When death row speaks

It comes truly from the heart

It’s a lonely situation

The frustration’s just a start.— Willie Manning

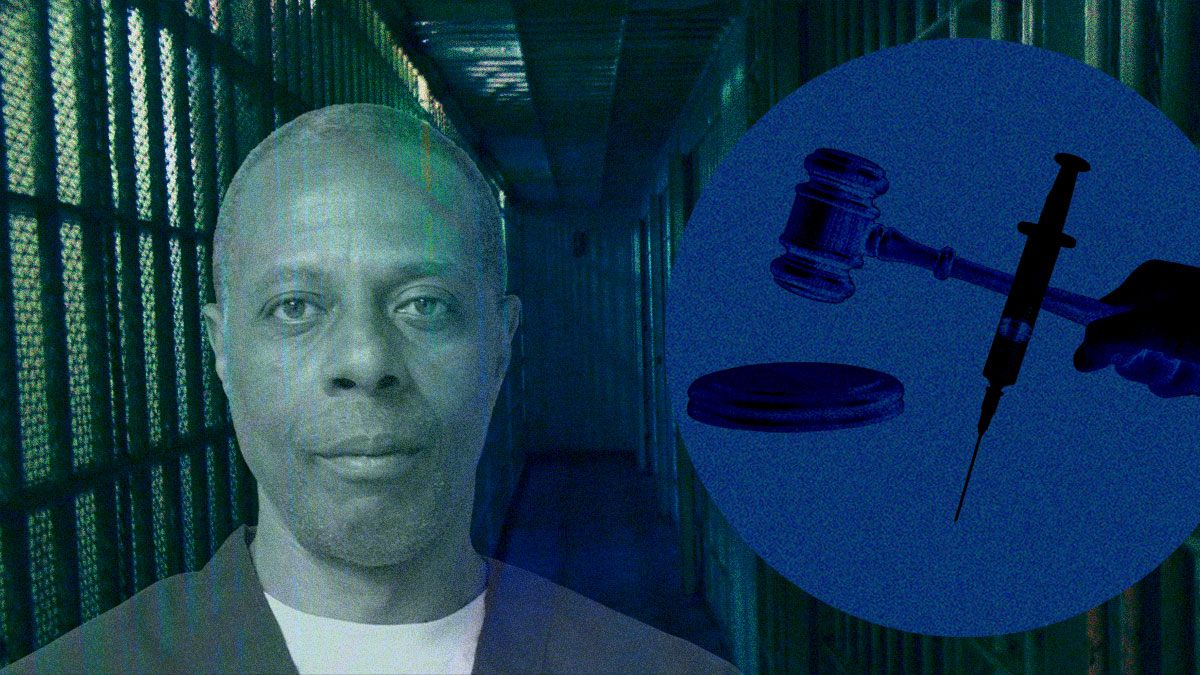

Unless a court intervenes, the state of Mississippi will execute Willie Manning, despite the fact much of the case against him has crumbled.

If the Mississippi Supreme Court doesn’t give Manning another hearing, justices are expected to grant Attorney General Lynn Fitch’s request to set an execution date.

He remains on death row, convicted of the 1992 murders of two Mississippi State University students, Jon Stephen Steckler and Pamela Tiffany Miller, but the scientific evidence that helped convict him has gone up in smoke.

At trial, an FBI examiner told jurors that bullets fired into a tree, allegedly by Manning, matched those used to kill the couple to the exclusion of all other guns. The FBI later said such a conclusion was not supported by scientific standards.

Another FBI examiner testified that hairs found in Miller’s car belonged to someone Black. Steckler and Miller were white, and Manning is Black. The FBI later called such hair analysis invalid.

Beyond such evidence, the jailhouse informant who implicated Manning has since recanted.

“In this case, there are no fingerprints, fibers, DNA, or other physical evidence linking Manning to the murders or the victims,” wrote Manning’s defense team, which includes attorneys David Voisin and Robert Mink Sr. as well as Krissy C. Nobile, director of the Mississippi Office of Capital Post-Conviction Counsel. “All that remains in his case is recanted testimony and debunked forensic science.”

Fitch said Manning needs to be executed.

“The Court should not allow Manning to abuse the system by citing inapplicable rules, raising baseless claims, and incorrectly relying on this Court’s precedent to further delay execution of his lawful punishment,” she told the justices. “This Court should reject Manning’s latest attempt to further delay execution of his lawful sentence imposed thirty years ago.”

Two double homicides

Two weeks before Christmas in 1992, Mississippi State students were celebrating the end of final exams when the bodies of 19-year-old Steckler and 22-year-old Miller were found on a blood-spattered road at 2:15 a.m., a little more than an hour after they were last seen leaving Steckler’s fraternity house.

Steckler had been shot and run over by Miller’s car. She had been shot twice, and one leg was out of her pants and underwear, but authorities found no evidence of sexual assault.

A month later, the bodies of 90-year-old Alberta Jordan and her 60-year-old daughter, Emmoline Jimmerson, were found slashed to death in their apartment in Starkville.

Both double homicides went unsolved.

The couple’s murders took place on the same night that Steckler’s fraternity brother, John Wise, had his Chrysler Eagle Talon burglarized. He said several items were stolen from his car: a CD player, a silver huggie, a leather bomber jacket and $10 in change, plus a restroom token. Steckler’s watch, gold necklace and Cathedral High School class ring were also missing. So was Miller’s ring.

Wise identified the token found at the murder scene as identical to the one taken from his car, and authorities theorized that Steckler and Miller had interrupted a burglary outside the fraternity house.

In April 1993, firefighters in Starkville found a silver huggie, which Wise identified as his. At this point, Manning became a primary suspect, Oktibbeha County Sheriff Dolph Bryan testified, but he didn’t explain why. Manning lived out of town, five miles from where the huggie was found.

A month later, the sheriff arrested Manning, previously convicted of burglary, robbery and grand larceny, and charged him with both double homicides.

A day later, the sheriff got a visit from Earl Jordan, who was back in jail after spending more than two years in prison. He had been on the sheriff’s list of suspects because he and another man had reportedly barged into a fraternity house, swiped cash, threatened to steal a car and said, “We are not afraid to kill anybody.”

He told the sheriff that his cousin, Manning, had admitted burglarizing a car with another man, that they forced Steckler and Miller into her car, drove them to a remote location and killed them.

Jailhouse snitches seeking deals

Manning went on trial for the murders of Steckler and Miller.

Witnesses testified that Manning attempted to sell a ring and watch matching the general description of Steckler’s missing jewelry.

Wise testified about the items stolen from his car and identified the token found at the murder scene as identical to the restroom token stolen from his car. One witness said Manning sold him a CD player, which matched the serial number of Wise’s CD player.

Manning admitted he fenced the CD player, according to the sheriff’s notes, but he repeatedly denied being responsible for the couple’s murders.

At trial, two jailhouse informants told the jury, made up of 10 white and two Black jurors, about statements they said Manning had made. Jordan testified that Manning confessed to the murders, and Frank Parker said he overheard Manning talk about selling a gun.

Manning’s former girlfriend, Paula Hathorn, told jurors that Manning fired a gun into a tree in the yard, and FBI examiner John Lewoczko concluded that those bullets matched the ones that killed the couple “to the exclusion of every other firearm … in the world.”

Hathorn told jurors Manning didn’t come home for days after the shooting and gave her a leather jacket, which Wise identified as his.

In closing statements, District Attorney Forrest Allgood pointed at the babyfaced Manning. “He doesn’t look like a blood-thirsty monster,” he said. “Monsters never do.”

The jury convicted Manning.

A day later, the defense lawyer begged for his life, saying vengeance belonged to the Lord.

Allgood said Manning deserved execution for murdering these young students. “They were living bright with promises,” he said. “They were bright with dreams of tomorrows that went on forever. Now they are so much rotting flesh.”

If this “slaughter,” he said, “doesn’t justify the death penalty, then we need to apologize to every other individual on death row.”

The jury agreed, and the judge sent Manning to prison to be executed.

Witnesses recant

Over a five-year period, Hathorn had wracked up 88 bad check charges.

At the time of the murders, she faced 33 of those charges and owed $10,000. Worse than that, she faced up to 10 years in prison.

When she mentioned possible time behind bars, she said Sheriff Bryan told her, “You ain’t going to have to worry about that.”

The sheriff picked her up sometimes and bought her Church’s chicken. She said he also bought her furniture and paid some of her bills.

The sheriff wrote out questions for her to ask Manning and recorded all of her conversations with him in person and over the phone. The defense never knew about these recordings in which Manning said he had nothing to do with the murders.

Before testifying, she said the sheriff coached her, and after the conviction, he took her to the bank and gave her $17,500 in reward money. Authorities dropped all but one of her charges.

She told jurors that she saw him on Dec. 9, 1991, but she did not see him again until Dec. 14.

In a 2023 sworn statement, she said she saw him the day of the Dec. 11 killings. They were both at his mother’s house, which didn’t have running water. They had to boil water on the stove and wash in the sink.

“I never saw Willie Manning with any clothes that had blood on them,” she said, “and I never saw him trying to clean blood off him or off any of his clothes.”

As for Jordan, he initially pointed his finger at two suspects in the murders and passed a lie detector test.

Authorities ruled the men out and arrested Manning. A day later, Jordan told the sheriff that Manning had described carrying out the burglary and murders with Jessie Lawrence.

The problem? Lawrence was in an Alabama jail that day.

There was a logistical problem as well. How did four people cram into Miller’s two-seater sports car?

After Manning’s conviction, Jordan received reward money and pleaded guilty to a reduced charge. He admitted he lied in 2012, but he wouldn’t sign anything until 2023 when the sheriff and district attorney were both out of office.

“Manning never told me he killed anyone,” he said in a sworn statement.

He said he lied at the time because he knew he could have been charged as a habitual offender. When the sheriff shared details about the murders, “I changed some words to the way the sheriff said he thought it happened,” Jordan said. “The sheriff was satisfied.”

At trial, jailhouse informant Frank Parker testified that Manning talked to his cellmate about selling a gun, but that cellmate, Henry Richardson, denied that Manning ever spoke to him about a gun. “All we did was play cards,” he said.

In a sworn statement, Parker’s uncle, former law enforcement officer Chester Blanchard, called his nephew a thief and a liar. “I would not take his word for anything,” he said.

In other statements, two men described seeing Manning at the 2500 Club close to midnight on the same night the murders took place. One said Manning asked him for a ride home, which he declined to do.

In another statement, a woman described parking at the apartments besides Miller’s sports car at 1 a.m.

Manning’s lawyers said this narrow timeframe, combined with his lack of a car, made it impossible for him to have carried out the murders more than 3 miles away.

The lone potential link between the burglary of Wise’s car and the murders was the token found at the murder scene.

Manning’s lawyers questioned whether the token came from Wise’s car since he testified his token was “dirty” while the sheriff described it as “a bright shiny gold colored coin.” A photograph of that token mirrors the sheriff’s description.

These tokens were produced for two service station restrooms in Mississippi as well as other restrooms across the U.S.

Hathorn said the sheriff gave her a much different reason for the murders. She said he drove her out to the gravel road where the killings took place and told her, “It was a drug deal gone bad.”

Manning’s lawyers have wondered if the killings might have been carried out by someone she knew. Miller was shot twice in the face at close range, which might suggest a personal killing. Her sports car was double-parked at an apartment complex not far from her trailer, and her missing ring was found between that trailer and her car.

One woman told police that on the night of the murders, she heard a man yelling after midnight from the direction of Miller’s trailer. Defense lawyers obtained statements from two people who said they heard what sounded like a white man yelling, followed by two gunshots.

Dashed hopes

In 2004, Manning learned he was getting a new trial.

It was the first good news he had heard in years. He had two different lawyers appointed to handle his post-conviction relief in Mississippi. They failed to file anything, and the statute of limitations for filing expired in federal court.

After the state Legislature created the Capital Post-Conviction Relief office in 2000, Voisin and Mink both took on the case and filed Manning’s first post-conviction relief request.

That filing led the Mississippi Supreme Court to conclude that prosecutors at Manning’s trial had been guilty of reversible error because they tried to enhance Jordan’s credibility as a witness by asking him if he had volunteered to take a lie detector test.

Justices had recently reversed a criminal case for the exact same reason. Now they reversed Manning’s conviction.

Lawyers for the attorney general’s office asked the high court to reconsider its ruling. They called the evidence against Manning “overwhelming” and suggested that the court adopt the U.S. Supreme Court’s limited retroactive standard.

In 2006, the justices followed the attorney general’s advice, reversed their original decision, took away Manning’s hope for a new trial and sent him back to death row.

Voisin called the ruling baffling. “Prosecutors improperly bolstered his [Jordan’s] credibility,” he said, “and we can’t get a hearing.”

Reprieve with four hours to spare

On the morning of May 7, 2013, Manning prepared to be executed. Tonight would be his final meal when he could dine on steak, shrimp or anything else he fancied. He found it strange that they would feed him so well just before they killed him.

Four hours before the 6 p.m. execution, word came that the Mississippi Supreme Court had issued a stay in an 8-1 vote.

Days earlier, the state had received letters from Justice Department officials, who said the ballistics tests were in “error” and that an FBI examiner had overstated conclusions about hair analysis by saying the hair came from an African American.

After halting the execution, justices reversed their denial of a defense request to reexamine a rape kit, fingernail scrapings, hairs and fingerprint evidence in the case. The rape kit again yielded no DNA.

Authorities identified 33 fingerprints inside Miller’s Toyota MR2. Sixteen belonged to Miller or Steckler, but none of them matched Manning.

In hopes of finding other matches, defense lawyers ran the fingerprints through a database known as the Automated Fingerprint Identification System. None was found.

DNA tests on the rape kit provided no additional clues, either.

After raising money to pay for a lab to test the hair from Miller’s car, the hair fragments proved too small and degraded to obtain a DNA profile.

A specialized lab told defense lawyers that it could do the testing, but Circuit Judge Lee J. Howard IV rejected that request because it had taken longer than three years and because “identifying the mitochondrial DNA of seven hair samples obtained from vacuum sweeping and debris from the car will not call into question [Manning’s] conviction as it is irrelevant to the issue of guilt.”

The Mississippi Supreme Court backed that rejection, saying even if another DNA profile was “discovered from the crime scene evidence, no proof has been shown that it would change the outcome of Manning’s case,” Justice Robert Chamberlin wrote.

After avoiding execution, Manning returned to his death row cell and resumed what he had been doing for decades. Waiting.

He penned a poem:

How many times have I shed tears?

How many people have to die

Before this nation starts to realize

That this system’s all a lie?

Another death penalty, more witnesses recant

In 1996, Manning went on trial for the murders of Jordan and Jimmerson.

Kevin Lucious said that he and his girlfriend, Likeesha Harris, and their baby lived in the same apartment complex as the victims.

Lucious told jurors that he saw Manning push himself into the victims’ apartment and later tell him if he had known “they” only had $12, he would not have done anything to them.

The jury convicted Manning, and he was sentenced to death.

In a 2011 evidentiary hearing, Lucious, who was serving three life sentences in Missouri, recanted his testimony against Manning, saying he was afraid he would be charged with the murders.

The apartment where Lucious testified that he lived with his girlfriend was actually vacant at the time the killings took place. The Starkville police knew this, but concealed the information from both prosecutors and defense lawyers.

The girlfriend, Harris, testified that as soon as she read in the local newspaper about Lucious’ testimony, she knew it wasn’t the truth. “Kevin was trying to get himself off by any means necessary,” she said. “He lied.”

In a 7-2 vote in 2015, the Mississippi Supreme Court granted Manning a new trial because the state withheld critical information.

“Any attorney worth his salt would salivate at impeaching the State’s key witness using evidence obtained by the Starkville Police Department,” Justice Michael K. Randolph wrote.

Manning’s attorneys never got a chance. Prosecutors dismissed his charges before a new trial ever began.

That dismissal marked the sixth exoneration in the same judicial district, according to the National Registry of Exonerations. All the cases came under longtime district attorney, Allgood, featured in Netflix’s documentary series on cases of wrongful convictions, “The Innocence Files.”

“These numerous wrongful convictions stemming from the same judicial district and prosecutor fit a template: flawed and false forensics and-or official misconduct,” Manning’s defense team wrote. “Manning’s current case follows that template.”

All but one of those exonerated were Black.

Sheriff Bryan denied in testimony that race played any role in the investigation, but he acknowledged creating a list of 13 possible suspects in the murder. All of them were Black.

Black Americans are seven times more likely than white Americans to be wrongly convicted of serious crimes in the U.S., according to a report by the National Registry of Exonerations.

Of the 29 Mississippians exonerated since 1989, 83% were Black. In fact, Black Americans convicted of murder are about 80% more likely to be innocent than other Americans convicted of murder.

As for false testimony, evidence shows it can often lead to wrongful convictions. Studies show that nearly two-thirds of wrongful murder convictions since 1989 have resulted from false testimony, and nearly half of wrongful capital convictions have resulted from the false testimony of informants.

“The witness intimidation and false testimony in the Jordan-Jimmerson case was an intended feature, not a ‘flaw,’” lawyers Ayanna Hill and Thomas M. Fortner wrote in a friend of the court brief for the ACLU, the NAACP and the Mississippi Office of State Public Defender. “When law enforcement is willing to frame a man twice for murder, it is almost beyond question that more aspects of Mr. Manning’s trial would fall far short of what he was constitutionally entitled to.”

What is justice?

Manning, now 56, sits on death row. Unless a court intervenes, he will be strapped down and injected with a drug to stop his heart.

The same Mississippi Supreme Court that tossed out his conviction in one case is denying him a new hearing in the other. In a 5-4 decision, the chief justice called the evidence against Manning “overwhelming,” saying even Jordan’s recanted testimony “would not have changed the verdict.”

Manning “has had more than a full measure of justice,” he wrote. “Tiffany Miller and Jon Steckler have not. Their families have not. The citizens of Mississippi have not.”

In his dissenting opinion, Presiding Justice Jim Kitchens wrote, “Today the Court perverts its function as an appeal court and makes factual determinations that belong squarely within the purview of the circuit court judge.”

Without Jordan, the case against Manning is circumstantial, and this is why a circuit judge needs to hold a hearing on the truthfulness and timeliness of the recanted testimony, he wrote.

Mississippi’s attorney general said it’s time for Manning to face justice and called on the high court to set an execution date.

His “fruitless trip to the circuit court for DNA testing brought the litigation of this case to an end,” Fitch wrote. “Manning’s pending motion is a blatant attempt to delay his lawful execution.”

Former District Attorney Allgood agreed. “There are a lot of deserving individuals for the death penalty,” he said. “[Manning is] certainly one of them.”

Former Sheriff Bryan could not be reached for comment.

Manning’s defense team said if the state of Mississippi goes forward with his lethal injection, it will execute an innocent man.

“What measure of justice is served if the wrong man is put to death?” the lawyers asked. “Will Mississippi allow a man to be executed when it has been proven that corruption, coercion, and false forensics lie at the core of his conviction and death sentence?”