[ad_1]

John Harvey Kellogg and his younger brother William invented one of the first breakfast cereals in the 1890s as a health food to aid digestion, but John was furious when William created a version with added sugar.

More than a century later, William’s company, now known as Kellogg, is still at the centre of a conflict between flavour and health. As governments and investors press food companies including Kellogg to make their products more nutritious, the US group has in turn taken legal action against the UK government over an attempt to restrict marketing of some of its cereals because of their sugar content.

The lawsuit is the latest sign of the tensions as governments and investors seek to address a global obesity problem that has been exacerbated by the Covid-19 crisis, even as inflation squeezes consumers’ wallets and intensifies foodmakers’ battle for market share.

“For shareholders like LGIM, nutrition and in particular obesity have become systemic risks for companies we hold across multiple sectors,” said Maria Larsson Ortino, global environmental, social and governance (ESG) manager at Legal and General Investment Management, one of Europe’s largest asset managers.

“We are actively engaging with those companies that have high revenue exposure to unhealthy products, as we believe they are likely to face the dual headwinds of increasing regulation and limitations on marketing of unhealthy foods.”

Nutrition has climbed the agenda as investors interpret ESG principles more broadly, moving beyond climate to social problems, said Bruno Monteyne, an analyst at Bernstein.

Obesity has almost tripled since 1975 and packaged and “ultra-processed” foods have received a large slice of the blame. US-based public health group Vital Strategies last year called for tobacco-style warnings on the health risks of highly processed foods. Chile has already introduced black warning labels shaped like stop signs on packaged foods and drinks high in sugar, salt or saturated fat (HFSS).

Investor groups have campaigned on nutrition for several years: the US-based Interfaith Centre on Corporate Responsibility, bringing together investors with more than $4tn in assets, has been engaging with food and drinks makers on the issue since 2014.

But Covid-19, which tends to be more severe in patients with obesity and related conditions such as diabetes, upped the ante.

In the past year, multinationals including PepsiCo, Coca-Cola, Kraft Heinz, Kellogg and Nestlé have been hit with shareholder resolutions on nutrition. Unilever this year pledged to overhaul its nutrition disclosures and set new goals after being targeted by the UK investor group ShareAction.

The concern is not just that food and beverage makers contribute to social harms like obesity but that they may find themselves on the back foot as governments take a more active approach.

Over the past decade, dozens of countries, including Mexico, South Africa, the UK and parts of the US, introduced taxes on high-sugar soft drinks, a move that cut sugar consumption through those drinks and pushed manufacturers to reformulate their products.

The UK had planned fresh restrictions on the marketing of HFSS foods from October, banning buy-one-get-one-free deals, free soft drink refills and the advertising of junk food on television and online.

Global food groups have responded with new versions of their products. Mars, for example, last month launched lower-sugar, higher-fibre versions of its Snickers, Mars, Galaxy and Bounty bars in the UK.

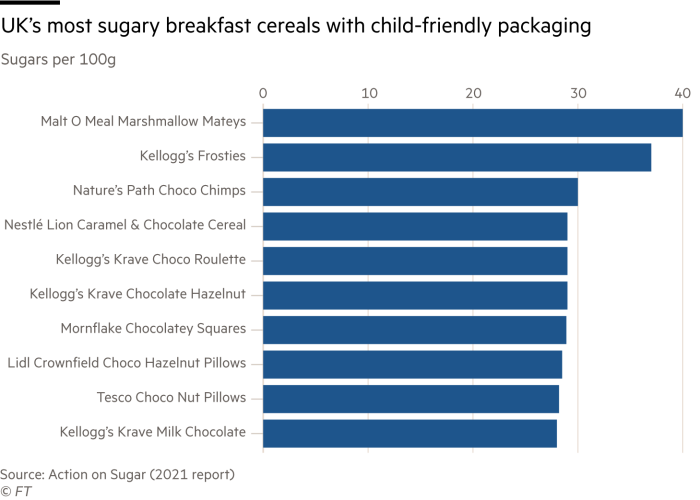

But Kellogg, maker of Coco Pops, Frosties and Froot Loops, launched a judicial review, arguing that the HFSS criteria did not take into account the milk with which its products are usually consumed. A judgment has not yet been issued.

Kellogg said: “We’ve turned to the courts to seek an improvement to the formula, so that it reflects how people eat our food in real life. Of course, we will continue our efforts to engage with the government as we have always done.”

Kellogg’s action raised eyebrows among investors. Marie Payne, responsible investment officer at Dutch asset manager Actiam, said: “I was actually quite disappointed. I found it quite incredible . . . The fact that cereal is taken with milk does not make the underlying product healthy.”

Yet food groups won a victory of sorts last month when the UK government postponed most of the rules — apart from new regulations on the locations of unhealthy foods in shops — for a year, citing pressures on the cost of living.

The delay has raised questions over whether the nutritional credentials of branded foods will remain high on the agenda at a time when global food poverty is skyrocketing.

“Wellness has a resurgence from time to time but then it dies away again because of something like inflation,” said Steve Wreford, a portfolio manager at Lazard Asset Management. “Large companies have been around for a lot longer than a typical government and they have learned to move slowly in these areas [such as nutrition] because of legislative volatility.”

Sébastien Thévoux-Chabuel, a fund manager at French asset manager Comgest, said: “There’s a real risk that nutrition may be a bit of a luxury at a time of commodity shortages, rising inflation and a cost of living crisis . . . More people may end up turning to unhealthier products because they are cheap and they have no other choice.”

11,000

Tonnes of sugar Kellogg says it has removed from its products since 2011

When it comes to demand, some investors see health and wellness as a trend squarely aimed at wealthier consumers. Organic and “natural” businesses tend to be higher margin.

“You can make premium products and invest in broader wellness trends or you can be mass market,” said Wreford. “A handful of companies, like Costco, are able to bridge both.”

But governments want to improve nutrition across the board, and Monteyne argued that while economic conditions might delay regulatory measures, they would not halt the trend.

“Telling people what to eat is inherently difficult politically and inflation will make it harder, which is very unfortunate, in my view,” he said.

“You could have a bit of timing delay [to legislation] but the underlying trends are going to be there . . . Ultimately it will come because the costs to the healthcare system [from obesity] will be greater than the political costs.”

Obesity and related problems cost the UK’s National Health Service £6.1bn in 2014-15, a sum expected to rise to £9.7bn a year by 2050.

Two of the UK’s “big four” supermarkets, J Sainsbury and Tesco, said they would push ahead with removing buy-one-get-one-free deals on unhealthy foods this year despite the government’s delay.

For food brands, an important risk is that removing salt, sugar or fat will make some products less tasty and reduce a brand’s competitive advantage, where regulation does not create a level playing field.

Reduced-sugar Nestlé and Cadbury chocolates launched in the past five years failed to attract consumers, but Premier Foods says its lower-sugar, higher-fibre versions of Mr Kipling cakes and pies are selling well. Kellogg says it has removed 11,000 tonnes of sugar from its products since 2011.

The cereal maker said that four of its five best-selling brands in the UK do not count as HFSS, adding: “Across the globe we continue to evolve our portfolio . . . including options with less sugar, sodium and saturated fat as well as innovating foods with more fibre, protein and micronutrients.”

For the moment, investors are still pushing for basic disclosures on health. “Part of the challenge for investors is knowing how healthy are the underlying portfolios of the consumer goods groups, and measurement here is opaque,” said Jessica Ground, global head of ESG at Capital Group, the $2.7tn asset manager that is a top-10 shareholder in Kellogg and Nestlé.

She acknowledged that attempts to make products healthier would add to spiralling production costs.

“We are trying to understand what they are doing to reform existing products and introduce new products in the face of an increasing demand for healthier food,” she said. “All of this costs money, takes time and could put pressure on margins.”

[ad_2]

Source link