[ad_1]

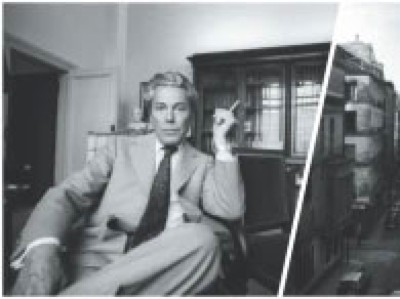

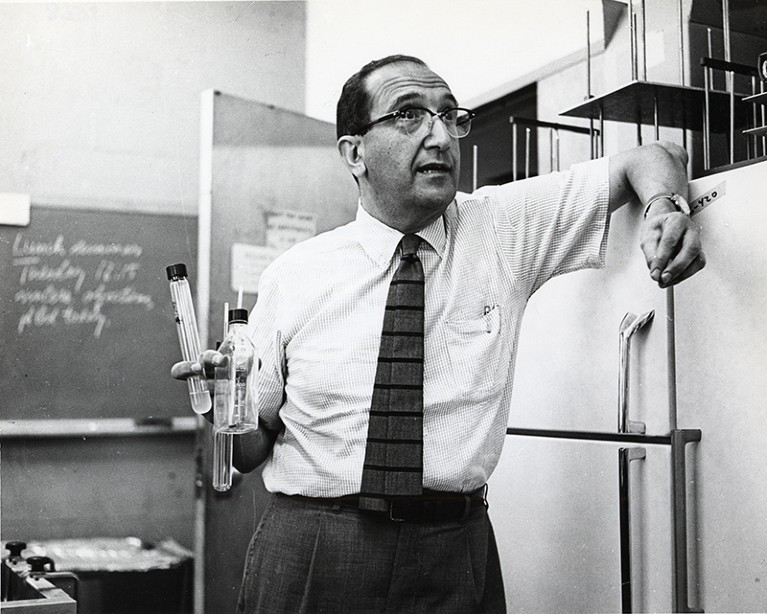

Salvador Luria at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology around 1970.Credit: Science History Images/Alamy

Salvador Luria: An Immigrant Biologist in Cold War America Rena Selya MIT Press (2022)

Microbiologist Salvador Luria was a man of firm political convictions. The day before he won a share in the 1969 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, he talked to state legislators in Massachusetts, attended a peace convocation at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge and joined a protest against the Vietnam War. The FBI had begun monitoring him a few years after he arrived in the United States in 1940, fleeing fascist Italy. The Nobel didn’t stop them.

Luria shared the prize with Max Delbrück and Alfred Hershey for research on bacteriophages, viruses that invade and often kill bacteria. This work tilled the ground for the fields of bacterial genetics, virology and molecular biology. Science historian Rena Selya distils his story in her well-researched Salvador Luria.

Luria’s life began serenely, in Turin in north-west Italy. Benito Mussolini came to power ten years later, in 1922, but Luria’s middle-class Jewish family “lived passively” in the fascist regime. Luria got his first taste of research at medical school in Turin, in the laboratory of Giuseppe Levi, a hot-tempered anatomist who knew how to pick his students. Renato Dulbecco and Rita Levi-Montalcini, who joined the lab the next year, also went on to win Nobels.

Molecular genetics: A revolutionary meeting of minds

Luria excelled but was bored by cataloguing cells. Eighteen months of national service as a junior medical officer in Mussolini’s army put him off practicing medicine. Instead, he was drawn towards physics and the work of geneticists who were using radiation to induce mutations in model organisms.

So, in 1937, Luria joined Enrico Fermi in Rome. In 1938, Fermi won the physics Nobel; that year, Mussolini introduced laws excluding Jews from public offices and higher education. In December, Fermi and his Jewish wife travelled from the Nobel ceremony in Stockholm to America. Luria left Italy for Paris. There, he learnt how to culture bacteriophages and to measure them using radiation.

In Paris, Luria also began his engagement with politics. He associated with other Italian refugees (including atomic physicist Bruno Pontecorvo, who later joined the US atomic bomb project, but defected to the Soviet Union in 1950) and read Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Vladimir Lenin and more. He committed to socialist economic ideals. (Later, he became a feminist, living by the maxim ‘the personal is political’ and sharing household tasks equally with his wife.)

After the Nazis invaded France in May 1940, he fled Paris by bicycle, with Pontecorvo and others. Regrettably, Selya provides only a brief sketch of this dramatic escape to the south of France, through Spain to Portugal, where he was finally granted US immigration papers. She notes that the drama included being shot at from planes and hiding in an abandoned farmhouse with the Italian writer Carlo Levi. From Lisbon, Luria travelled in a ship packed with refugees, reaching New York City on 12 September, with US$52 in his pocket.

Within months, he had met and bonded with Delbrück, who was about to take up a post at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York. The physicist-turned-biologist was keen to use bacteriophages in genetic research. By 1943, Luria had his first tenured position, at Indiana University Bloomington.

When business became biology’s plague

During the 1940s, he and Delbrück revealed that some bacteria are resistant to phage attack. How the resistance arose, Luria settled in a simple, ingenious experiment inspired by slot machines’ random jackpots. He filled test tubes with bacteria from the same stock, and left them to multiply. Only a few of the tubes became resistant to bacteriophages: Darwinian evolution in action. He and Delbrück developed the work into a classic paper (S. E. Luria and M. Delbrück Genetics 28, 491–511; 1943).

After the war, the US government invested heavily in basic research. Bacteriophages became a fundamental research organism. The field exploded. James Watson, who would later co-discover the structure of DNA, became Luria’s PhD student, and Luria brought Dulbecco over from Turin as a research associate.

More discoveries followed. Luria showed that phages can mutate, sometimes in tandem with their bacterial hosts. He showed that bacteria can sometimes render a lethal phage temporarily incapable of infecting further bacteria of the same strain, but still able to infect and kill other strains. Later research showed that these transient changes were due to bacterial restriction enzymes that target short strands of DNA. The enzymes became key molecular tools.

As Luria’s success grew, so did his political involvement. He campaigned for racial desegregation and workers’ rights. He supported Democratic candidates for Congress. He protested against the biological and nuclear weapons. He lobbied for academic freedom when the congressional House Un-American Activities Committee tried to impose anti-communist legislation on universities.

The FBI paid attention. Selya’s description of the United States during the cold war has eerie similarities with communist East Germany. The FBI recruited friends and colleagues to dish dirt; Selya obtained the reports through the Freedom of Information Act. Most informants commented on Luria’s liberal-mindedness but fell short of alleging that he was a member of the Communist Party. The agency illegally monitored his post, Selya writes. Most suspicious were two letters from New York, signed ‘SA’. The sender? The magazine Scientific American.

FBI officials interviewed Luria about Pontecorvo, with whom he had minimal contact in the United States. They questioned others about Luria’s loyalty, including physicist Ugo Fano, a childhood friend who had fled Italy in 1939 and helped Luria when he arrived (another section of the book where brevity left me with questions). In 1952, Luria was denied a passport to attend a scientific meeting in Europe and to visit his ill mother. (He finally got one in 1959.) He was also barred from federal funding review panels.

In 1950, he had joined the University of Illinois, but its policy of not employing spouses meant Luria’s wife, psychologist Zella Hurwitz, could not work there. When she won a post in Boston, Luria transferred to MIT. There he modernized the biology faculty and research played second fiddle to administrative duties.

One thing irked many of Luria’s illustrious colleagues in the 1980s: his criticism of the proposed Human Genome Project. He feared it could be abused for eugenic purposes. In an interview decades later, Watson called this proof that Luria “cared more about politics than science” (ironic given the prejudice that Watson is now infamous for).

Still, in a Nature obituary in 1991, Watson wrote of Luria: “there were few who did not feel better by being in his presence”.

[ad_2]

Source link