Leading economies are close to “tipping” into a high-inflation world where rapid price rises are normal, dominate daily life and are difficult to quell, the Bank for International Settlements warned on Sunday.

In its annual report, the BIS, the influential body that operates banking services for the world’s central banks, said these transitions to high-inflation environments happened rarely, but were very hard to reverse.

Diagnosing that many economies had already embarked on the process, the BIS recommended that central banks should not be shy of inflicting short-term pain and even recessions to prevent any move to a persistently high-inflation world.

Agustín Carstens, BIS general manager, said: “The key for central banks is to act quickly and decisively before inflation becomes entrenched.”

Central banks around the world have started to raise rates quickly in response to soaring inflation, with the US Federal Reserve leading the pack, but the action taken so far does not satisfy the BIS.

In its report, the bank said that there was a deep, “inherently stagflationary” shock hitting the world from higher commodity prices, supply chain bottlenecks and shortages stemming from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

This had increased the prices of the goods and services that households noticed the most, reinforcing the salience of price rises.

“We may be reaching a tipping point, beyond which an inflationary psychology spreads and becomes entrenched. This would mean a major paradigm shift,” the report stated.

Such a shift would mean leaving behind a world where prices have been generally stable, with some things getting cheaper and others more expensive. In this benign world, central banks have been able to ignore temporary surges in oil or natural gas prices because “economy-wide inflation [is] less noticeable [and] also less relevant”.

After a move to a high inflationary period, “price changes are much more synchronised and inflation is much more of a focal point for the behaviour of economic agents, exerting a major influence on it”.

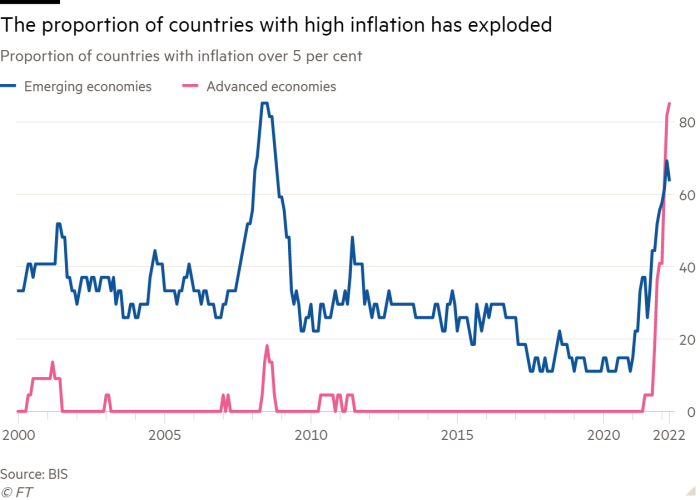

Inflation is at multi-decade highs in several economies, including the US, eurozone and the UK. The BIS was worried the leading economies of North America, Europe and many emerging markets were near a tipping point. Consumers had noticed price rises, large increases had become broad across most goods and falling real wages would generate attempts to recoup the losses.

Ignoring price rises was no longer rational for consumers, the BIS said, which reinforced the danger of a shift to a high-inflation world.

“As inflation rises and becomes a focal point for agents’ behaviour, behavioural patterns tend to strengthen the transition,” it added, predicting companies would fight to prevent profit margins being squeezed and workers would defend their wages. The length of most contracts would tend to shrink, it added, because parties on both sides could not guarantee price levels in future.

To bring down inflation, the BIS said, “some pain will be inevitable”, but it said ultimately the difficulties of entrenched inflation “far outweigh the short-term ones of bringing it under control”.

“This puts a premium on a timely and decisive response,” it told its member central banks, even if none could be certain that they had moved into a high-inflation environment.

The BIS added: “The overriding priority is to avoid falling behind the curve, which would ultimately entail a more abrupt and vigorous adjustment. This would amplify the economic and social costs of bringing inflation under control.”