[ad_1]

Science is often portrayed as a meritocracy in which one’s ideas and abilities matter more than anything else. But Nature’s 2022 survey of PhD and master’s students points to an unpleasant reality: those who identify as members of minority ethnic groups face a greater share of discrimination and indignities than do students who aren’t in those groups.

Obstacle race: the barriers facing graduates who study abroad

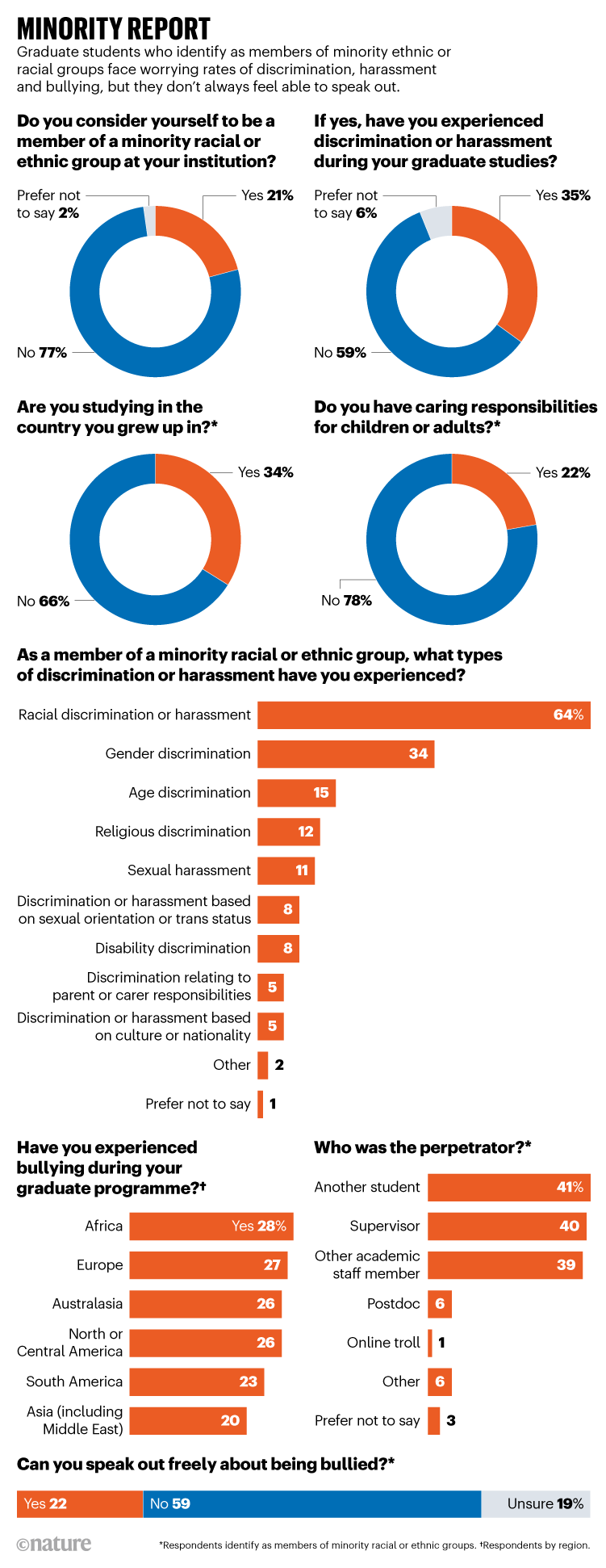

The survey drew 3,253 self-selected responses from around the world (see ‘Nature’s graduate student survey’). Twenty-one per cent of respondents identify as members of minority racial or ethnic groups in the countries where they currently live. Through survey responses and free-text comments, they describe mistreatment and struggles that go beyond the typical challenges of graduate school — from structural racism in institutions to microaggressions committed by peers.

Nature’s previous surveys polled respondents about their experiences of discrimination and bias. This year’s survey was the first to examine those experiences more deeply.

Some 35% of respondents from minority racial or ethnic groups say that they have experienced discrimination or harassment during their current programme (see ‘Minority report’). That’s more than twice the rate reported by respondents who do not identify as members of those groups (15%). “The sheer amount of sexism and racism that I’ve faced as I pursue my doctoral degree is beyond anything I could have imagined,” writes a PhD student in the United States. Moreover, 26% of students from under-represented groups and 15% of students who are not from such groups say that they have experienced bullying during their programme.

A vocal group of respondents shared their personal experiences of racism in the survey’s free-text section. A master’s student in the United States wrote: “Supervisors do not care about how their trainees face racism, homophobia, sexism and other barriers, but will pretend they do by using pronouns and rainbow flags.” A PhD student in Germany commented: “My supervisor was racist towards me and made my life a living hell.” She went on to say that when she reported the behaviour to her institution, she was told that administrators were already aware of issues with that particular supervisor.

When asked what they wish they had known before starting graduate school, a master’s student from Africa studying in China wrote “I wish l had known how racist and abusive the dean and management are.” A PhD student in the United States said, “I wish I’d known how prevalent and ‘normal’ racism and sexism is in academia. I probably would have angered less people and had a better strategy of survival if I knew this culture was the norm.”

Another PhD student in the United States wrote that racist comments and attitudes can “take a toll on mental health”. In the survey, students from under-represented groups are more likely, at 38%, to report receiving help for depression or anxiety caused by their graduate studies than are students who are not from those groups (32%).

Evolutionary biologist Kevin Lala.Credit: Kevin Lala

Despite a rise in discussions about equality and diversity on campuses and in the workplace, racism seems to be as prevalent as ever in academia and beyond, says Kevin Lala, an evolutionary biologist at the University of St Andrew’s, UK. (Lala, whose father is from India, has for decades used the anglicized surname Laland. Lala now uses his father’s actual surname in a nod to his heritage.) “In the UK, there have been trends for the worse, not for the better, in recent years,” he says. “Many of our undergraduate and graduate students have experienced racial harassment.”

Lala, who discussed racism in academia in a Nature column in 2020 (see Nature 584, 653–654; 2020), says that racist slurs and other overt acts tend to be more common off campus than in university labs and classrooms. “Universities are relatively benign environments compared with the rest of the world,” he says. Despite this, he says, racism remains deeply woven into academia and institutions, especially when it comes to hiring, promotion and student retention.

According to the US National Science Foundation, members of minority ethnic and racial groups held less than 10% of doctorate-level positions in science, engineering and health in 2019, despite comprising more than 30% of the US population (see go.nature.com/3grd4v3). Similarly, a UK Royal Society report estimates that Black scholars accounted for 1.7% of all academic positions in science, technology, engineering and mathematics in the United Kingdom in 2019 (see go.nature.com/3ahyvea), although the Black population in England and Wales for that year was estimated by the Office for National Statistics at 3.5%. Anecdotally, Black scholars in the United Kingdom have reported that they are the only Black person in their department or institution, and sometimes in their field.

Collection: Diversity and scientific careers

Lala says that those who are members of under-represented groups clearly have a more difficult time reaching the highest levels of UK academia. “People of colour are pretty well represented across tertiary education in general,” he says. “But when you look at the top universities and the higher echelons of universities, they are highly under-represented.” He notes that many hiring committees lack members of colour, and that job advertisements aren’t necessarily reaching diverse communities. “There are subtle things that bias the landscape against minority groups,” he says.

Nature interviewed three survey respondents who say they have experienced racism in their training — an African American PhD student in the United States, a PhD student in Spain who is from India, and a Brazilian PhD student in Canada. All three spoke on the condition of anonymity.

Microaggressions

The US PhD student says that he heard racially tinged comments from supervisors and fellow students during his undergraduate training at a university in the southeastern part of the country. “I was frequently the only Black person in my upper-level biology courses,” he says. “There were a lot of microaggressions. People would call me ‘articulate’, which felt racially motivated. I speak normal English.” During his time at the university, two incoming first-year students were banned from campus after sharing blatantly racist posts on social media. In the aftermath, he and a couple of other Black students met a department head to discuss their concerns. “We talked about being fearful to speak out in class,” he says. “He was very dismissive. He wasn’t listening to what we were saying.”

Racism: Overcoming science’s toxic legacy

He says that he hasn’t sensed any racism during his graduate programme at a university in the Midwest. The institution, he says, recently hired a new dean for graduate diversity and inclusion. In another positive step, there is now a mental-health counsellor who exclusively serves graduate students. “The university is more responsive to the issues that we have,” he says, “and they’re making the experience better as things go along.”

Nevertheless, he says, he has some questions about the university’s recruitment strategy for students. His adviser sits on the admissions committee, so he’s had a chance to meet and interact with applicants. The university, he says, could be more assertive in attracting and retaining students from under-represented groups. “I see a lot of minority applicants, but they don’t come out the other side and actually enrol.”

‘Indian way of working’

The Indian student in Spain says that she needs regular counselling sessions to help her cope with the stress and anxiety of dealing with her supervisor. She says the supervisor is harsh to everyone in the lab, not just to students from under-represented groups. But, says the student, the supervisor does save some of her most biting comments for people from other countries. One morning, the student says, she came in 15 minutes late after putting in extra hours the night before. “My supervisor got really bossy with me and asked ‘Is that the Indian way of working?’ I was really shocked. She’s judging me based on the country that I’m from, and that’s not correct.”

Other researchers and students at the institution are welcoming and easy to work with, she says. “Everyone is respectful of one another.”

Decolonizing science toolkit

The Brazilian student in Canada had struggles of her own at the beginning of her PhD programme. She says that her supervisor, who was from another country herself, frequently belittled her English and scientific skills. “At first I thought she was just trying to get the best out of me, but I noticed she was treating me differently to other students in the lab,” she says. “She said it was a mistake to accept me as a PhD student because students from Brazil can’t achieve the same levels as students from Canada. Because the education in my country is really poor.”

Feeling unwelcome and unsupported, the student reached out to the academic affairs office, where she was advised that she could either convert her PhD to a master’s programme and graduate early, or change labs and supervisors.

She decided to change labs, and says that she now feels much more at ease. All the same, she wishes there was a way for supervisors to be held accountable for mistreatment. If they don’t face consequences for unfair and discriminatory behaviour, she says, “it’s going to keep happening.”

[ad_2]

Source link