city of legendary self-made tycoons, Aji Ichiban’s Lai is weighing whether the city is one where entrepreneurs like himself have a future and his shops can reopen. “To those who miss Aji Ichiban, I want to say we hope to return someday,” he says.