[ad_1]

“Among researchers, I think we’ve reached a consensus that there hasn’t been an exodus of teachers during the pandemic,” said Heather Schwartz, a researcher at RAND, a nonprofit research organization, which regularly surveys school districts around the country about their staffing. “I don’t see many district leaders saying we have a serious, severe shortage of teachers. I don’t see the crisis.”

“Are we going to have such extreme shortages, that we can’t even keep the doors open for schools?” said Schwartz. “No, that’s not where policymakers need to spend their energy.”

Instead, as counterintuitive as it might seem, Schwartz found that 77 percent of schools went on a hiring spree in 2021-22 as $190 billion in federal pandemic funds started flowing, according to a RAND survey released on July 19, 2022. “Yes there’s a shortage in the sense that they have unfilled open positions. But it’s sort of a misnomer to say the word ‘shortage’ because compared to pre-pandemic, there’s more people employed at the school.”

Imagine that Google decided to expand its ranks of computer programmers. It might be hard to find so many software engineers and it would feel like a shortage to IT hiring managers everywhere. That’s what’s happening at schools.

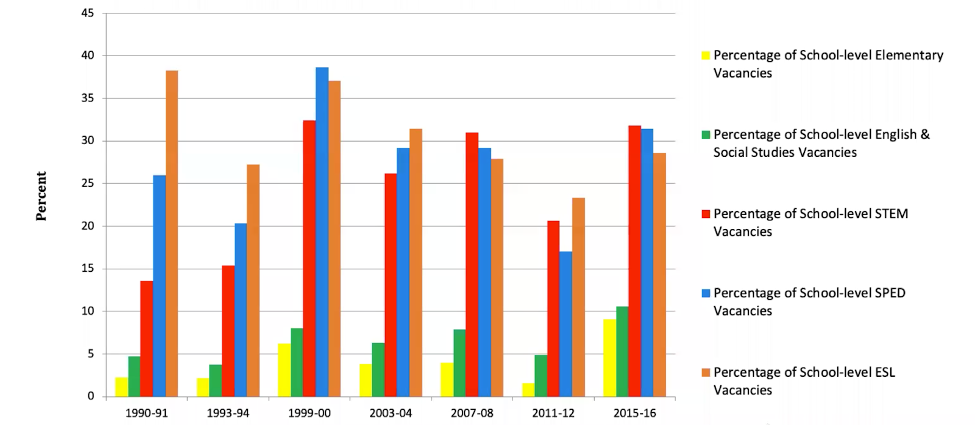

To understand why teacher shortages became a dominant story line, it’s helpful to start the story before the pandemic when complaints about teacher shortages were common. But Goldhaber said there never were shortages everywhere or among all types of teachers. Shortages were concentrated in low-income schools and certain specialties. Wealthy suburban schools might have dozens of applicants for an elementary school teacher, while schools in poor urban neighborhoods and remote rural areas might struggle to find certified teachers in special education or in teaching students who are learning English.

The reasons for the different shortages varied. Many teachers go into special education but soon quit the classroom. Teaching students with disabilities is a hard job. Fewer aspiring teachers opt to specialize in math or science instruction. There’s less interest at the start. Low-income schools have problems at both ends. Fewer people want to teach at low-income schools and once there, departures are high.

When the pandemic hit in March 2020, schools had their usual rate of teacher departures. But hiring shut down along with everything else. Principals found it virtually impossible to replace teachers who had left.

“Imagine this big slowdown of hiring,” said RAND’s Schwartz. “And then you come into the next school year, and you have a shortage of staff — not because there’s tons of people who quit, but because you haven’t refreshed your roster.”

Many teachers fell ill from COVID or took days off to take care of sick family members during the 2020-21 school year.

“So we had this temporary shortage of teachers who are on campus or on the ground on a given day,” said Schwartz. “Districts didn’t have enough substitute teachers to fill those day- to-day shortages.”

The two problems compounded and created extreme shortages. Students sat in classrooms without teachers. Schools closed as variants surged through their communities.

The script suddenly flipped during the 2021-22 school year as the federal government sent pandemic recovery funds to schools. Schools not only resumed hiring to fill their vacancies, they increased their staffing levels to help kids catch up from the missed instruction. Many principals hired extra bodies to keep in reserve in anticipation of new coronavirus variants.

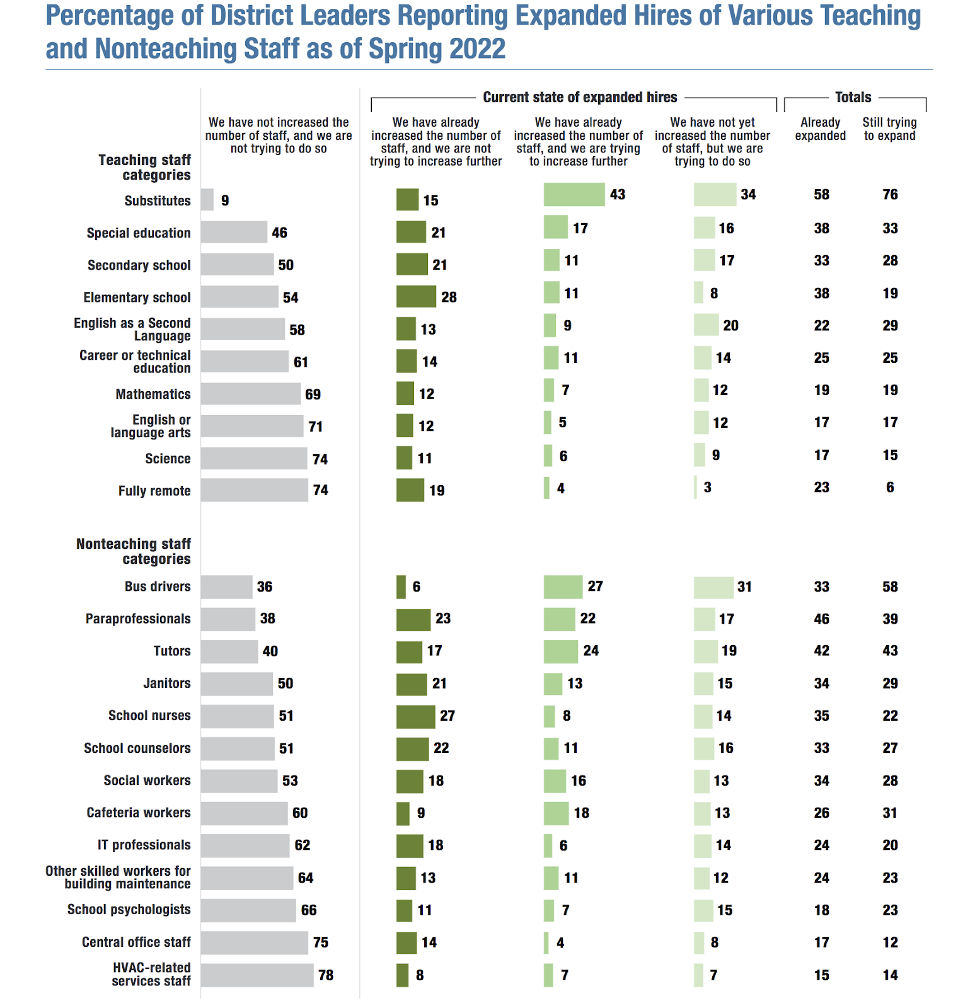

The biggest areas of staff expansion were among substitute teachers, paraprofessionals or teachers’ aides, and tutors. Ninety percent of the schools surveyed by RAND have already increased their ranks of substitute teachers or are still trying to hire more. To lure substitutes, schools increased pay from an average of $115 a day to $122 a day, inflation adjusted, which Schwartz says is a larger increase than in the retail industry.

Schwartz doesn’t yet have data on the exact number of new hires, but she is confident that schools have increased head counts. More than 40 percent of school districts surveyed also said they have already or intend to increase the number of ordinary classroom teachers in elementary, middle and high schools compared with pre-pandemic levels.

“This expansion of hiring is confusing if you’re like, wait, there’s huge teacher shortages,” said Schwartz. “It’s an ironic problem. So many schools were having to scramble just to stay open and staff during severe shortages. Now we have this weird other problem of overstaffing.”

It’s understandable that so many of my media colleagues are writing about shortages. States have been reporting shortages to the federal government, and education advocates, such as Dan Domenech, executive director of the School Superintendents Association, have been sounding alarm bells. Part of the confusion is how shortages are counted. Goldhaber explained to me that there’s no standardized way of defining or documenting a shortage and if even one district among hundreds reported difficulty in hiring a particular type of teacher, some states will document that as a statewide shortage in that category. Louisiana, for example, reports that it is experiencing shortages among 80 percent of its teaching force.

By contrast, RAND’s analysis is more refined. “We asked schools what shortages they expect for the 22-23 school year and they did not anticipate a huge shortage,” said Schwartz. Three-quarters of the districts said they expect a shortage, but most of them, 58 percent, said it would be a small shortage. Only 17 percent of districts anticipated a large shortage of teachers.

Schwartz says her biggest worry isn’t current teacher shortages, but teacher surpluses when pandemic funds run out after 2024. School budgets will be further squeezed from falling U.S. birth rates because funding is tied to student enrollment. Schools are likely to lay off many educators in the years ahead. “It’s not easy for schools to shed staff and maintain quality of instruction for students,” said Schwartz.

That won’t be good for students.

[ad_2]

Source link