[ad_1]

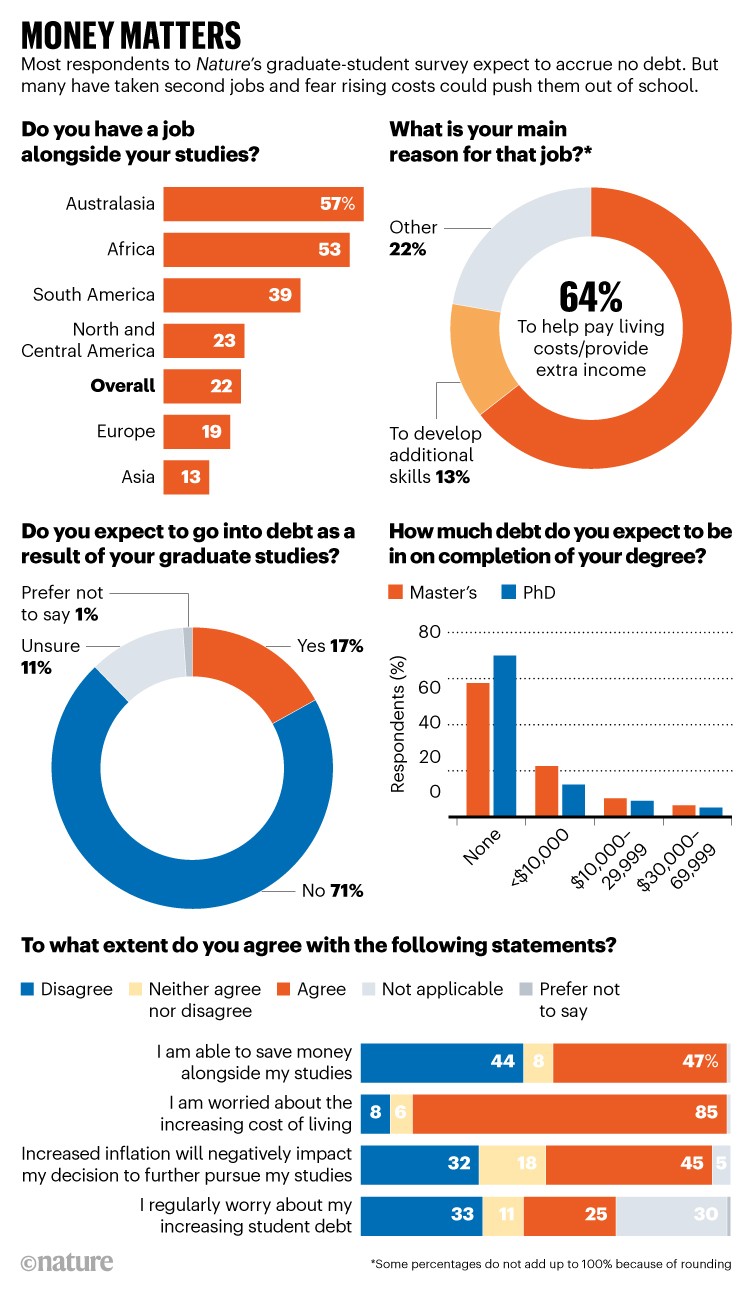

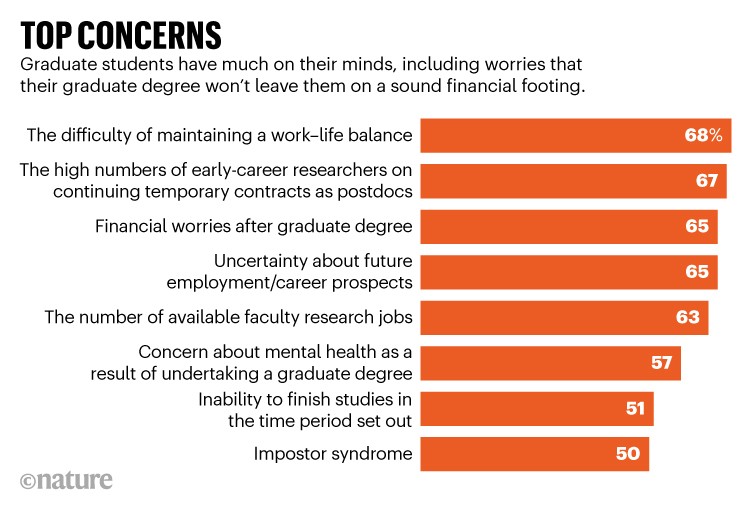

Eighty-five per cent of respondents to Nature’s 2022 survey of graduate students worry about having enough money to buy food and pay rent and other expenses, a testament to one of the most urgent issues worldwide in higher education. This growing financial stress threatens to derail some promising careers. Nearly half (45%) of respondents agree that the rising costs of living could prompt them to quit their graduate programme.

The questionnaire, Nature’s first survey of graduate students to include master’s as well as PhD students, drew more than 3,200 responses from around the world. In answers and free-text comments (See ‘Money is a really big issue’), students told of the struggles of continuing their education while trying to make ends meet. Follow-up interviews with respondents in places including Bengaluru, India, and Boston, Massachusetts, added more details to a global crisis that is unlikely to subside soon. “It looks like it’s only going to get worse,” says Nathan Garland, a mathematician at Griffith University in Brisbane, Australia, who reviewed the survey responses. “There’s no handbrake on the situation at the moment.”

Financial concerns are especially prevalent in North America, where more than three-quarters (76%) of respondents list ‘overall cost of living’ as one of the most challenging aspects of getting a degree. Respondents in North America are nearly unanimous in their worries: 95% agreed or strongly agreed that the rising cost of living is a concern. (In September 2022, the year-on-year inflation rate in the United States was 8.2%. In the United Kingdom, the consumer price index rose 10.1% in the preceding 12 months.) A biology PhD student in the United States wrote in the comment section: “It’s hard to focus on researching, teaching, mentorship, writing papers, applying for grants, when you don’t even have enough money for food.”

Money woes are weighing on Carly Golden, a second-year PhD student at Boston University in Massachusetts, an institution in one of the most expensive cities in the United States. She receives a stipend of around US$40,000 a year, which she says falls far short of the cost of living. “It’s close to poverty [level] in Boston,” she says of the stipend. (According to the living-wage calculator from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, a living wage for a single adult in Boston is nearly $47,000 a year.) “I spend more than 60% of my stipend on rent,” she says. Golden could potentially save money by living with room-mates, but says that she needs space and quiet to be able to study properly. She could save on rent by moving to a less-expensive suburban area, but she already has an hour-long commute to her laboratory. “If I could reapply to a programme, I probably would do so in a state that was more affordable,” she says.

In India, graduate students often end up living in areas where costs are the highest, says Amit Kurien, a social ecologist who took the survey shortly after receiving his PhD at the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment in Bengaluru. “The good universities are in metropolitan areas, right in the hustle and bustle,” he says. He notes that Bengaluru, a hub for information technology, has a burgeoning population of young professionals with decent incomes who live very differently from the graduate students who are simply trying to get by day to day. Kurien says he was making little more than $4,000 per year midway through his PhD. “It was a pittance.” He adds that he was able to get by thanks in part to support from his parents, a luxury that not everyone has.

Second jobs

In Australia, pretty much the only students who can manage comfortably either get help from their families or have a partner with a good job, says Garland, who co-authored a June 2022 piece in The Conversation that described the financial distress of graduate students in that country (see go.nature.com/3fcqvjj) .

Many graduate students take on extra teaching duties to help pay the bills. “Universities can use that cheaper labour rather than hiring permanent staff members,” Garland says. He calculates that graduate-student stipends in Australia equate to about two-thirds of the national minimum wage, forcing many students to look beyond the university for extra income. “Some are driving Ubers or working at a pizza shop,” he says.

Nearly one out of four respondents to the Nature survey say that they have a second job (see ‘Money matters’), a sign of how far students are willing to go to stay in their graduate programme. Such jobs are especially common for master’s students (31%), probably because their stipends are often smaller than those of PhD students. And although many doctoral students have contracts that prohibit them from taking outside jobs (prohibitions that they might or might not actually follow), some master’s students have more flexibility.

Ethan Solomon, a second-year master’s student at the University of Toronto in Canada, says there’s nothing in his contract that stops him from having a job outside his studies. While other students are driving for ride-sharing companies or waiting at tables, Solomon earns extra money by working as a ‘brand ambassador’, which means he promotes products and hands out T-shirts and other promotional items at concerts, jazz festivals and other events — including the May 2022 edition of the JUNOs, a prestigious award ceremony for Canadian musicians. The events generally take place at weekends, which makes it possible for Solomon to fit them in. “It doesn’t interfere with my lab work and I’m still progressing, so there’s no issue there,” he says.

Solomon says that he’s planning to end his formal education after getting his master’s degree, largely because he can’t see himself coping with poverty-level wages for another four or five years to earn a PhD. In the survey, just over one-half of master’s students said that they planned to continue to a PhD programme. (Nature will explore the experiences of master’s students more fully in a future story.)

Graduate debt

Almost one-fifth of respondents said that they expected to accrue debt while studying (see ‘Top concerns’), some on the scale of tens of thousands of dollars. Another 11% were unsure whether they could finish their programme without going into the red. Overall, 71% said that they didn’t expect to go into debt, although this group is likely to include many students who enjoy support from family or partners. Golden says that she would probably have accrued debt without the research job she had before starting graduate school. “If I didn’t have a healthy savings from my four years working in industry, then I would have to take out loans,” she says.

Notably, 33% of respondents with caring responsibilities expected to go into debt during their studies. Students with families at home are especially likely to fall into debt, says Jayson Lusk, an economist at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana. In November 2020, Lusk helped to conduct a survey that collected more than 1,400 responses from graduate students at the university. In that survey, students without dependants had median savings of more than $1,100 a year, but students with dependants ran a median annual deficit of more than $20,000.

The Purdue survey found that students who expected to make more in their eventual careers were less likely to save money while studying. “Some of them are doing it as an investment,” Lusk says. “They’re willing to take out loans to make more money in the future.”

Lusk notes that most graduate students at Purdue are paid as half-time employees through research/teaching assistantships. In August 2022, that amounted to a minimum annual salary of $24,124. He adds that those students also typically receive a tuition waiver, plus benefits such as health insurance and paid holidays. “You don’t get rich in graduate school,” he says. “But I don’t think it’s exploitive,” he adds.

Carly Golden, a PhD student at Boston University in Massachusetts, says that she spends more than 60% of her stipend on rent.Credit: Carly Golden

Small steps

Some institutions are taking steps to help students keep up with rising costs. Amy Dashwood, a second-year PhD student who works at the Babraham Institute, a life-sciences research centre affiliated with the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, saw her pay increase after she took the survey. The institute pledged to ensure that, from 1 October, no student would earn less than £19,000 (US$21,700) per year. In her case, that meant an extra £250 each month on top of her usual funding, which comes from the Medical Research Council, a division of United Kingdom Research and Innovation (UKRI), the nation’s largest research funder. Also on 1 October, the UKRI raised the minimum student stipend to £17,668, an increase of more than £2,000 per year.

Dashwood says that the extra funding will relieve much of the financial stress of graduate courses. “This will take a lot of weight off my shoulders and allow me to concentrate better on my studies,” she says. “This should mean I can comfortably buy my groceries and hopefully won’t have to constantly be checking my bank account.” She adds, however, that she expects to continue a frugal lifestyle that includes sharing a house with two people, getting by with basic groceries and rarely going out. She can’t afford to hang out with friends and go away on holiday, she says, the sorts of activities that would help her to relax and take her mind off her work. “It takes a toll on your mental health.”

In Australia, it would take legislative action, or perhaps an emergency declaration from the education minister, to substantially improve federal support for graduate students, Garland says. He sees such a declaration as unlikely, even though graduate-student finances are clearly an emergency. “Hopefully, at some point it gets better,” he says. “But it won’t get better if we don’t call attention to it.”

[ad_2]

Source link