All Barney ever wanted was to love us. From the moment former Dallas schoolteacher Sheryl Leach breathed him into life, the purple Tyrannosaurus rex was a reptile of exceptional warmth. His bulbous, spongy body was made for hugs. His dinosaur maw had been capped in a blindingly white smile that would have made Tony Robbins jealous. Barney preached—gently, secularly—on the value of friendship. “I love you / You love me,” Barney sang. “Won’t you say you love me too?”

But we didn’t love Barney. Maybe it was his desperate need for validation. Maybe it was his presumption. (We love you? Really?) Whatever the reason, what Barney got in return was our hate.

When Barney & Friends debuted on PBS on April 6, 1992, it was an immediate hit, in a way that the modest regional success of the earliest, straight-to-video Barney specials—backed by Leach’s father-in-law and filmed in the Dallas suburb of Allen from 1988 to 1991—certainly never predicted. Barney embarked on a tour of shopping malls that drew thousands of toddler acolytes. By that Christmas, stores couldn’t keep Barney dolls in stock. In January, he waved from Bill Clinton’s inaugural parade. Barney’s sudden ubiquity seemed inexplicable, especially to parents, who despised his dopey demeanor, his reflexive giggling, and his inane exclamations of “Super-dee-duper!” The critics didn’t get it either. They blasted Barney for being insipid, irritating, and even dangerous. They decried the saccharine world Barney lorded over, where every problem could be waved away with a song—songs that proved so cloying, by the way, that interrogators at Guantanamo used them to torture Iraqi prisoners.

Mostly, though, adults hated Barney because their kids couldn’t get enough of him. To his creators, that was all that mattered.

“We really don’t care whether the adults are going to be entertained,” Leach told the Chicago Tribune in 1992. Jerry Franklin, who had helped develop Barney’s show for PBS, was even more blunt. When adults say they dislike Barney, Franklin told the Hartford Courant, “in a way, we take that as a compliment.”

By the end of the nineties, Franklin must have been feeling really flattered indeed. Adults—and just about everyone over the age of five—had turned not liking Barney into a cultural movement. “Anti-Barney humor” was so widespread, it was practically its own form of comedy. There were the usual punch lines from the drive-time DJs and late-night hosts, and there was the immortalizing spoof on The Simpsons. But mostly, “anti-Barney humor” involved watching some copyright-skirting Barney stand-in get the stuffing kicked out of him.

Animaniacs dropped anvils on “Baloney the Dinosaur.” On ABC’s Dinosaurs, “real” dino dad Earl whaled on a hippo host named Georgie. Barney-alikes were screamed at by Robin Williams in Death to Smoochy and lampooned (and harpooned) in Mafia! In 1993, Charles Barkley took Barney on in a brutal game of one on one for Saturday Night Live; the crowd went wild at every elbow to Barney’s face. The tone of anti-Barney humor was hostile, even violent, in a way that had never been seen before—or since. Today’s parents might “hate” Caillou. But you won’t find hours of YouTube videos where he’s bludgeoned, blown up with dynamite, doused with gasoline and set on fire, or shot at point-blank range. It’s hard to imagine a bunch of childless college students paying good money to whack Paw Patrol dolls with hammers.

Such passionate, generation-transcending hatred for Barney was a product of its time, an era when the monoculture hadn’t yet fragmented into a million niches and we could all stand united behind our contempt for certain inescapable phenomena. Not coincidentally, Barney’s rise also converged with that of the internet. Barney was low-hanging fruit that everyone could make fun of—a favorite punching bag of Usenet newsgroups, which shared stories and crude games in which Barney was tortured or killed and made an early viral hit out of Tony Mason’s 1993 parody song “Barney’s on Fire.” They formed online clubs like the Anti-Barney League, the I Hate Barney Secret Society, and the Jihad to Destroy Barney, whose members swapped half-ironic manifestos about Barney’s plot to mold our children into pliant communists, and chuckled over dorky mathematical “proofs” that Barney was Satan. Those same internet back channels are also where rumors took hold that Barney was actually based on a 1930s serial killer, or that he was secretly played by a child-hating, cocaine-fueled monster.

Most of this was just good, antisocial fun. But the rancor occasionally spilled over into the real world, too, like with the North Carolina preacher who denounced Barney as a “New Age demon,” railing against “the Purple Messiah” in pamphlets and on the radio. Throughout the nineties, there were reports of Barney impersonators being assaulted at store openings and the like—in Massachusetts, Indiana, and even right here in Texas. Barney may not have been the Antichrist, exactly, but something about him awakened the devil in people.

As much as all the Barney hate seemed a little irrational—or at least disproportionate—Barney’s creators also made him pretty easy to dislike. Sheryl Leach liked to tell a sentimental story about how she dreamed up Barney while she was stuck on Dallas’s Central Expressway, brainstorming ways to entertain her rambunctious two-year-old son, Patrick. But Barney’s mythology usually elides the next part, in which Leach and her business partner, Kathy O’Rourke Parker, developed the show through market research and rigorous focus-group testing. Unlike Jim Henson or Shari Lewis, who sought to maintain a sense of magic and kinship with their characters, Leach could often be found talking about Barney in terms of cold business strategies and “success formulas” while her creation cavorted dutifully behind her. Leach was also markedly humorless about criticisms: When she spoke before the National Press Club in 1993, she didn’t just brag about projected revenues to a bunch of bored, disappointed toddlers (although she definitely did that). She took the opportunity to sternly lecture Barney bashers, suggesting that all their little jokes were inflicting real psychological damage on innocent children.

“The children” were also the inspiration cited for the numerous lawsuits filed over the years by Barney’s parent company, Allen-based Lyrick Studios (formerly the Lyons Group), which was purchased by HIT Entertainment in 2001. Lyrick aggressively went after just about anyone who used Barney in an unauthorized fashion, parody or not. This included many of the websites that had hosted those Barney spoofs, no matter how tiny. Barney’s corporate parent took its most saber-rattling action against seven hundred or so costume shops that were caught selling unofficial, adult-size Barney getups. None of this was about copyright or money, Lyrick insisted. They simply wanted to “protect the children,” the company’s then-CEO, Tim Clott, argued to Texas Monthly in protest of Barney’s 1999 Bum Steer award. Of course, that air of self-righteousness only added fuel to the fire—not that I’m suggesting anyone should set Barney on fire! (Please don’t sue me.)

There were certainly other reasons to feel put off by Barney, although many of them had even less to do with him. Yes, Barney’s Universal Studios attraction was built on the old Bates Motel set from Psycho IV. But surely that was just a creepy coincidence, not some symbolic endorsement of Barney’s evil. It’s also true that the man inside the Barney suit for the show’s first six seasons, David Joyner, later opened a “tantric massage” clinic where he, uh, serviced an exclusively female clientele by having unprotected sex with them, then gave a dizzyingly graphic interview about it to Vice. But that’s not Barney’s fault. Should Barney be similarly linked to the tragedy of Patrick Leach, Sheryl Leach’s son and original muse, who was sentenced in 2015 to fifteen years in prison for shooting his neighbor? Nearly every article about it led with a photo of the purple guy’s smiling face, but that’s not entirely fair either.

The truth is, when we are faced with something as popular and pious as Barney, perhaps it’s only natural to respond with cynicism—to look for darkness in the light and find something sinister about the supposed purity. When Barney & Friends quietly stopped making new episodes in 2009, the lack of official announcement created another void that the internet again rushed to fill with suspicion and pessimism. Surely the “dark truth” behind the cancellation, some theorized, lay in the show’s many controversial lawsuits, or the shadow cast by Joyner’s unsavory personal life, or the cumulative years of “public scorn.” But really, those are adult hang-ups. As Barney’s creators had always argued, none of that stuff matters to preschoolers. The end of Barney surely had less to do with negativity than with competition from Netflix, as well as the inexorable passage of time.

Today, of course, Barney’s kids are the adults. Most of them long ago grew out of their Barney phase; some of them may have even moved straight into hating him. But now a lot of them have kids of their own. And thirty years after Barney & Friends premiered, any lingering Barney hate is about to be mitigated by another factor: nostalgia. Peacock is readying a three-part Barney documentary that’s set to air later this year. Get Out star Daniel Kaluuya, an unabashed Barney fan, says he’s working on a new live-action Barney movie, arguing that the character has been “left misunderstood” and that we need Barney’s love and optimism today more than ever. While a promised TV reboot has yet to materialize, it seems only a matter of time before Barney is fully revived—and, quite possibly, redeemed.

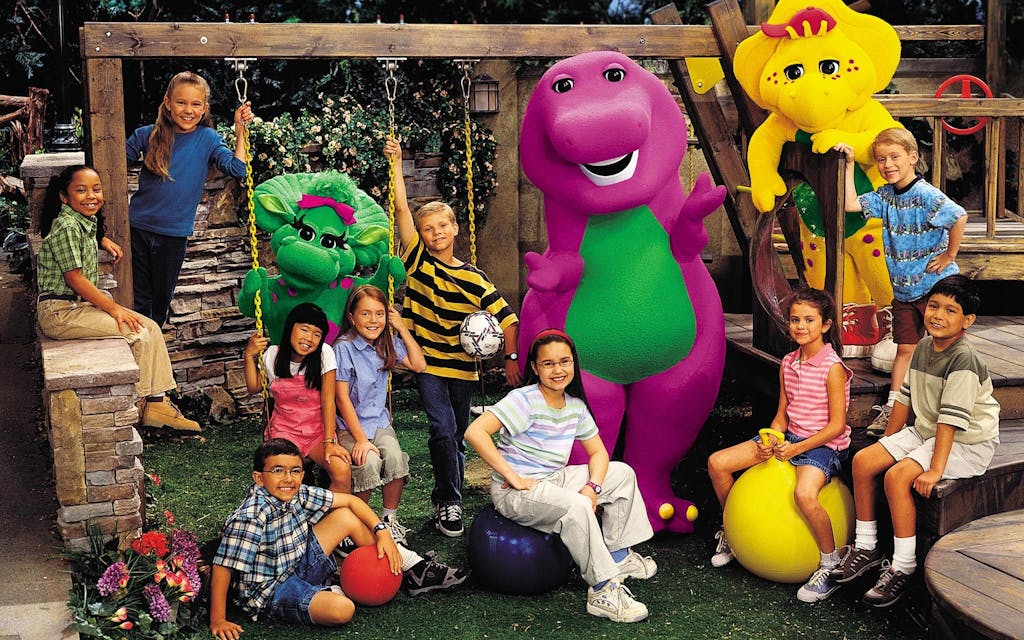

After all, Barney’s legacy is now bigger than any one dinosaur. We also have Barney to thank for the careers of Selena Gomez and Demi Lovato, who both spent two seasons as part of his crew. Maybe Barney & Friends can’t compete with the 1990s Mickey Mouse Club that produced Christina Aguilera, Ryan Gosling, Kerri Russell, Britney Spears, and Justin Timberlake. But it proved to be its own powerful incubator for future Texas stars, with a roster that also includes Madison Pettis, Debby Ryan, and Danielle Vega. For years, Barney was the best résumé-builder in town for aspiring child actors, giving them the rare boon of a regular gig, as well as an unusually nurturing space where they could hone their skills. Perhaps it’s worth noting that Gomez and Lovato have become not just two of our biggest pop stars, but also two of our most visible advocates for mental health—roles that seem like a natural outgrowth of Barney’s touchy-feely community.

Barney & Friends had a similarly positive impact on Dallas’s film and television scene, generating millions in local production dollars as the show shot first in Allen, then at Irving’s the Studios at Las Colinas, then finally at HIT Entertainment’s own studios in Carrollton. Local filmmakers may have groused at the time that Barney and Walker, Texas Ranger dominated the Metroplex—that Austin got all the cool independent stuff, while the Barney grind instilled a corrosive “studio mentality” in Dallas creatives, as late filmmaker Andy Anderson lamented to the Dallas Observer. But at the same time, Barney sure kept a lot of people employed. And while Barney’s old studios in Carrollton and Irving are long gone—the former is now a showroom for massage chairs; the latter currently hosts the make-believe world of Glenn Beck—in their heyday, both served as cornerstones of Dallas’s perennial “Third Coast” aspirations, with untold numbers of film and TV workers learning their crafts at Barney’s giant feet.

In fact, now that we’ve had a few decades or so to get over how annoying he is, maybe we can take some selfish regional pride in Barney. Here was a character so universally popular that he briefly supplanted Mickey Mouse and Big Bird in children’s fickle hearts, while also earning widespread abuse across the entire spectrum of our culture. Phenomena like that don’t come along very often, and they likely won’t again. And it’s all the more remarkable that this happened here, right in our own magical backyard. With apologies to Wes Anderson, Richard Linklater, and Robert Rodriguez, Barney remains Texas’s biggest homegrown success story.

Are we finally ready to say we love Barney too? Okay, maybe not. But perhaps the mellowing years have allowed for a bit more nuance than a simple binary of “love” or “hate.” As Barney himself could tell us, people have a lot of different feelings—sometimes too complex to even sing about. Thankfully.