China’s economic outlook was already challenging at the beginning of the year, as the effects of President Xi Jinping’s crackdown on property and other high-growth industries rippled through the world’s second-largest economy.

But the view has deteriorated ahead of the National Bureau of Statistics’ April 18 release of its estimates for first-quarter gross domestic product growth. Meanwhile, Xi’s administration is grappling with a Covid-19 nightmare that has gripped some of the country’s largest cities over the past month.

Monday’s statistical release will capture only a small sample of the upheaval stemming from the lockdown in Shanghai, China’s most populous city and its most important financial and manufacturing centre, which did not become a full-blown crisis until the end of March.

Previously, large-scale disruptions were concentrated in the northern city of Xi’an, which had a surge in cases in January, and more recently in Jilin province, an important agricultural producer and automotive centre.

The knock-on effects of the Shanghai lockdown have been far greater than those in either Xi’an or Jilin, so no matter how badly the first quarter numbers come in, they will probably only get worse in coming months. Here are five things to look out for with Monday’s release.

How realistic is the government’s official annual growth target of 5.5 per cent?

When Premier Li Keqiang announced the 5.5 per cent target at the opening of China’s annual parliamentary session on March 5, it struck most analysts as aggressive, especially in light of his repeated pledges not to resort to “flood-like stimulus” while also “keeping the [national] macro leverage ratio generally stable”.

China’s economic output expanded 4 per cent year on year over the last three months of 2021, down from 4.9 per cent in the previous quarter.

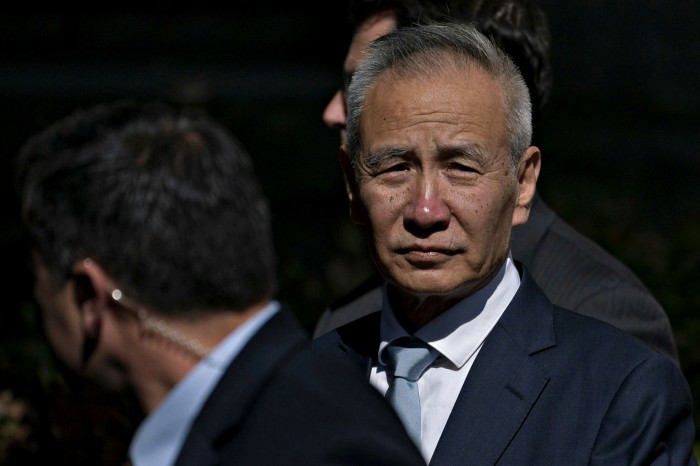

Vice-premier Liu He, Xi’s most trusted financial and economic adviser, has staked his reputation on maintaining discipline and not letting debt levels blow out as they did during an investment binge unleashed by Beijing in the wake of the 2008-09 global financial crisis.

But both Li and Liu are now clearly worried about the health of the economy. Liu made a rare intervention in March to boost confidence in the economy and stock markets, which had been rattled by a combination of Covid lockdowns and the inflationary effects of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Will zero-Covid politics trump concerns about the economy?

The success of China’s zero-Covid approach to managing the pandemic in 2020 and 2021 has become a central part of Xi’s political legacy, and a justification for his pursuit of a third term as head of the party, state and military.

Xi has repeatedly said that local officials should achieve zero-Covid while ensuring minimal disruption to the economy and people’s lives. Shanghai initially tried to achieve this by locking down one half of its population for five days, followed by five days for the other half.

But the compromise approach could not contend with the infectiousness of the Omicron variant. As Shanghai’s daily case count raced past 20,000, a de facto citywide lockdown followed with no clear exit strategy.

Other cities with negligible daily case counts are now resorting to pre-emptive restrictions and all-out lockdowns. Ernan Cui at Gavekal Dragonomics, a Beijing consultancy, estimated that almost three-quarters of China’s 100 largest cities, accounting for more than half of national GDP, are enforcing Covid-related restrictions.

Barring a clear signal from Xi that zero-Covid zealousness has gone too far, the economy will continue to bear the brunt of its consequences. On Wednesday, Xi reiterated that there would be no significant relaxation of the policy.

How big a hit is consumption taking?

Lockdowns make it difficult for people to go out and buy consumer goods, cars and even flats, with predictable consequences for the economy.

Car sales were suffering before Shanghai announced its partial lockdown on March 26, and ended the month almost 12 per cent down year on year. Prospects for a rebound in April are not bright given the restrictions in Shanghai and Jilin, both big automotive centres.

Property sales were also stagnating before China’s March lockdowns. New home prices declined slightly in February compared with January, despite measures taken by local governments across the country to boost sales, as well as the first cut in China’s benchmark mortgage lending rate since 2020.

Will the government resort to covert stimulus measures to boost the economy?

Total social financing, a broad measure of credit in the Chinese economy, soared 38 per cent year on year in March to Rmb4.65tn ($730bn), compared with previous expectations of an 8 per cent rise.

It was a repeat of March 2020, when shortly after the pandemic erupted in central China, total social financing reached Rmb5.18tn.

Chinese banks also extended loans totalling Rmb3.1tn in March, about 2.5 times the February figure.

Is foreign investor patience approaching breaking point?

This week, Jörg Wuttke, head of the European Chamber of Commerce in China, warned that the recurring outbreaks and authorities’ strict responses were “eroding foreign investors’ confidence in the Chinese market”.

According to recent surveys of German investors in China, half of respondents reported that their supply chains had been “completely disrupted or severely impacted”, while a third said their manufacturing operations had been similarly hit.

“The Omicron variant,” Wuttke said, “is posing new challenges that seemingly cannot be overcome by the old toolbox of mass testing and isolation.”