[ad_1]

Adama Diabaté, a prominent Malian media pundit with a fondness for Moscow, says the Russian military “instructors” who are increasingly visible in the west African country are trusted “100 per cent” by the population.

“Down to the last peasant in the last village, if you ask them who’s working in the best interests of Africans, they’ll say Russia,” he said. The newcomers had done more to counter jihadist insurgents in under a year than former colonial ruler France had in almost a decade, he added.

Diabaté’s view is a one-sided account of events in a country where Russian mercenaries working for the Kremlin-linked Wagner Group have been accused by human rights groups of indiscriminate killings.

But analysts say that using a mixture of truth, half-truths and conspiracy theories, pro-Russian influencers such as Diabaté — some paid but many speaking out of conviction — were tapping into genuine frustrations and sympathies to justify Moscow’s version of events.

“Hybrid” warfare tools, including propaganda, deception and other non-military tactics, are being deployed to unsettle western interests on the continent and bring states and others under Moscow’s influence, they say.

“You basically coerce a specific community through the influence of these talking heads,” said Jean le Roux, research associate for sub-Saharan Africa at the Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), a unit of the Atlantic Council that exposes misinformation. “If you have these narratives infiltrate through the general populace . . . all these ideas are seeded. It’s a lot more organic because these are real people who have drunk the ‘Kool-Aid’.”

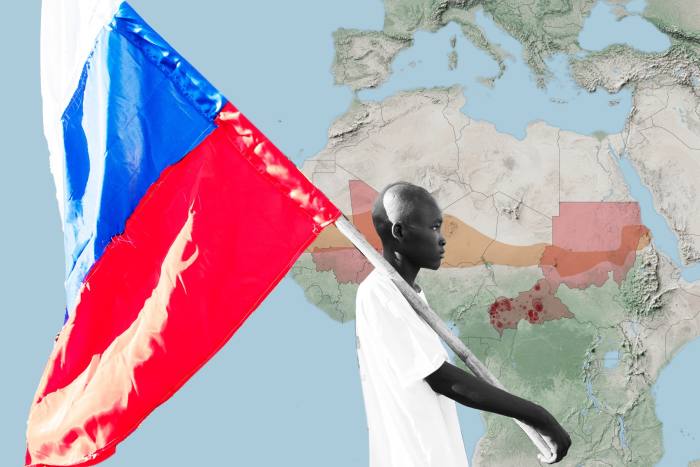

Beyond Mali, where the mercenaries arrived last year at the invitation of the government, Russia’s worldview receives a sympathetic hearing in much of the continent despite its invasion of Ukraine — a breach of international law that 26 African countries refused to condemn at the UN.

Russia is aided by memories of the financial and military support the Soviet Union gave to African liberation struggles, making Moscow still welcome in much of the continent.

“The Soviet Union was created to overthrow tsarism and the old feudal order. That’s what [Russian president Vladimir] Putin represents to many people,” said Trevor Manuel, a former finance minister of South Africa, which has refrained from condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“The Kremlin views Africa as an increasingly important power-projection theatre,” said Samuel Ramani, author of a forthcoming book on Russia’s involvement in Africa. “They work with existing autocrats and create an authoritarian stability model which they equate with anti-neocolonialism.”

Russia in Africa

This is the second part in a series on Russia in Africa, which also covers how Moscow is opening what some call a “second front” and control of resources

Read part 1: How Moscow bought a new sphere of influence on the cheap

The Central African Republic is one country where Moscow is exerting control of the narrative. Russia became involved five years ago when the Bangui government turned to Moscow to help defeat rebels who were besieging the capital.

“It’s worse than mere propaganda right now — they’re shaping Central African domestic politics,” said a western diplomat in CAR. “The propaganda is orchestrated [from Moscow] and it’s very well done.”

In Mali, meanwhile, Russia has successfully clouded the debate about the impact of its intervention. A probe by Human Rights Watch found that weeks after they arrived, mercenaries operating alongside Malian troops executed an estimated 300 men in the town of Moura, including suspected jihadis and sympathisers.

Cameron Hudson, a former CIA official now with the Center for Strategic and International Studies think-tank, said that in francophone Africa, pro-Russian sentiment was the flipside of strong anti-French feelings.

“In Mali, they were describing a relationship in which the French were running roughshod over their Malian partners, not sharing intelligence, aggravating tribal, regional and cultural divides,” he said of a nine-year military intervention that ended with France’s departure last year.

If some pro-Russian narratives emerged organically, say analysts, others were manipulated or amplified by Russian groups, some of them linked to Wagner boss Yevgeny Prigozhin, a Putin ally.

Meta, parent company of Facebook, has a team dedicated to unearthing “co-ordinated influence operations” that use fake accounts to build the illusion of widely held beliefs.

Since Meta began hunting for such operations in 2017, it said it had found about 150 networks worldwide, of which 30 targeted Africa. The high proportion underscores what analysts and diplomats say is Moscow’s view of the continent — with 54 UN votes, huge reserves of strategic metals and the world’s fastest growing population — as central in its battle to control the global narrative.

Meta executives said several of the efforts pushing a particular line while concealing their true provenance were Prigozhin-linked.

In this narrative, rather than being an aggressive imperial power, Russia was a champion of the underdog against US-led hegemony. Putin pushed that line in his September speech to mark the annexation of four regions of Ukraine in which he cast the west as “racists” who treated poorer countries in Africa and elsewhere as “vassals”.

One influence operation discovered by Meta targeted Sudan. In a report from 2021, the company said it had removed a network operated by local Sudanese nationals on behalf of individuals linked to the Russian Internet Research Agency, a Saint Petersburg-based troll farm financed by Prigozhin, according to US authorities. The “foreign interference” network included 83 Facebook accounts and 49 on Instagram, with a total following of almost 500,000 users.

They spread pro-Russian and anti-western messages at a time of high volatility following the overthrow of Omar al-Bashir’s dictatorship. The content praised Russia, portrayed some leaders as pawns of the US and pushed the benefits of a proposed new Russian military base at Port Sudan.

The accounts also amplified Russian largesse. The amount of aid provided by Moscow is tiny compared with that given by many western countries, but the online content featured images of aid emblazoned with the Russian flag and Arabic text proclaiming “From Russia with love” and “Courtesy of Yevgeny Prigozhin”. The stories were picked up by Sudan’s news agency, Suna, and distributed around the country.

Tessa Knight, who investigates disinformation networks at the DFRLab, said Russian groups preferred to work with local content because it was harder to generate convincing material in a foreign language. Some pro-Russia material in Sudan appeared in error-riddled Arabic that looked as though it had been put through Google Translate, she added.

The disinformation networks are also accused of spreading their own anti-western content. Last year, France identified what it said was an attempt to stage a fake “massacre” in Mali. It released footage of soldiers it identified as belonging to Wagner burying corpses in the sand outside a military base recent vacated by French troops. France said the footage was to be shared online and its soldiers held responsible.

DFRLab said the footage showed discolouration in the sand after the French had gone, adding: “Whatever happened [at the base], happened after [the French] vacated.”

Russia’s newfound influence in the CAR meant anyone in Bangui who opposed Moscow was quickly shut down, said Roland Marchal, a French expert on the region at Sciences Po, the French university. Critics of the pro-Russia stance had been abducted, while President Faustin-Archange Touadéra was effectively held “prisoner” by the Wagner guards sent to protect him, Marchal said.

But Blaise Didacien Kossimatchi, a pro-Moscow commentator in CAR who has denied western intelligence claims that he is bankrolled by Russia, said: “People talk about Russians killing people and not respecting human rights — that’s nonsense.” Members of his 45,000-strong Plateforme de la Galaxie Nationale Béafrika political grouping sometimes wear T-shirts emblazoned with the words “Je suis Wagner”, meaning “I am Wagner”.

Moscow also funds the CAR’s Radio Lengo Songo, according to one of the station’s editors. Internet penetration is low in the country and radio remains influential. “It’s the Russian Federation that pays,” the editor said, speaking on condition of anonymity. “A good part of our financing comes from the embassy. They have a delegate who comes and checks on the content.”

While Russian attempts to spread its version of events in Mali are more recent, they have proved effective. Kamissa Camara, a minister in the Malian government that was ousted in a 2020 coup, said the propaganda fed a distorted view that France let Mali down and that Russia had come to its rescue.

“If France had not come in to save Mali from the terrorist threat, half the country would have fallen into the hands of jihadis. It’s just a fact,” Camara said.

But for Diabaté, French meddling proved a failure. “The only country that truly fights against terrorists in the world today is Russia,” he said. Rebuking critics of Mali’s new direction, he added: “I want western countries to stop harassing us about Wagner. They should stop disrespecting Africans.”

[ad_2]

Source link