[ad_1]

Editor’s note: To mark the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, we’re re-sharing this conversation with a remarkable woman who is among the world’s more than 500 million indigenous peoples.

Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim grew up in an Mbororo indigenous community in south-central Chad. Ibrahim — a former Conservation International (CI) indigenous leaders conservation fellow and one of Vogue’s so-called “climate warriors” — recently shared what motivates her to keep leading the charge in promoting the rights of indigenous peoples.

Question: How did you make the leap from your community in Chad to the global stage?

Answer: I never stop thanking my mom. When I was young, my mom had a friend who was sick; one time the woman drank medicine and got sicker. When my mom took her to the hospital, the doctor said that she could have died; the medicine wasn’t

for drinking, but because she couldn’t read, she didn’t know. My mom realized this since she was also illiterate, this could have happened to her, too. She decided then that this would never happen to her kids. So she sent all of us to

school: my three brothers, my sister and myself. The people in her community thought she was crazy, especially educating girls.

Every time we had a school vacation, we returned from the capital of N’Djamena to my mom’s community. She didn’t want us losing our culture, but she also didn’t want us to miss out on the value of Western education. For many years,

she worked incredibly hard — never sleeping, selling cows to pay all our school expenses.

As I got older, I became more aware that across the world, indigenous communities are among the most marginalized populations. In my efforts to create a community organization that would protect indigenous and human rights and encourage environmental

protection, I eventually was invited to attend a meeting about indigenous women in Cameroon in 2000; that was the first time I got involved internationally.

Q: You grew up near Lake Chad. What is special about this area, and what is happening there now?

A: As semi-nomadic herders, the Mbororo people traditionally migrate close to Lake Chad during the dry season, when there are few other sources of water for their cattle. The lake also provides essential drinking water, fish and seasonal farmlands

for millions of people.

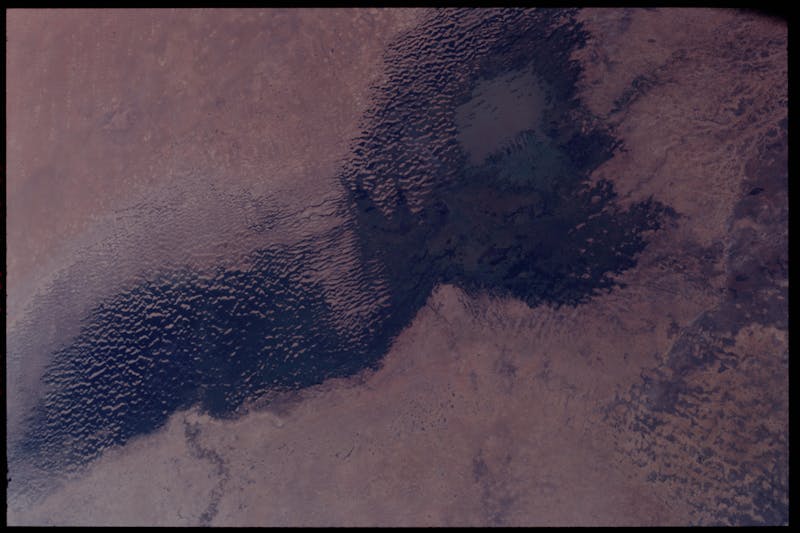

The problem is, over the past 50 years, Lake Chad has shrunk by more than 90% — from 25,000 square kilometers [9,650 square miles] to less

than 2,000 square kilometers [770 square miles]. There are no large-scale activities around the lake that would account for this loss — no dams, industry or large irrigation systems for agriculture — so it seems clear that the cause is

climate change.

Satellite image of Lake Chad taken in 2001. Over the past 50 years, the lake has shrunk by more than 90%. (NASA Photo ID: ISS001-355-4, http://eol.jsc.nasa.gov; image courtesy of the Earth Science and Remote Sensing Unit, NASA Johnson Space Center)

This has always been a hot place, but we’ve never experienced this level of heat before. At the start of this year’s dry season, it was 46 degrees Celsius [115 degrees Fahrenheit], which is a record. At this rate, what will it be during the

season’s peak?

Normally the lake is divided between Chad, Cameroon, Niger and Nigeria, but due to its size reduction, most of the water is currently within Chad’s borders. Many fishers from the other countries are now coming into Chad to fish. Farmers in the lake’s

floodplain are also starting to expand their farms because the small ones aren’t yielding enough. On top of this, pastoralists like the Mbororo have to come to the lake earlier in the year because of the lengthening dry season — and now

when they get there, all of the land is occupied.

All of these issues are combining to escalate conflict in the region. Access to water is becoming a huge problem, with people fighting and killing each other. (Learn more about the challenges facing Ibrahim’s community in the video below.)

Q: You were one of CI’s first indigenous leaders conservation fellows in 2010. How did this program help advance your work?

A: The fellowship didn’t dictate what I should do, which was unusual in my experience, and which I appreciated. I wanted to focus on climate change because I saw how it was affecting my community, but at the time I couldn’t follow the

global climate negotiations, because they were all in English. So my first goal was to improve my English; I spent a month in Nairobi doing so.

Next, I wanted to study how indigenous traditional knowledge could help my community adapt to climate change. I did research on this for one year, and it’s the basis of all the work I’m doing now. I found that there is a lot of knowledge within

my community. Almost six years later, I’m still working with other organizations to figure out the best way to document all of it.

Q: What have you learned since?

A: One way we are adapting is through weather-casting: using ecological observations to help us move from place to place. By observing environmental changes — from the liquid inside certain types of fruit, to the flowers, to the position

of the stars — we can predict the strength of the next rainy season and can be more prepared.

For example, if certain birds make their nests in branches near the water, you know that the next year will not have heavy rains. If they build the nests in the tops of the trees, then you know that the whole area will be inundated.

Q: You’re a co-chair of the International Indigenous Peoples’ Forum on Climate Change, which represents indigenous groups worldwide in U.N. climate negotiations. What were your goals for the Paris meeting last December, and were you satisfied with the outcome?

A: The forum is split into seven geographic regions, all of which first organized local consultations on climate change issues before the Paris meeting. In Chad I organized a community meeting to discuss what people were expecting from the Chadian

government in Paris; we then shared our suggestions with the government ministers. We were happy that they incorporated language we suggested about human rights, biodiversity and gender issues into the country’s INDC [the national climate change

action plan submitted by each country before the Paris meeting].

The indigenous forum then consolidated all of these local recommendations into a global position on indigenous people’s rights, which advocated for the value of traditional knowledge, inclusion of indigenous peoples in decision-making and the need

for direct access to climate funding. We also knew we wanted the recognition of indigenous peoples and rights inside Article 2, which is part of the legally binding text.

In the final Paris Agreement, indigenous peoples got five references — but indigenous peoples’ rights were not mentioned in the legally binding section. So the outcome is not too bad, but it’s not the level of commitment we wanted, either.

Mbororo people are semi-nomadic herders who rely on Lake Chad to provide water for their cattle during the dry season. As temperatures increase and the lake continues to shrink, the Mbororo are coming into more frequent conflict with others in the

region as herders, fishers and farmers fight to access the dwindling resource. (© OCHA / Mayanne Munan)

Q: How has being a woman shaped your role as an activist?

A: In most African communities, men are the head of the family and community, and women do not have a role to play in decision-making. I have tried to change this in the villages where I work. It’s been challenging, but I’m slowly seeing

changes happen. Now I can sit and talk with all the chiefs; I give them recommendations, and they execute them. I am always fighting for the rights of the woman.

We also need to fight this at the international level. Because of their relationship to the environment, women will be disproportionately affected by climate change.

But only in 2014 did gender and climate change become a major topic within the climate negotiations — and this convention has existed since 1992. When you look at the people involved in international climate change discussions, most of them

are men. If we want change, we have to start there.

In addition to her role with the International Indigenous Peoples’ Forum on Climate Change, Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim is a coordinator of the Indigenous Women and Peoples Association of Chad, as well as a member of the Executive Committee of the Indigenous Peoples of Africa Coordinating Committee. Molly Bergen is the senior managing editor of Human Nature.

Want to read more stories like this? Sign up for email updates. Donate to Conservation International.

Cover image: Through groups such as the International Indigenous Peoples’ Forum on Climate Change, Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim helps to represent the world’s many indigenous peoples in global climate change negotiations. (© Conservation International)

Further reading

[ad_2]

Source link