Sometime in the past decade or so, the coining of new terms to help us understand what work is and how workers should relate to it reached unprecedented velocity. We were introduced to co-working and hybrid working, encouraged to lean in then out, to boss up and to werk. The utility of these neologisms in the longer term is doubtful. Not so for the work in this photography package, which grapples with the big question of the meaning of work at the same time as it documents the increasingly fragile security of many workers around the world.

MAKING

Ilyes Griyeb

Morocco, 2014-19

We are all descendants of farmers. If we go back through past generations, we all share the same fundamental history. I do not have to look too far back. The images in my series “Morocco” (2014-19) are of workers on my father’s land in the Meknes region in the north of the country. They all come from the countryside where my parents grew up, and most of them are kind of family or very close neighbours.

I believe agriculture is our past but mostly our future. If we still want to have an Earth to live on in this century, we will have to come back to a more human scale and a more respectful connection with our planet and each other. —IG

“Morocco” was published as a photobook in November 2020; ilyesgriyeb.ma/product/morocco/

Wang Bing

15 Hours, 2017

The town of Zhili accounts for 80 per cent of China’s output of children’s clothes. Part of the city of Huzhou in the province of Zhejiang, it is home to around 18,000 small factories for children’s clothing, staffed throughout the year by more than 200,000 migrant workers. In the 1980s, Zhejiang saw the emergence of a private capital-based garment industry open to any and all operators prepared to invest in flexible business models based on mutual credit or leasing. The film, 15 Hours, was shot in August 2016 and documents one day in the lives of the workers of 68 Xisheng Road in Zhili.

Maurice Broomfield

Industrial Sublime

Maurice Broomfield (1916-2010) made some of the most spectacular photographs of industry in the 20th century. His work spans the rise of postwar industrial Britain in the 1950s to its slow decline into the 1980s. From shipyards to paper mills, textile production to car manufacturing, he emphasised the dramatic, sublime and sometimes surreal qualities of factory work. Broomfield was born to a working-class family living in a small village near Derby, in the East Midlands. His parents and grandparents were from a farming background, but his father worked in a nearby munitions factory during the first world war, and later as a lace designer, producing detailed pen and ink drawings. As Broomfield wrote: “The impressions of my father making intricate and variegated conventionalised patterns in his peaceful studio, later to be fed into noisy, clattering machines to produce lace, had a considerable influence in my photography.”

“Industrial Sublime” is at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London until February 5

Carmen Winant

Pictures of Women Working, 2016

“Pictures of Women Working” (2016) was assembled over several years under a straightforward rubric: pictures of women working. This simple prompt unfolded in myriad directions: women in care work, women in sex work, women exercising, studying, beautifying, performing and so on. I wanted to think as expansively as possible, and not differentiate. The collected images are adhered to newspaper broadsheets that, though partially covered, also hold stories about the nature of gendered labour. Together they are meant to create a non-linear, semi-explosive constellation. One that demonstrates just how many kinds of work women are called to do, often at once. —CW

CARING

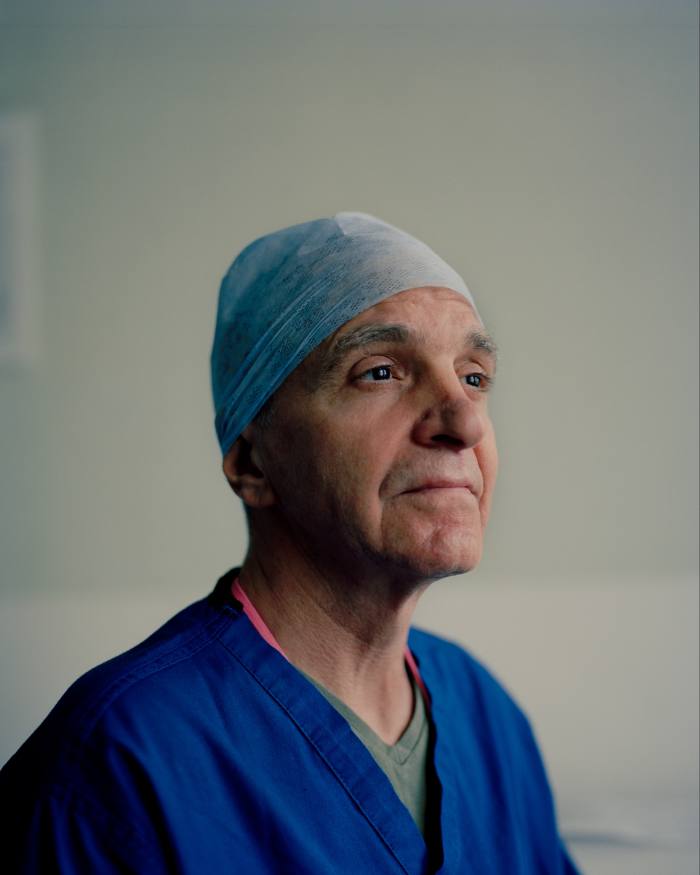

Lewis Khan

Theatre, 2015-19

Lewis Khan took these photographs as the culmination of an artist residency at two NHS hospitals, capturing the intimate realities of daily life there. With prolonged and unprecedented access, his series “Theatre” documents everything from high-level clinical procedures and the people who perform them to the hospitals’ cleaners and porters, staff rooms and bed bays. Seen through his eyes, it is often the small details that tell the story.

When Khan began the residency, he saw his work in part as standing “against the privatisation of the NHS”. As time went on, however, he began to view the series of photographs as a “much more universal study of human strength and fragility”.

“Theatre” was published as a limited edition photobook by The Lost Light Recordings in May 2020

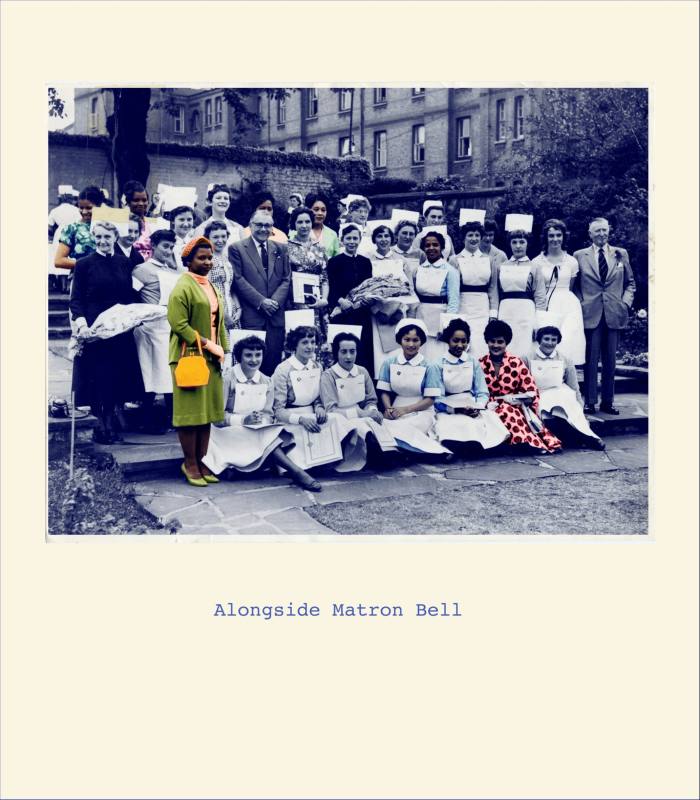

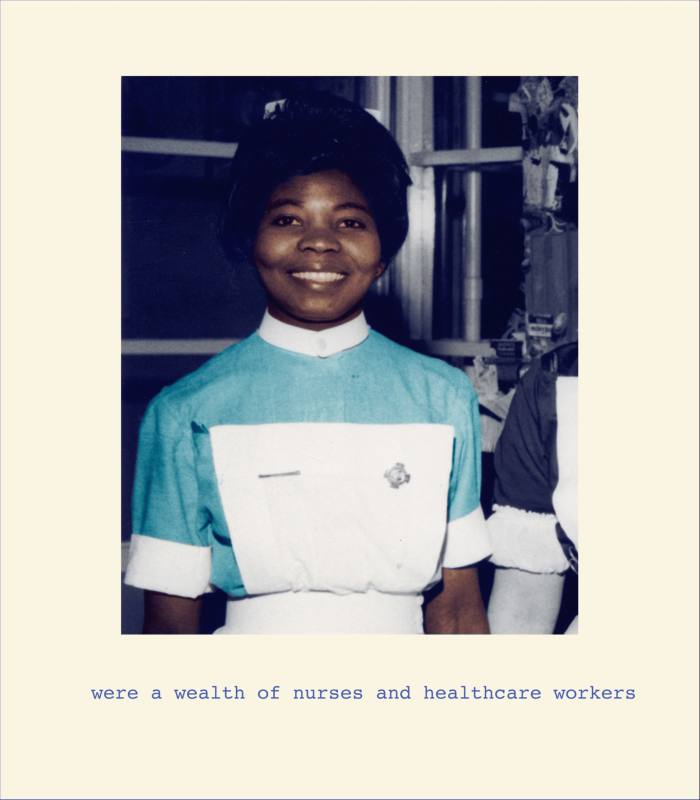

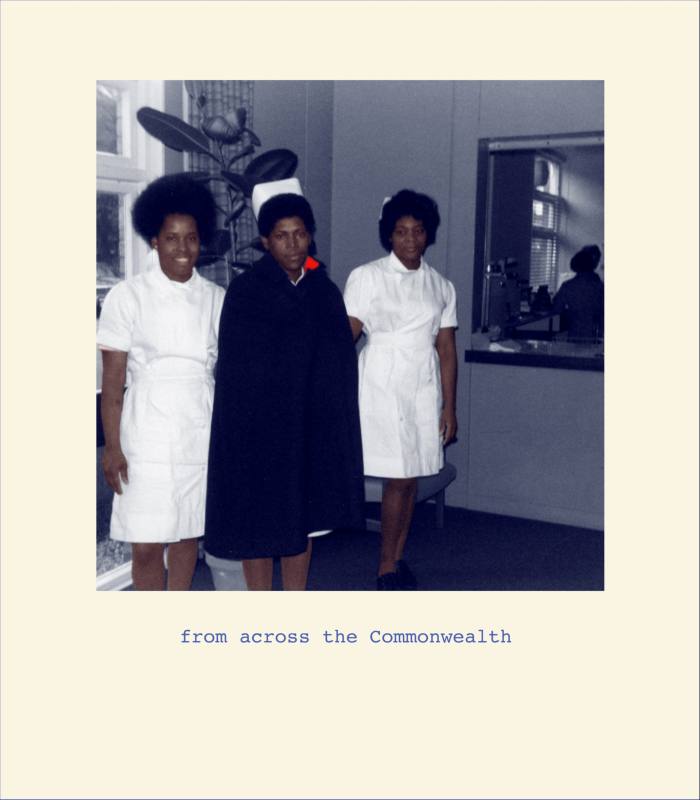

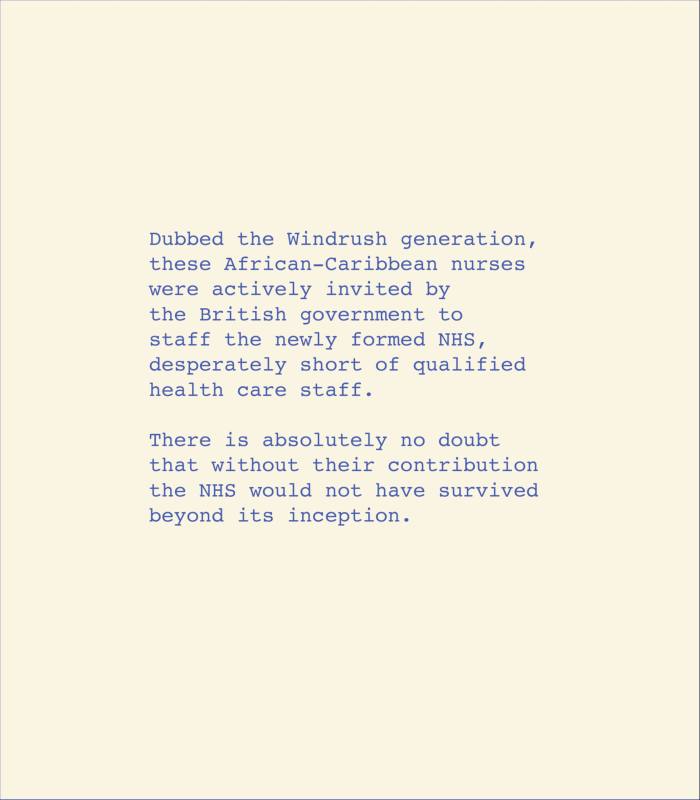

Joy Gregory

Alongside Matron Bell, 2020

In 2008, I was commissioned by Lewisham Hospital in south London to make a work celebrating 60 years of the NHS. After almost a year of intensive research, I chose to focus on Marjorie Bell MBE, who was appointed in 1948 as the first matron at the hospital under the NHS.

In 2020, I went back into the archives to make the project “Alongside Matron Bell”. I wanted to highlight the many nurses and healthcare workers at the hospital who, as the NHS was being established, were recruited from across the Commonwealth to build a dream for the “mother” country, as part of the Windrush Generation. In the hospital’s archives there are many photographs of these workers but their names are not recorded. —JG

Cole Barash

Smokejumpers, 2017

These photographs document the work of US Forest Service firefighters, who in some circumstances use parachutes to reach wildfires in remote areas of the country. Smokejumpers, as they’re known, must complete intense physical and mental training. They often stay in situ for 48 hours, miles away from help and without receiving extra supplies. For his Smokejumpers book, Cole Barash was commissioned by the US Forest Service to make a series of photographs of the firefighters’ work, including “controlled burning”, a technique used in forest management that can burn up to 1,000 acres at a time.

SERVING

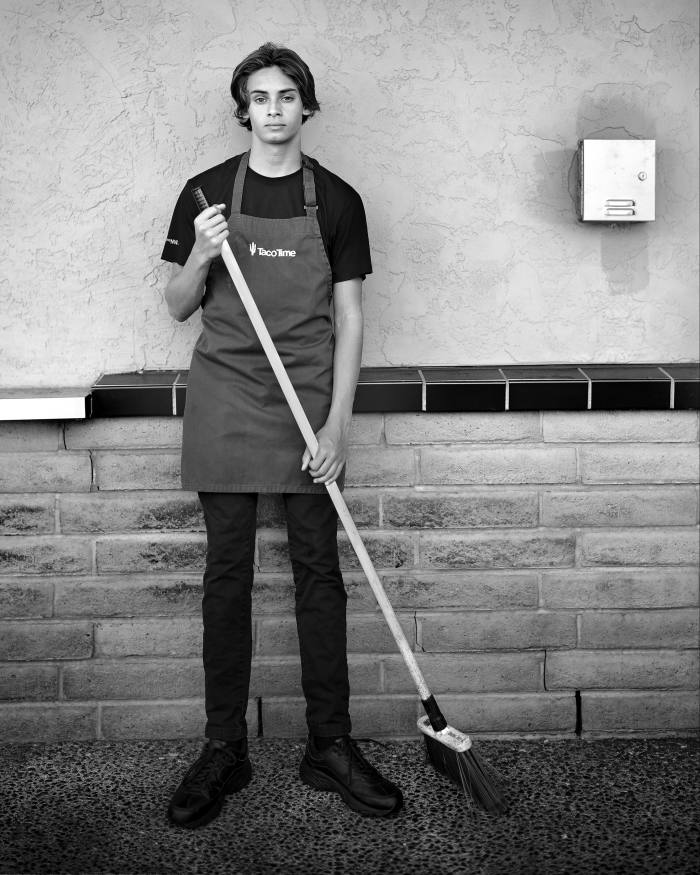

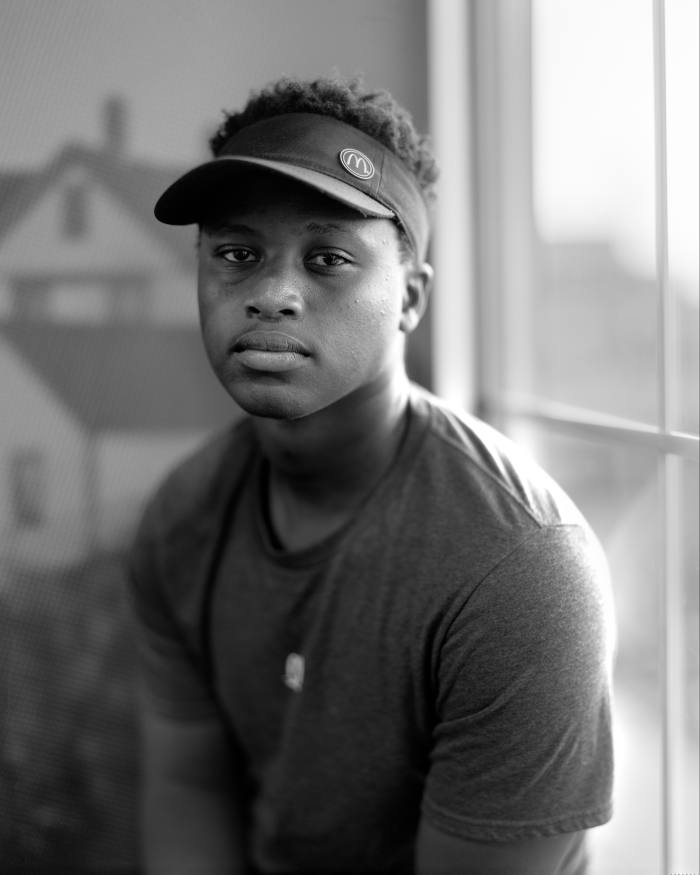

Richard Renaldi

Billions Served, 2019

Richard Renaldi has been photographing workers at fast-food restaurants in the US, including Taco Bell, Chick-fil-A, Dairy Queen and Wendy’s, since 2019. The result is a series of portraits titled “Billions Served”. Apart from the workers’ first names and locations, he does not give any information about them or their motivations. He says he would rather let their postures, expressions, surroundings and dress communicate the emotional and physical experience of working in these environments.

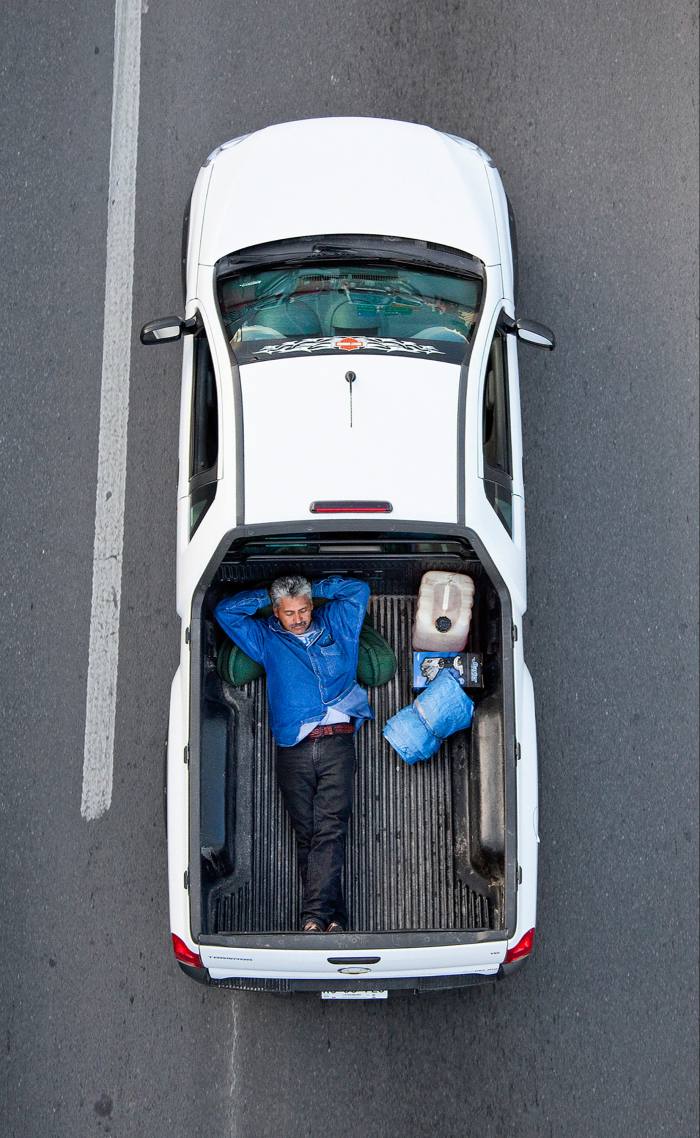

Alejandro Cartagena

Carpoolers, 2011-12

I made “Carpoolers” over the course of a year, standing on overpasses on Monterrey’s Highway 85 and capturing workers travelling south to one of the richest cities in Latin America, San Pedro Garza García. In Mexico, for more than a decade, the government has tried to tackle the housing crisis by subsidising the building of suburbs far from urban centres, causing long commutes and increased fuel consumption. I first noticed the carpoolers on an earlier project photographing urban landscapes. Public transport is lacking, so people cobble together sometimes dangerous solutions to reach work. But I found their determination uplifting. Mexico can be a hard place to live; these guys are staying honest and legit, which is something to admire. And even though they’re probably not conscious of the ecological impact of travelling this way, they are silently contributing to the preservation of our city and planet. —AC

Hajar Benjida

Atlanta Made Us Famous, 2018-ongoing

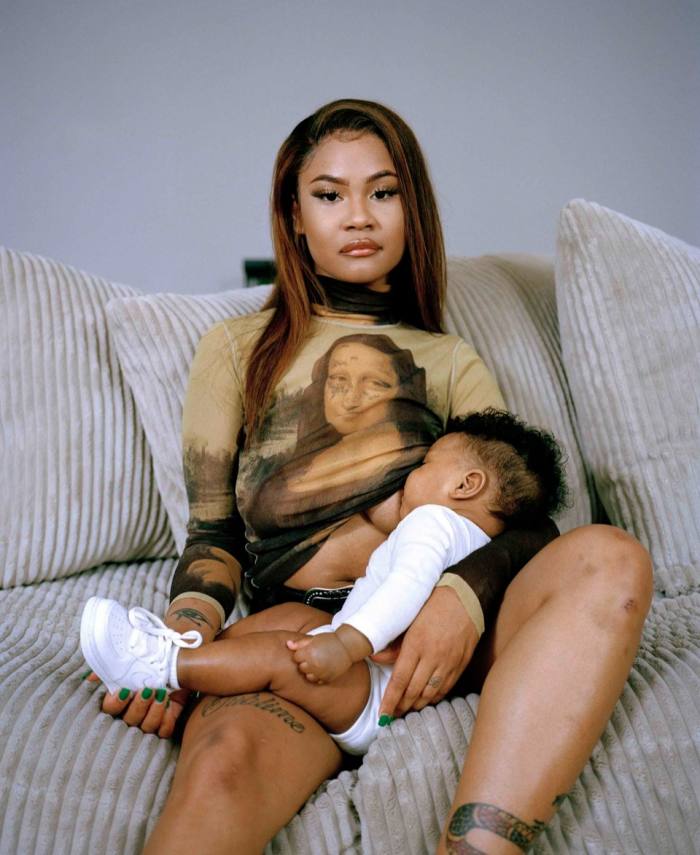

To the casual passer-by, the Magic City strip club in Atlanta, Georgia appears distinctly ordinary. The small grey building is perched on the side of a busy road, a glowing neon over the doorway. But to those in the know, it’s a place where hip-hop history was made. It was once visited by 2Pac and Biggie, and has since hosted performances by Young Thug and 2 Chainz. On her first visit to the club in 2018, the photographer Hajar Benjida found herself drawn not to the music industry names who frequent it, but to the dancers who entertain them. Her project “Atlanta Made Us Famous” captures brief moments in the lives of these women — dancers, mothers, wives, breadwinners — each posing as a famous musician might, offering a mix of fierce confidence and palpable vulnerability. Distinct from the club’s prevailing male gaze, Benjida presents an insight into the dancers’ respective worlds. “I hope to show that their images hold power and importance beyond hip-hop and its surrounding culture,” she says. “From my perspective, it’s the dancers that shine as the stars of the city.”

“Atlanta Made Us Famous” is at TJ Boulting until January 28; tjboulting.com

Sabelo Mlangeni

Invisible Women, 2006

In 2006, Sabelo Mlangeni spent eight months accompanying municipal workers as they cleaned the streets of Johannesburg at night. “Invisible Women” is the result. Mlangeni grew up in Driefontein, a village some 300km east of Johannesburg, and was fascinated by the city’s demands and rhythms. As he later told the journalist Sipho Mdand, the women did not initially trust him and were worried that his attention on their jobs could backfire. But over time he built a rapport with them, hearing their stories and helping with their work. They did not want to sweep the streets in darkness while their families slept at home but needed the money to feed their children. It often created problems at home as household chores piled up and schedules clashed, with mothers leaving for work in the evening just as their children were returning from school.