[ad_1]

If Labour’s current lead in the opinion polls holds and it wins the next election, lower economic growth, strained trading relationships, stretched public services and weak public finances will present the incoming government with a much more challenging economic inheritance than in 1997.

Unlike the relatively benign problems that faced Tony Blair and Gordon Brown 26 years ago, when Labour won power after a long period of Conservative government, former politicians, officials and current experts expect a Sir Keir Starmer government to be short of luck on economic performance and public funds.

Experts say that if there is a Labour victory in 2024, former chancellor Ken Clarke’s “iron law” of politics — that Conservative governments are there to clear up the mess left by Labour governments — will not apply.

Paul Johnson, director of the independent Institute for Fiscal Studies, says: “As things stand — high inflation, high debt, taxes already at an all-time high — the outlook seems bleak for a new government looking to spend more.”

The Starmer Project

This is the third and final instalment in a series looking at the Labour leader’s plans ahead of an election expected next year — and how he got there

Part one: A surprisingly bold economic agenda

Part two: Ruthless remaking of the Labour party

None of this is lost on Rachel Reeves, the shadow chancellor. Speaking to the FT, she turned the tables on Clarke, saying that while the previous Labour government inherited a “reasonable” position, “what we are inheriting this time is much more of a mess”.

“Liam [Byrne, then chief secretary to the Treasury] wrote some stupid note [in 2010] saying there was no money left, but it is much worse now because this government has borrowed so much more than Labour ever did,” she adds.

Ed Balls, who entered the Treasury in 1997 as Brown’s economic adviser, says that despite the differences with that time, the one thing that appears similar is that “no one is listening” to the Conservatives’ arguments on the economy, regardless of their merit.

“Following Black Wednesday and interest rate rises, it was impossible for the Conservatives to recover from a large macroeconomic failure that impacted on people’s lives,” he says, referring to sterling’s calamitous exit from the European exchange rate mechanism in 1992.

“It may well be that what happened last autumn is similar, in that another failure of macro policy made people fear for their jobs and living standards and may not be recoverable,” Balls adds.

If true, this would help Labour get into office — but will not help a new government emulate the economic performance of what former Bank of England governor Lord Mervyn King called “the nice decade” after 1997.

Economic growth

Since the global financial crisis of 2008-09, the UK economy’s growth performance has deteriorated, both in comparison with historic averages and other advanced economies.

In the 60 years after the second world war, chancellors had to deal with stop-go expansion, recessions, inflation and recourse to the IMF, but the size of the economy still grew at a steady average of about 2.5 per cent a year.

But that ceased after 2008 and there is no sign of a return to those healthy rates. In the five years before 1997, the economy grew 2.8 per cent a year on average, while it is expected to have expanded only 0.2 per cent a year in the five years running up to a 2024 election. The Office for Budget Responsibility, which takes a relatively optimistic view, expects a few years of better performance thereafter before the economy settles down to an annual average growth rate of 1.75 per cent.

Many other forecasters, including the BoE, are more pessimistic.

Across the income distribution, large rises in living standards have been replaced by much more modest gains as households have borne the brunt of low productivity growth and the shocks of the pandemic and energy crisis. Even with the additional government borrowing and state support in 2021-22 to help households through the pandemic, income growth rates have been meagre.

Families may hope that a Labour government can bring better times for living standards. But with productivity growth not firing as it did before the global financial crisis and signs that the world is moving into a more protectionist phase without large gains to be made from globalisation — the opposite of the 1997 experience — Balls is gloomy about the economic backdrop.

“We could not have known it before 1997 . . . but the global economy was moving into a benign period of stronger growth and globalisation that undoubtedly benefited the Labour government in the 2000s,” he says. “It feels unlikely that we will repeat that with the global situation more fractious and less stable.”

Room to improve economic performance

Civil servants and Labour politicians who served in the 1997 to 2010 period stress that the Blair and Brown governments also sought to make their own luck with policy reforms to improve the labour market, reduce worklessness and boost business investment.

While the success of these policies in improving growth rates has long been disputed, there is little doubt that both the Labour government and the subsequent Conservative-led administrations got people back into work, helping to bolster the growth rate.

Unemployment fell after 1997 from 7.2 per cent and now stands at 4 per cent among those aged between 16 and 64 years old, leaving less scope to bring more people into the economy now than then, although there is some scope to bring a smaller number of people back into the labour force from long-term sickness now.

Lord Nick Macpherson, the permanent secretary to the Treasury between 2005 and 2016, says that in the 1990s there were “just a lot of people who could be sucked into the labour force”.

“This time round we have the bizarre situation where there are massive labour shortages, but we don’t have a strategy for supplying labour for the skills demanded. It will be a horrible labour constraint.”

Another former senior Treasury official says that ministers and officials will need to think hard about “industrial policy stuff”, where the UK is increasingly having to compete with big spending and subsidies in the US and other European countries.

“It’s a big strategic problem and half of the Treasury hates the idea [of subsidies] because lots of money will be wasted, while the other half thinks it is necessary,” the former official says.

Public services

A Labour government focused on reviving growth will also have a more immediate problem: satisfying voters’ rising demands for better public services.

This, says Balls, is similar to the situation in 1997, where the health service had been less generously funded than in other European countries and the previous Major government had set out tough spending plans for the two years after 1997, which Blair and Brown had pledged to follow.

“You couldn’t get a hip operation in 18 months and there had been no school building in 18 years,” says Balls.

Some pressures on public services were greater 26 years ago — crime rates were significantly higher, for instance — but most are more severe now.

Waiting lists in the NHS are considerably larger now than in 1997, when Blair told voters on the eve of the election they had “24 hours to save the NHS”. And the public spending plans pencilled in by chancellor Jeremy Hunt for the years after a 2024 election are just as tight as they were in 1997.

The public service pressures will come even as there are more strains in the workforce than in 1997. While the Major government had cut the pay of public sector workers compared with those in the private sector, IFS research shows the relative position was better in the late 1990s. The Blair government was also able to find more money for many parts of the public sector by further squeezing defence spending.

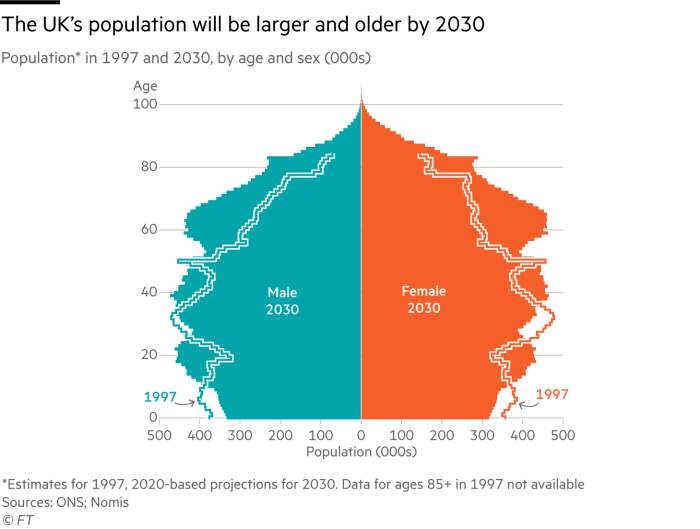

That option is less feasible today against the backdrop of conflict in Ukraine, and none of the other benefits apply either. As the population ages and the baby boomer generation retires — the elderly are significantly more dependent on the working population now than in 1997 — the prospects for funding public services without higher taxes look implausible, according to Torsten Bell, chief executive of the Resolution Foundation.

“Just like in 1997, you’ve got pressures on the NHS, which is not performing well, but what is very different is the prospective growth of the over 65 [years old] population putting upward pressure on the cost of services at the same time as there is a decline in the size of the workforce,” Bell says.

Public finances

If Starmer and Reeves did not have enough to worry about with a slow growing UK economy, a more challenging global backdrop, worse demographics and more stressed public services, they will also be starting from a much less healthy public finance position.

Public sector net debt stood at 37.6 per cent of gross domestic product in May 1997, a level of indebtedness that is now two-and-a-half times as large at 99.2 per cent of GDP in April 2023 and still rising even though taxes have been raised to their highest level since the second world war.

Though many aspects of the public realm in education, health and transport are more modern now than in 1997, the rise in debt has not been backed by an increase in public sector net assets.

The Office for National Statistics’ new summary statistic of public sector net worth has deteriorated from a surplus of £96bn in spring 1997 to a deficit of £611bn at the end of April 2023, after the government borrowed heavily through the global financial crisis, the Covid-19 pandemic and the recent energy crisis.

Reeves is clear that “there is not a huge amount of room for manoeuvre”, saying the government cannot simply borrow its way to better public services. “Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng tested to destruction the idea of deficit financed spending, so it is really important we explain where the money is going to come from,” referring to the former prime minister and her chancellor.

Potential positive news

With such a difficult economic and public finance backdrop for a new Labour government, most economists and former officials warn that the outlook is difficult, but they stress it is not impossible and quite often, in the past, the UK has found that conditions improve just as everyone is despairing.

Johnson of the IFS says: “It is just possible [Labour] could get lucky with the economy. Seven years on from the Brexit vote we have suffered much of the initial hit. Political chaos seems to have subsided. Maybe, just maybe, we will get back to decent growth. Can’t bank on it though.”

Macpherson, too, says history does not all point to doom and gloom about the years ahead. “Just when you think everything is terrible, the economy often turns a corner and I can see some reason that the economy could regain its capacity to grow — the backwash from Covid and energy prices is coming to an end, for example.”

“I can’t see an obvious investment boom about to take place, but it’s important to retain perspective and it’s not like Britain is doing worse than everywhere else,” he adds.

Data visualisation by Keith Fray and Alan Smith

[ad_2]

Source link