[ad_1]

A 7.8-magnitude earthquake struck Turkey and Syria on 6 February, killing more than 47,000 people.Credit: Salwan Georges/The Washington Post via Getty

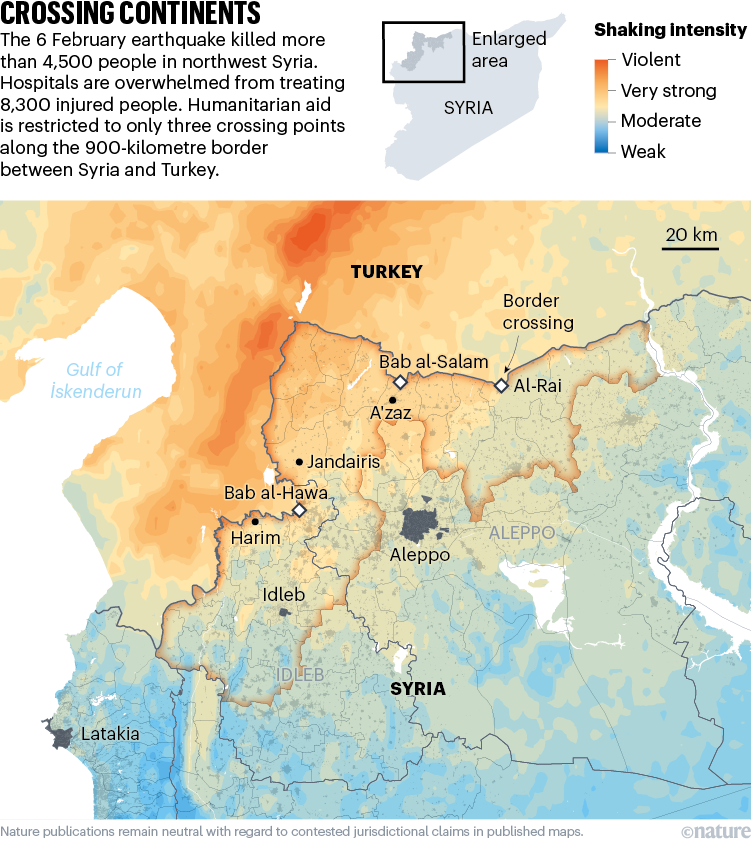

The 7.8-magnitude earthquake that struck Turkey and Syria on 6 February has killed more than 50,000 people and flattened multiple cities. More than 4,500 of those who died, and 8,500 injured, are in northwest Syria, a region with no unified government that has been cut off from the world for more than 12 years amid a devastating war. Its already-depleted health-care system — 4.7 million people share just one MRI machine — is on its knees. More than 10,000 buildings are completely or partially destroyed, leaving 11,000 people homeless, according to the United Nations humanitarian agency, OCHA. The earthquake also destroyed warehouses that store medicines. Nature spoke to doctors, engineers and other experts on the ground, as well as those helping remotely from Europe and elsewhere in the Middle East. This is what they have said.

Credits: Earthquake intensity data: US Geological Survey. Waterways: Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team. Buildup: AtlasAI. Administrative boundaries: UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

After the 2011 Arab Spring, Syria’s government used military force against all opposition. Around 60% of northwest Syria’s 4.7 million people are internally-displaced, having fled bombing attacks from the government of Bashar al-Assad with military backing from Russia.

The United Nations and aid agencies are struggling to get supplies and expertise to earthquake-affected areas, because there are only three temporary crossing points along the 911-kilometre border with Turkey.

Medical emergency

Hospitals in this region have been overwhelmed as they attempt to accommodate thousands of injured people in spaces with severely limited beds, medical supplies, surgical equipment and intensive-care facilities.

More than 8,500 injured people need to be accommodated in only 66 functional hospitals providing 1,245 beds for short hospital stays, according to the WHO. Moreover, all of northwest Syria has just 86 orthopaedic surgeons, 64 X-ray machines, 7 computerized tomography (CT) scanners and one magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machine across the region, according to WHO-compiled data published towards the end of 2022. Gynaecologist Ikram Haboush, director of Idleb city’s sole public maternity-hospital, says “the medical situation in northwest Syria is catastrophic”.

“The supply of antibiotics ran out from day three” after the earthquake, says Abdulkarim Ekzayez, an epidemiologist at King’s College London, who now fears widespread infections. “We have used the medications and serums that would have lasted us for four to six months in two to three days,” adds Haboush. The WHO has started airlifting medicines and medical supplies, but says northwest Syria also needs essential diagnostic equipment such as X-ray machines.

The region’s critical lack of health care is partly caused by hospitals and medical staff being targeted during the war, explains Ekzayez, who is a co-investigator on a UK-funded project called Research for Health System Strengthening in Syria. In a separate study, Ekzayez estimated that as of June 2021, 350 medical facilities had been attacked and 930 health-care personnel killed.

“People are running all over the place to make use of any existing resources, including basic ambulances,” Ekzayez says. “The medical staff have been working non-stop,” adds Haboush, who was working at the maternity hospital in Idleb when the first earthquake hit at 01:17 universal time. The hospital occupies the fifth and sixth floors of a building. “We had to evacuate the incubators and move all the babies to the ground floor,” Haboush recalls.

According to three doctors who Nature spoke to in northwest Syria, the most common injuries are limb fractures, trauma injuries, crush injuries including ‘crush syndrome’ (damages that result in organ dysfunction including kidney failure) and bleeding.

People with crush syndrome need intensive care and dialysis, says cardiologist Jawad Abu Hatab, who is dean of medicine at Free Aleppo University in northwest Syria. However, the region has only 73 renal dialysis machines, according to the WHO-compiled data.

“There were also cases of cardiac arrests from the shock and horror of the catastrophe,” Abu Hatab adds. The medical community is also preparing to deal with more cases of post-earthquake trauma, especially among children and women.

Doctors say that they urgently need more dialysis machines and orthopaedic-surgery equipment, along with painkillers and antibiotics. “These supplies were not abundant before the earthquake,” and will now run out, says Haboush.

Rescuers searched for survivors in the rubble of collapsed buildings in Harim, one of the towns with the highest number of deaths and injuries.Credit: Omar Haj Kadour/AFP via Getty

Naked-eye damage assessments

Volunteer engineers are going house-to-house checking which of some 8,500 earthquake-damaged buildings are safe enough for people to return to. But lacking in the necessary tools and safety equipment, they are resorting to tapping walls with household implements such as simple hammers and making decisions using the naked eye.

It is painstaking work. As of 25 February, around 2,644 of the damaged buildings had been assessed, according to the Association of Free Syrian Engineers , a voluntary group based in A’zaz, near Aleppo, that is coordinating the effort.

At the same time, experts from the Syrian diaspora are helping with virtual assessments in places inaccessible to local engineers. Residents of damaged buildings are taking photos and videos of the interiors and sending them to members of the Syrian Engineers Association in Qatar, based in Doha.

“Assessing the structural status of buildings is as urgent as the medical situation and should not be underestimated because aftershocks are still on-going says Muhammad Azmie Tawackol, a civil engineer and the association’s president. But in northwest Syria, people are having to use whatever methods are available, he adds.

The engineers are trying to estimate whether buildings are inhabitable (safe with minor cracks), temporarily unusable (needing reinforcement) or unsafe — in which case occupants must evacuate immediately.

Buildings in danger of collapsing are being reinforced with whatever materials are available, irrespective of whether they are suitable. Carbon-fibre-reinforced polymers would work better for seismic reinforcement, Mohammad Khear Hayek, an engineer with the volunteers association, told Nature. Instead, they are having to use brittle industrial iron. “We are in an emergency situation, so we must respond quickly using the resources that we have,” Hayek says.

The engineers association based in northwest Syria is collating data daily and “the next step is to analyse the reports and produce statistical studies, which will be important in the reconstruction phase”, says association member Ali Hallak, a computer engineer.

Many buildings will need to be rebuilt, but there is a shortage of engineers in northwest Syria, says Hayek. Before the earthquake, “we talked about a need to train engineers on reconstruction according to appropriate safety standards”, Hayek says. “Now this has become a necessity,” he adds.

[ad_2]

Source link