[ad_1]

Four shows this month deal with personal identity — how it’s formed by the past and how we are forced to deal with it, one way or another. But the ways that the four artists explore it are very different.

Chicago and Atlanta photographer Thomas Dorsey is widely known for his at-home portrait photographs of African American families, including Andrew Young’s. Curated by Andi McKenzie, A Very Incomplete Self-Portrait: Tom Dorsey’s Chicago Portfolio, at the Michael C. Carlos Museum through July 16, is the first appearance of a singular body of work Dorsey has only recently allowed to be publicly recognized.

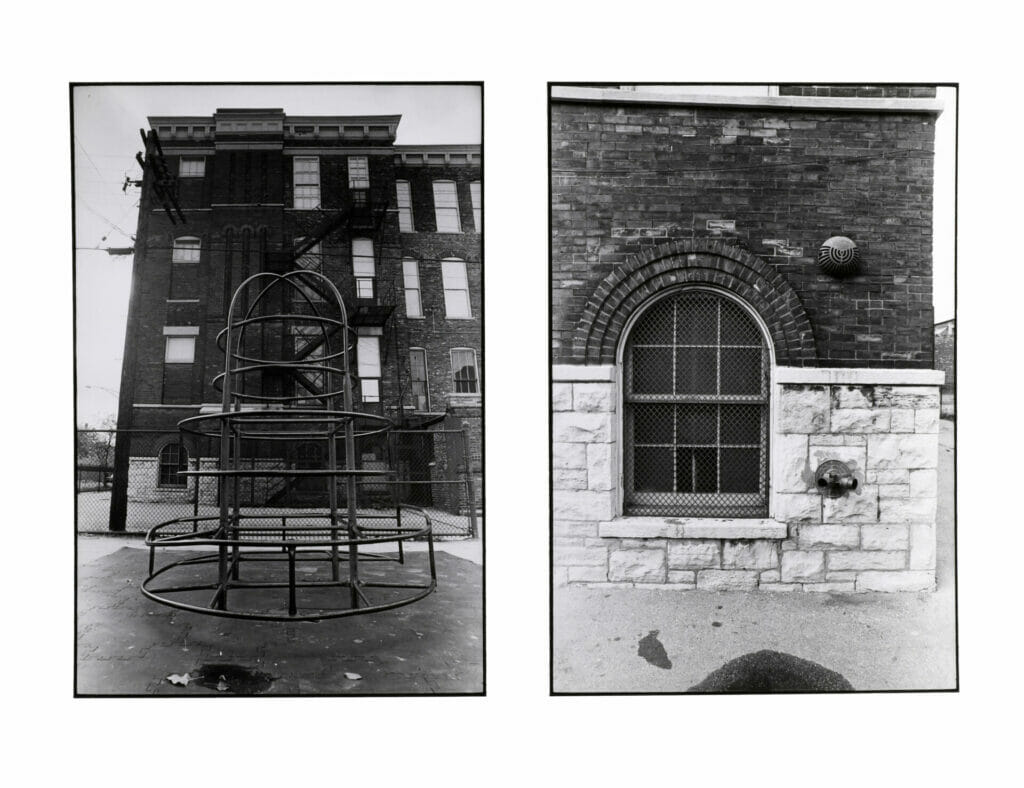

In 1971, Dorsey undertook a reflective re-examination, through carefully composed black and white photographs, of the neighborhood where he grew up. Their more subtle meanings are amplified by the pairings of photos in the one-of-a-kind portfolio he has given to the Carlos.

Some of the socially revelatory pairings are fairly evident, as in the photographs of the modest-looking stores on the middle class side of Fulton Street and the even more humble architecture of a store on the other side of Fulton, the street that marked the boundary of Dorsey’s neighborhood.

An audio guide accessible through QR code explains some of the hidden realities, as when Dorsey remarks that the school, documented through innovatively composed photographs of fire escapes or playground equipment, always reminded him of a prison.

On March 23 at 7 p.m., in the Jones Room of Emory University’s Woodruff Library, Dorsey will engage in conversation with another legendary African American photographer, Jim Alexander.

At Hammonds House Museum through April 2, Tokie Rome-Taylor’s Insight: Body as Artifact, Archive and Memory, curated by Nitzanah Griffin, is a deep dive into the material and imaginative heritage of the African diaspora.

But describing it in those academic terms loses the sensory impact of these photographs. African American children are clad in gorgeous vintage costumes, surrounded by symbolic tufts of cotton or wearing masks in photographs with titles referring to “haints” or to Robert Farris Thompson’s famous book Flash of the Spirit.

Despite oblique scholarly references, the painterly qualities of lushly printed cyanotypes and color photographs encrusted with gold mica ensure that immediate emotional involvement outweighs theory.

However, the theory is appropriate and sensitively applied. Curator Griffin has done an excellent job of elucidating the deeper meanings that Rome-Taylor has encoded in photographs that less attentive viewers might see only as objects of aesthetic enjoyment.

The photographs, rich in themselves, grow even more richly nuanced when we read such things as a wall label telling the story of an African American family whose ancestors were able to keep ownership of 128 acres of land “during some of the most brutal times in the south.” That story explains the objects in the basket being held by the subject of Olivia’s Legacy of Pine, Feathers, and Soil.

In addition to its extraordinary range of photographic techniques, the exhibition includes a room of installation art and a sculptural Conjure Woman. Its core message is also summed up in Rome-Taylor’s self-published book, Reclamation, available at Hammonds House or through her website.

Hannah Ehrlich’s clearing: a fertile exhale, at Swan Coach House Gallery through March 23, is a stunning textile installation curated by Makeda Lewis.

Ehrlich’s technique of overlaying thick paint on combinations of macramé, crocheting and sewing results in immense, complicated entanglements. Ehrlich describes it as a way of studying the unconscious impact of “traumatic events that have fractured our memories and experiences in our past that have sent us spiraling.”

The installation involves the viewer in multiple ways. Size matters here, as some of Ehrlich’s fabric hangings exceed the viewer’s height. Darkness and lightness matter, and they alternate in these thickly textured webs. As curator Lewis observes, Ehrlich should be regarded as “an inner-world scuba diver,” one who involves us deeply in her explorations.

At almost the opposite end of the metro area and type of venue, Hannah Helton’s In the Ruins, at Empire Arts Gallery through March 25, uses textiles in small mixed media collages to draw the viewer into an examination of “apocalyptic anxiety” that explores “religion vs. spirituality, tameness vs. wildness, and order vs. chaos.”

Many of the works fulfill such ambitious titles as Love Incarnate and Something New Under the Sun. In their intimacy, the different overlaid materials create their own metaphoric entanglements to accompany the literal ones of Helton’s textured surfaces.

::

Dr. Jerry Cullum’s reviews and essays have appeared in Art Papers magazine, Raw Vision, Art in America, ARTnews, International Journal of African-American Art and many other popular and scholarly journals. In 2020 he was awarded the Rabkin Prize for his outstanding contribution to arts journalism.

[ad_2]

Source link