[ad_1]

As Communist party boss in Shanghai, Li Qiang’s signature business coup was persuading Tesla founder Elon Musk to build the US electric-car maker’s first overseas factory in the Chinese megacity.

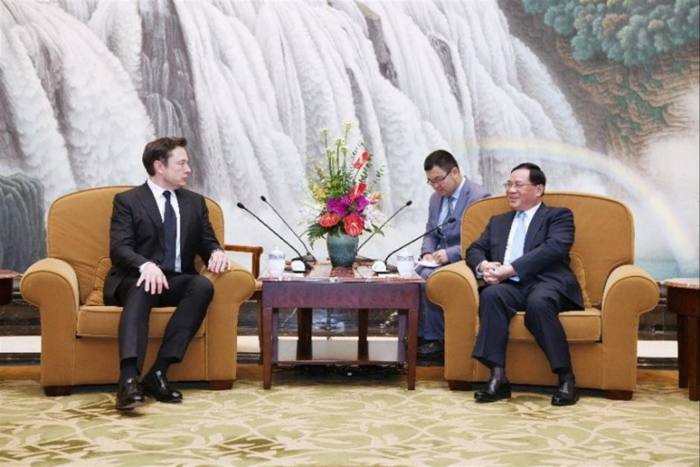

At the signing with Musk in 2018, the man who would one day become President Xi Jinping’s number two spoke glowingly about creating “favourable” conditions for commerce, while a rainbow on a giant painting behind them created a halo over the rising party star.

But Li’s pro-business credentials are about to be sorely tested. China’s rubber-stamp parliament confirmed him as premier and head of the State Council, or the cabinet, on Saturday, with 2,936 votes in favour, three against and eight abstentions. After signing his appointment letter, Li stood to give Xi a fervent handshake. Rarely has an incoming premier faced such a daunting in-tray.

Li and his economic team will need to devise a new growth strategy to replace China’s flagging debt-fuelled model while overseeing a sweeping restructuring of the state, including the financial regulators, announced this week.

Perhaps harder still, he will have to manage his boss. Xi’s sudden policy changes in recent years on issues ranging from cracking down on internet companies to Covid-19 controls have unsettled investors, analysts said.

“He inherits a job that has so many headwinds, starting with the real estate crisis, the debt burden, US sanctions, the ageing of China and the sentiment being down,” said Jörg Wuttke, head of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China. “The guy has his work cut out for him and the low-hanging fruit has been plucked by his predecessors.”

As with many in Xi’s inner circle, Li owes his rapid rise to a close association with the Chinese leader when they both served in provincial jobs. An agricultural engineer, Li worked for Xi in a secretarial role when the latter was governor of Li’s native Zhejiang, one of China’s rich eastern coastal provinces, in the mid-2000s.

After Xi became president in 2012, Li became Zhejiang governor himself, then the communist boss of nearby Jiangsu province and in 2017, Shanghai party secretary.

During these years, he was regularly pictured rubbing shoulders with top businesspeople, particularly Jack Ma, founder of Zhejiang-based internet group Alibaba, who has largely disappeared from public view since Xi’s internet crackdown.

He even wrote the prologue to a book by Wang Jian, chair of the Alibaba Group’s technology committee. “Jack Ma and Wang Jian are both my favourite people to chat with,” Li wrote when he was governor of Zhejiang.

Li is “uniquely positioned to lead the new administration” given his experience in heading “the most developed regional economies in China with critical contributions from private, foreign-invested and state-owned enterprises”, said Eric Zheng, head of the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai.

Aside from the Tesla deal, Li is also credited with the opening of a new Nasdaq-style stock market in Shanghai.

But Li’s record was blemished last year after he implemented one of the most stringent and, in the eyes of many, mismanaged Covid lockdowns in China. Residents of the nation’s wealthiest city struggled to get enough to eat.

Yet he has refused to accede to criticism of the handling of the outbreak, later saying “we . . . won the battle to defend Shanghai”.

The Shanghai lockdown has been widely interpreted as a display of fealty to Xi, who had repeatedly emphasised the importance of the zero-Covid strategy before the policy was abandoned in December.

“The Shanghai lockdown showed that when push comes to shove, Li Qiang will do whatever Xi Jinping wants,” said Neil Thomas, a China analyst who this month will join the Asia Society Policy Institute’s Centre for China Analysis in Washington.

By contrast, while Li Qiang was paralysing China’s financial hub, his predecessor, outgoing Premier Li Keqiang, was sounding the alarm over the economic impact of the pandemic on a video call with tens of thousands of officials. Li Keqiang, an economist by profession, did not refer explicitly to Xi’s zero-Covid policy, but his comments hinted at the internal difficulties of balancing the approach with economic growth.

Despite occasional attempts to be more assertive, Li Keqiang was seen as largely stymied by Xi, who viewed him as a one-time rival hailing from a different political faction.

As a trusted longtime adviser, Li Qiang might have greater access to the president’s ear, analysts said. Some suggested that, based on his recent speeches, Li Qiang wants to pursue similar policies to his predecessor, including controlling debt and reorienting the economy towards consumption.

“Politically he will give credit to Xi Jinping in terms of the achievements of the past five years, but in terms of policy orientation he is taking his cue from Li Keqiang,” said Bo Zhiyue, founder of the Bo Zhiyue China Institute, a consulting firm.

While more details of Li Qiang’s economic programme are expected to be revealed on Monday, when he gives his first remarks as premier, many observers expect Chinese policymakers to be restrained in the coming year as growth rebounds from last year’s Covid controls.

“It looks like policymakers are hoping and expecting that this year’s growth will be coming from organic sources . . . and they don’t really plan to drive up this growth with very expansionary policy,” said Louis Kuijs, chief Asia economist at S&P Global Ratings.

But in the long run, few expect Li to be able to resurrect the strong reformist premierships of the past, such as those of Wen Jiabao under Xi’s predecessor Hu Jintao, or Zhu Rongji under the late president Jiang Zemin.

A newcomer to the national stage, Li Qiang will need to build alliances in Beijing. But Xi, ever careful about his position at the head of the party, is expected to keep Li on a tight rein, analysts said.

“The potential for unpredictability is going to remain a chronic risk with Xi in charge and especially with a leadership team comprised entirely of his allies,” said Thomas. “Xi’s policies will be implemented for good or bad under Li Qiang.”

Additional reporting by Nian Liu, Xinning Liu and Ryan McMorrow in Beijing

[ad_2]

Source link