Gardens are not only places for plants. They are also places for events. Both come and go, but events have the longer afterlife, passed on by participants and collective memories. I doubt if you remember the dahlias you left in the ground before winter weather killed them there in 2018. I bet you remember the significant wedding or birthday party you gave in the garden, even 20 years ago. Events pass into photos and sometimes into print.

On the last Saturday in June I moved between two very different events, held simultaneously in two very different gardens, one in Oxford, one near Cambridge. I fled from the event in my Oxford college, one that traumatises me every three years. In its gardens the undergraduates put on a Commemoration Ball: 1,600 people are on site until dawn, the women in long dresses, the men in white tie and tails. How idyllic, you may be thinking, but I am a scarred veteran.

This year’s ball was the 14th during my role of running the College garden. After a steep learning curve in the 1980s, we now have rules and a prescribed procedure: no guard dogs to keep out intruders, no use of half of the available lawns, no bean bags, no bumper cars and, after last year, cups, not glasses, for the opening round of champagne.

We ban glasses because they are abandoned and smashed into fragments by passers-by in the night. We ban guard dogs partly because they fail to discriminate between gate-crashers and absent-minded professors. In the mid-1980s, they attacked one who had forgotten the occasion and tried to enter the College by a back gate. He wanted to find the packet of cigarettes he had left in his room the night before.

I have two top tips for gardeners who are holding summer parties for younger dancers. One is to ban bean bags: they burst when tired or when amorous couples fall on to them. They scatter white polystyrene beans that are impossible to hoover away.

The other tip is to cover the areas for dancing and the main approaches to them with wide runs of thinly backed cheap carpeting, nailed down shortly before the event’s beginning. It is a lawn-saver, especially if it is rolled away promptly after the party’s finale and the grass underneath is watered immediately.

We began our use of carpeting with a bright shade of red, which appealed to the celebrity aspirations of young millennial guests. In 2018 the organisers changed some of it to eco-signalling green. This year, one part was a bright purple-blue, the other a muted red. The colours were governed by availability, not by political messaging.

I never attend these balls. This year I escaped towards Cambridge for a garden event with a very different resonance. In nearby Godmanchester, Farm Hall is a fine Georgian house, dating from 1746 and once briefly owned by the National Trust. Since 1979, it has been landscaped and loved by its current owner, Marcial Echenique. He is emeritus professor of land use and transport studies and a former head of the department of architecture at Cambridge. He has designed whole cities all over the world, but he has preserved Farm Hall as a green landscape. Instead of a city, he has planted trees, cherished its ha-ha and improved its old walled garden.

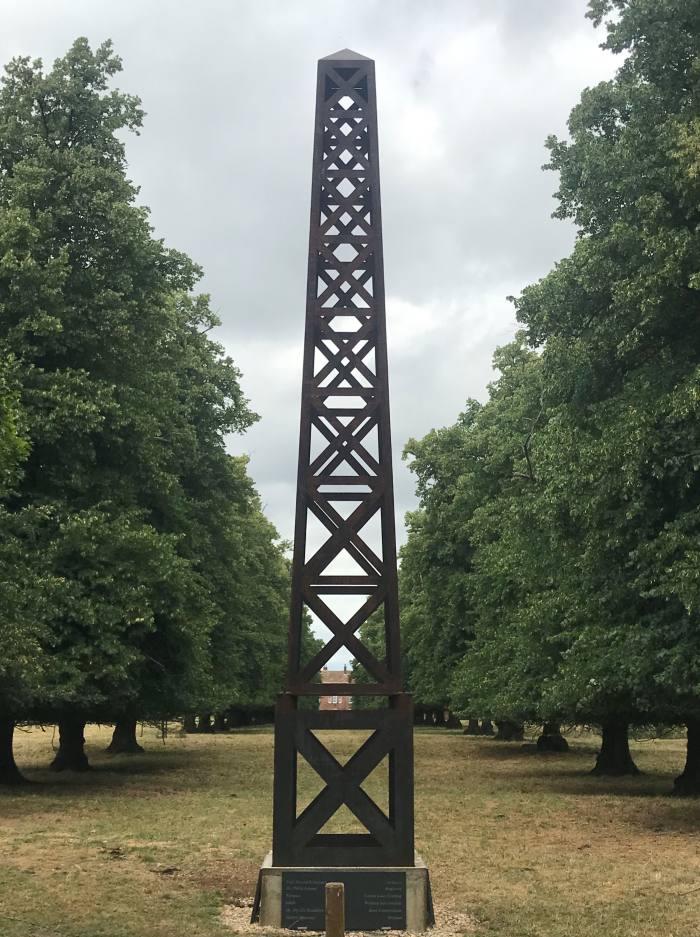

At the end of a superb avenue of lime trees he has just designed an obelisk, calibrating it to the height of the house in the distance. Like the “Angel of the North” sculpture by Antony Gormley, it is made of weather-resistant steel, which will slowly turn rust-brown. It honours the remarkable interns who lived at Farm Hall between July 1945 and January 1946. They were 10 nuclear physicists, captured under Operation Epsilon during the Allied advance into Germany. They were taken from their research centres and reassembled at the Hall.

Residents of Godmanchester, friends and fugitives like me gathered for the unveiling of the commemorative plaques. A historian, Roger Leivers, introduced us to Farm Hall in wartime, first as a centre for training spies and sending them back into their Nazi-occupied homelands, then as a centre for detaining captured physicists.

While BBC weather predicted rain over Oxford, Sir Richard Dearlove, former head of MI6, mounted the platform and gave a heartfelt endorsement of the commemoration. The obelisk is one of only two memorials, he told us, that commemorate espionage in Britain, the other being indoors at a college for spies whose identity he could not reveal. I am pretty sure it is not New College, Oxford.

While at the Hall, the German physicists played ball in the garden, chatted in quiet corners and enjoyed good food. One of them even jumped over the barrier fencing and met women by night in Godmanchester: he would surely have gatecrashed our Commemoration Ball. The interns at the Hall had no idea that people like Dearlove had bugged every room and were poring over transcripts of their conversations for clues to their understanding of a nuclear bomb.

On the way to the obelisk, I admired a garden with a pond, tall lavender, lines of Verbena bonariensis and elegant arches covered with the pink-flowered rose Minnehaha, a rambler that came to the market in 1865. I was treading in some legendary footsteps. Long before Echenique devised this planting, the garden was frequented by Heisenberg, inventor of the uncertainty principle. Until recently, he has been a genius of uncertain repute in the tale of the nuclear bomb.

In his admired 1998 play, Copenhagen , Michael Frayn left audiences uncertain whether Heisenberg had deliberately diverted Nazi interest away from such a weapon. In the play, as in life, Heisenberg visited the great Niels Bohr in Copenhagen, his friend and fellow physicist who took him to be saying that he was indeed engaged in such a venture. However, letters between the two have been published since 2002 and are considered to show that Bohr had misunderstood what Heisenberg said: he was willing to work on a nuclear reactor, but not on a bomb. A plaque on the new garden obelisk commemorates the German physicists for limiting their work to reactors.

Whether Heisenberg and others already knew enough to devise a bomb is a disputed subject. When an atomic bomb was used on Japan, certainly the news appalled Farm Hall’s interns. In his fine drawing room on the Hall’s first floor, Echenique showed me a central boss in the ceiling and explained that it was where Otto Hahn, winner of a Nobel Prize for chemistry in 1944, had tried to hang himself after hearing the news of Hiroshima. He felt guilty at what nuclear knowledge had done.

Commemoration balls in Oxford owe their name to Commemoration Week, in which they are held. After the end of the summer term, it contains events to commemorate former benefactors. A commemoration of spies and physicists may seem very different, but as the rain failed to arrive, I reflected that they might have more in common.

In front of my roses and silver-grey teucrium in the College, Saturday’s young partygoers included scholars in nuclear physics, perhaps with transformative careers ahead. They might also have included some future spies, one day to be pillars of MI6. Their dancing has done no horticultural damage, but I have no plans, as yet, for an obelisk in their honour.

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @FTProperty on Twitter or @ft_houseandhome on Instagram