When my father was born, in 1943, our farm was still powered by horses. Today he frets about the cost of a 345-horsepower tractor and follows the latest developments in “agtech” robotics.

Farming has always involved detours and distractions. One adventurous ancestor moved into livestock ointments in the 1830s (Battles Maggot Oil remains a shepherding staple); and, since my conservationist mother arrived on the scene 40 years ago, we have worked to protect and encourage wildlife. But throughout this time — in fact, since the birth of an agrarian civilisation around 9500BC — the main purpose of farming has been clear and unerring: to produce food for human and animal consumption.

That is no longer a given. My father’s lifespan has borne witness to the most dramatic transformation of agriculture in several millennia — and more radical change is likely to be just around the corner.

While the war in Ukraine has disrupted exports and future harvests in one of the largest grain-producing nations and highlighted the precarity of global food supplies, the distinction between feeding the world and destroying it hangs in the balance. The intensification of agriculture, largely as a result of post-1945 policies designed to avert food shortages, is now considered by many to be the primary cause of environmental destruction.

As Sarah Langford writes in Rooted, her memoir-ish account of farming’s recent past and a meditation on its future, “my grandfather, Peter, was considered a hero who fed a starving nation. Now his son Charlie, my uncle, is considered a villain, blamed for ecological catastrophe and with a legacy no one wants.”

The truth is: we are all complicit in farming processes. The surprising success of books such as James Rebanks’ The Shepherd’s Life, together with a growing interest in previously obscure subjects including rewilding and “soil health”, suggests that people are increasingly aware of this, and of the current window of opportunity to ensure a better future. Can agriculture now solve some of the manifold problems it has helped to create?

At the heart of the debate is whether 21st-century farmers can somehow blend the roles of food producers, conservationists, carbon sequesters, leisure providers and linchpins of the rural community. Or whether the very term “farmer” — along with the practice and sociocultural history with which it is associated — will soon become obsolete.

For Langford — as for Jake Fiennes, conservation manager at Holkham Estate in Norfolk and author of Land Healer — the former is achievable. These two authors set out a case for the continued production of meat and arable crops through “regenerative” agriculture — broadly, a form of farming that seeks to replenish and enhance natural ecosystems. Their focus is the UK, and on local or even individual improvements that can contribute to the greater good. For George Monbiot, who in Regenesis describes farming as “the most destructive force ever to have been unleashed by humans”, the only way forward is a radical overhaul of global food production and eating habits.

By some way the most ambitious and deeply researched of these three books, Regenesis begins with the idea that global food production has developed into a “complex system” — a self-organising network that can transmit shocks in unpredictable ways. The narrowing of diets, crop varieties and corporate power structures over the past 50 years means the system is now increasingly vulnerable to collapse, and yet the warning signs have “scarcely ruffled the surface of public consciousness”.

As an environmental activist and vegan campaigner, Monbiot is something of a professional ruffler — and his book exposes, with journalistic flair, the “gulf between perception and reality” about where and how our food is produced. He wades through slimy water in the River Wye in Wales, where run-off from industrial chicken farms is causing frequent algal blooms. And he reports innumerable horrifying facts, from the quantities of microplastics in fertilisers to statistics on the scale of “Insectageddon”.

Regenesis dovetails neatly with Monbiot’s 2013 book Feral, which made a persuasive — and, it turns out, impactful — case for rewilding. While “regenerative” champions believe that a form of low-intensity mixed livestock and arable farming is the best way to produce food and at the same time care for nature, Monbiot uses his latest book to argue that we should “rewild most of the land now used for farming”. As for how to enact this revolution, he proposes universal veganism — which, he says, would reduce the amount of land used for farming around the world by 76 per cent — and a completely new approach to growing plants.

Featured titles

The book includes some fascinating case studies. There is Iain Tolhurst, a fruit and vegetable grower in Oxfordshire who has developed a “stockfree organic” (without use of livestock products, including manure) approach to horticulture. In a chapter titled “Farmfree”, we meet Finnish entrepreneur Pasi Vainikka, whose food-tech start-up creates protein flour from a soil bacterium. These producers are mostly referred to as “cultivators” or “growers”; if farmers appear in this vision of the future it is in partnership with scientists or as “small farmers [practising] high-yielding agroecology”.

Though bristling with ideas and indignation, Regenesis is not lacking in humour. Railing against the popular television shows that romanticise livestock farming, Monbiot writes: “If the BBC were any keener on sheep it would be illegal.” If the book does fall short it is in providing an off-ramp, as it were, for conventional farmers. Although acknowledging “the Counter-Agricultural Revolution will be extremely disruptive”, he suggests little more than repurposing “vast” government livestock farming subsidies from “helping people to stay in the industry to helping them leave it”.

Whether or not Monbiot’s assertions materialise in the coming years, it surely makes sense to encourage farmers to do more for the environment, rather than pushing them towards a position of alienated belligerence.

Langford’s previous book, In Your Defence (2018), was a quietly devastating exposé of the failures of the British justice system, told through her own experience as a criminal and family barrister. With Rooted, Langford — who has swapped the law for running a family farm in Suffolk — adopts a similar approach to highlight the yawning disconnect between city dwellers and the rural populace, between the ruddy-cheeked farmer of popular myth and the harsh realities of life faced by most farmers in the UK.

Like Fiennes, Langford is quick to point out the harm and hypocrisy of pinning all of our collective environmental failings on farmers: “I read and hear so many words of blame about farming but far fewer of responsibility.” With the suicide rate for the UK’s male farm workers at three times the male national average, these are not empty sentiments.

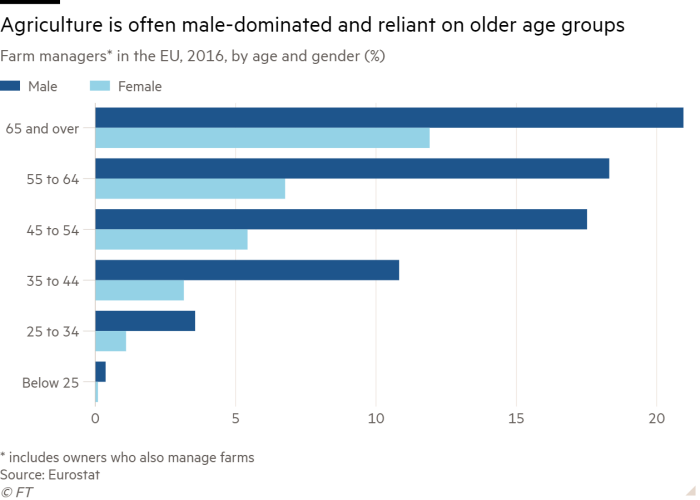

Rooted contrasts Langford’s stilted but rewarding experiments in regenerative agriculture on her own farm with the attitudes of her uncle Charlie (a “Brexit-supporting, climate-change sceptic in a checked shirt and wellingtons”), who feels resentment at being demonised for simply doing his job. It hints at seismic shifts ahead, in a country where the average farmer is just under 60 and yet agriculture is one of the fastest growing subjects at UK universities.

One of the most affecting chapters follows Rebecca and Stuart, a couple whose pig-farming business was destroyed by tragedy and disease in the 2000s, and who overcame numerous hurdles to start over again with a small-scale dairy herd, a focus on soil and environmental improvement, and a thriving farm shop.

Langford is at times gratingly solipsistic: on a visit to London she consciously links herself “to the lapwings that rise up from Hampshire stubble fields; to the frogs that spawn in Cumbrian streams; to the hare that runs on East Anglian maize strips”. And the drama of individual lives is a little overcooked. But Rooted offers a refreshing perspective on an overwhelmingly masculine world, and the stories it contains coalesce into a powerful narrative of struggle and innovation.

Though no less sympathetic to the predicament facing farmers, Fiennes’s tone is bracingly straightforward from the off: “I firmly believe that the natural world is not totally fucked,” he writes at the start of Land Healer. “We can fix it.”

The writer belongs to that clan of famous Fienneses. While his elder brother Ralph is well known for performing the great Shakespearean roles, Jake — with his blunt and somewhat geezerish charm — might have walked off the set of a Guy Ritchie movie, albeit one set in rural East Anglia. After a rustic upbringing, and a stint in nightclub work, he fell into gamekeeping but in time developed an interest — then a career — in ecology.

In a chapter titled “Hedge Porn”, he explains that he started to enhance the “natural capital” of one of the farms on the estate, beginning with leaving hedges untrimmed. Elsewhere, he details the benefits of establishing flower-rich margins and practising light tilling as opposed to deep ploughing.

Fiennes admits he is neither a farmer nor a landowner (Holkham, home to the Earl of Leicester and one of the country’s grandest estates, certainly has more financial heft than most farms), but Land Healer is in many ways a practical guide to “small changes that could save the countryside for farming and for nature”. It could, however, have benefited from a more cogent argument built around the assertion made by the ecologist Colin Tubbs that English biodiversity peaked in the late 18th century, after the land had been farmed for thousands of years.

If there is one subject on which the three authors agree it is the importance of soil. A mind-blowingly complex ecosystem that has, until very recently, been overlooked, soil — and more specifically, its health and fertility — offers solutions to several urgent problems, from food production to wildlife conservation and carbon sequestration. It’s clear that soil will be central to the ongoing debate. As Monbiot writes, “the future lies underground.” The question is: how best to utilise and protect this fragile resource?

Meanwhile, the deepening economic and humanitarian crisis in Sri Lanka, in part the result of a sudden, experimental switch to organic farming in 2021, demonstrates that there is no such thing as a quick fix. Agriculture will have to adapt to dramatic shifts over the coming years that include climate change, food shortages, geopolitical and corporate disruption and the whims of individual government policy. The results of these changes will impact the lives, not just of farmers, but of every single person on the planet.

Regenesis: Feeding the World Without Devouring the Planet by George Monbiot, Allen Lane £20/Penguin $18, 352 pages

Rooted: Stories of Life, Land and a Farming Revolution by Sarah Langford, Viking £16.99, 368 pages

Land Healer: How Farming Can Save Britain’s Countryside by Jake Fiennes, BBC Books £20, 272 pages

Laura Battle is the FT’s deputy books editor

Data visualisation by Keith Fray

This article has been amended since original publication to clarify the breadth of Colin Tubbs’ biodiversity argument

Summer Books 2022

Just last week, FT writers and critics shared their favourites. Some highlights are:

Monday: Economics by Martin Wolf

Tuesday: Environment by Pilita Clark

Wednesday: Fiction by Laura Battle

Thursday: History by Tony Barber

Friday: Politics by Gideon Rachman

Saturday: Critics’ choice

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café