[ad_1]

Imagine you are the boss of a bank financed only by debt and next to no equity. Much of this debt serves as the money used by the public to pay their bills, while the bank’s assets are both illiquid and risky. This, you might assert, is a fairy story: nobody would lend to such a business. But suppose lenders were sure these debts were guaranteed by taxpayers. It would then become a money-making machine: all upside; no downside.

Again, you might imagine that no governments would make such a commitment. Formally, of course, their guarantees are limited to smaller deposits. But there can still be implicit guarantees, because governments do not want banks to collapse in a panic.

Again, one would expect governments to ensure that banks do not get such guarantees for nothing: they would insist on substantial risk-bearing equity and large holdings of safe liquid assets.

Before the global financial crisis, there were indeed some such requirements. But they were ineffective. For many significant institutions the ratio of equity to total assets was only some 2 per cent.

How did this happen? Banks were allowed to mark their own homework by “risk-weighting” their assets. In this way the “risk-weighted capital ratio” could be magically increased. These weights were drawn from experience. In 2006, this suggested that risks had never been smaller. Banks were deemed exceptionally safe just as they became exceptionally unsafe. That is what happens in credit gluts.

Thereupon a series of “surprises”, notably the falling house prices, destabilised the system. The solvency and liquidity risks were indeed socialised. The belief that states guaranteed the banking system proved correct.

Allowing much of the banking sector to operate with near zero equity and an upside-only contract for bankers was mad. It happened partly because of the belief that “it is different this time”. Also, almost everybody loves a credit boom. But, in the case of the UK, there was something else: the belief that banking is a profit centre for the economy. And so, it was concluded, the country’s finance must be kept “competitive” by “light-touch” regulation.

We would never let finance go rogue like that again, one might hope. But it is now some 15 years since the crisis and, in the UK in particular, the government is desperate for growth and investment.

I am hardly surprised then that the new city minister, Andrew Griffith, has stressed a new obligation on regulators to “facilitate growth and competitiveness”. The latter idea also permeates the Financial Services and Markets bill now going through parliament. After all, “opportunities of Brexit” are bound to include more permissive regulation.

So far, the steps are modest. This is also true of recently suggested modifications to the “ringfencing” regime introduced after the 2011 report of the Independent Commission on Banking (of which I was a member). But a journey of a thousand miles starts with a single step.

Ringfencing forced banks to create a separately capitalised retail subsidiary. The aims are to isolate banking activities, where continuous provision of service is vital to the economy and customers, facilitate resolution of failing banks, and so eliminate implicit guarantees to investment banking activities, which UK regulators can hardly monitor and are of no evident value to the UK public.

This logic still applies. Remember too that, pre-crisis, the balance sheets of UK banks were five times GDP, much of this consisting of global activities. Banks were too big to fail, but, for the UK, almost too big to save. Ringfencing helps limit these risks. Encouragingly, Bank of England research even finds a “ringfence bonus”: it “is perceived by third parties as insulating the ringfenced bank subsidiary from risk”. Yet “there is no significant impact on the perceived riskiness of the non-ringfenced bank”.

Ringfencing was partly justified by what we considered excessively low requirements for equity. Is this concern now outmoded? Absolutely not.

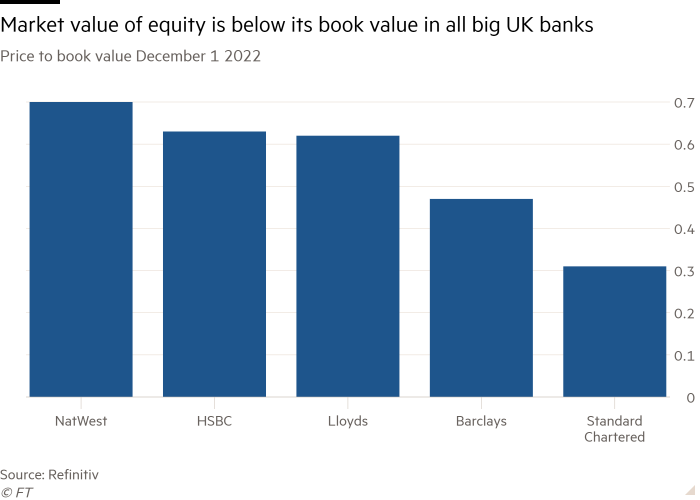

Yes, there is more equity in banks now, but not that much more. The ratio of equity to assets in UK banks in the first quarter of this year was only 5.3 per cent. That is really a rather small cushion. Worse, these ratios reflect the values in banking books. Markets value bank assets at below their book value in the UK (and everywhere else, except North America). This suggests that investors doubt the quality of the assets and so of bank equity. This is a disturbing signal.

We must not relax the ringfence, not least because UK banks remain undercapitalised. More broadly, the idea of promoting competitiveness by relaxing regulation is perilous. The risks will emerge slowly: Sunak and the rest of his government will be long gone. But the mantra of “competitiveness” will start the journey down a dangerously slippery slope. We must be careful: banks built on upside-only bets for their decision makers are sure to crash.

[ad_2]

Source link