The signing of a licensing deal late last year for South Africa’s Aspen Pharmacare to bottle and sell the Johnson and Johnson Covid-19 vaccine across Africa was hailed as a lifeline for a continent that lost out in the rush for jabs early in the pandemic.

But six months later, the factory is on the brink of closure because of lack of demand.

Asked if she will get a booster shot after receiving two Pfizer jabs last year, 70-year-old Agnes Mohale could not see the point. “I don’t know what it’s for,” said the pensioner who lives in Johannesburg’s biggest township, Soweto. “I won’t go for a third one. I’m not worried.”

Mohale’s reluctance to seek extra protection reflects faltering demand in South Africa, where only 5 per cent of people have received a booster shot and just under a third of the 60mn population are double vaccinated. It is part of a broader trend across Africa that helps to explain why the future of the continent’s biggest vaccine manufacturing plant is in doubt.

The death toll from Covid-19 has been lower across Africa than other continents. Africa has accounted for just 8.3 per cent of the world’s 14.9mn excess deaths during the pandemic, according to a World Health Organization analysis, despite having 16.7 per cent of the global population. Some experts say the low death rate could be due to Africa being the youngest continent, with a median age of 19.7 against 42.5 in Europe.

The resulting reluctance to get jabs — and poor health infrastructure — means Africa could continue to be blighted by the disease long after Covid has become endemic elsewhere and give rise to more potent new variants, experts say. Meanwhile, the possible loss of local vaccine production could leave the continent ill prepared for future diseases.

“This lack of momentum on vaccinations is affecting our dynamic state of readiness for the next variant or the next viral threat,” said Dr Ayoade Alakija, co-chair of the Africa Vaccine Delivery Alliance. “It is endangering the local and regional vaccine production efforts that have popped up . . . to ensure we don’t return to the stage zero of the pandemic.”

The struggle to remain commercially viable does not bode well for efforts to build up vaccine production. At the onset of the Covid pandemic, there were just four African countries with vaccine manufacturing capacity: South Africa, Egypt, Senegal and Tunisia. Now, there are 15 African nations with vaccine manufacturing projects in the works.

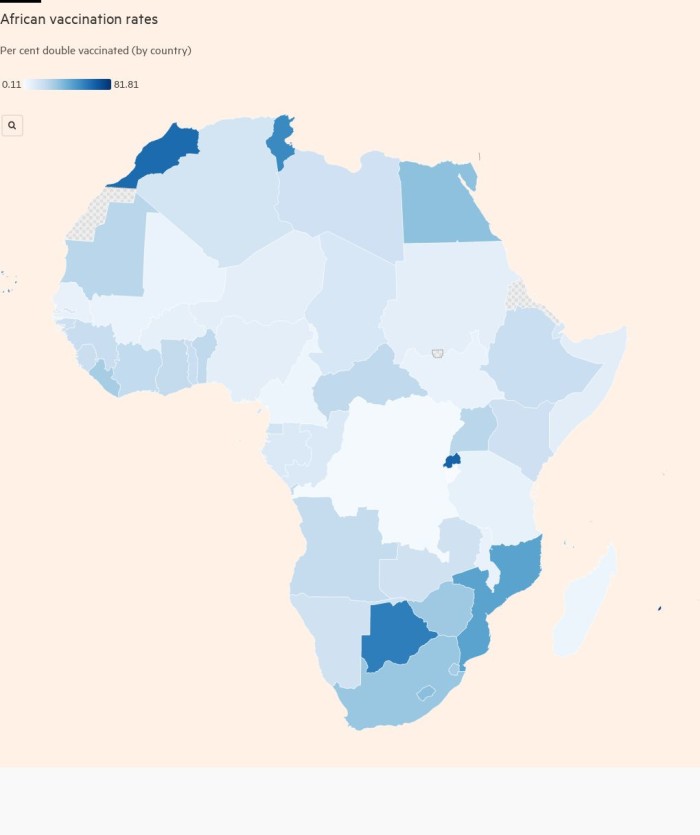

Just days away from the deadline of a World Health Organization target for countries to ensure 70 per cent of their population are double vaccinated against Covid-19 by June 2022, only two African countries — Mauritius and Seychelles — have achieved that goal. Morocco and Rwanda are nearing the 70 per cent target.

Only 17.4 per cent of Africa’s population is double-vaccinated, the lowest figure of any continent. Among European Union nations, the equivalent figure stands at 73.5 per cent.

Dr John Nkengasong, director of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, said the 70 per cent target for mid-2022 was “clearly not achievable for most countries in Africa” but should be the goal by the end of the year.

Privately, however, many public health officials think the target is now beyond reach due to vaccine hesitancy and the high levels of prior infection. A WHO analysis suggests around two-thirds of Africans may have been infected by the end of last year, even before the Omicron variant swept the continent.

A former high-ranking AU official involved in the body’s jab rollout admitted the goal of reaching 70 per cent vaccination coverage was no longer relevant for most African countries but had not been scrapped because “no one wants to be the first to say we’ve dropped it”.

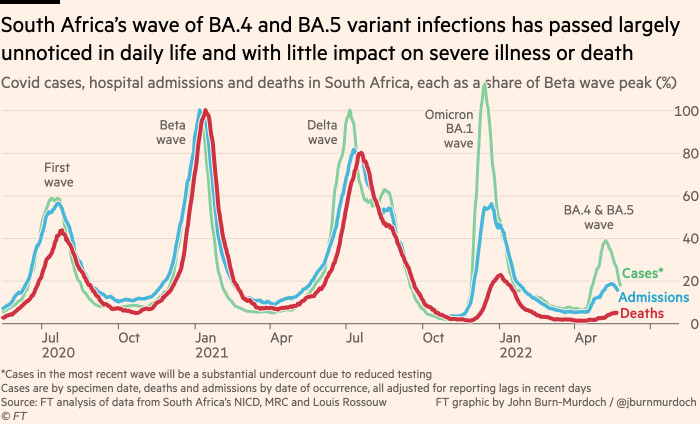

Demand in South Africa has tapered off because of “a sense of complacency” as Omicron infections seem to be less deadly, said Chris Vick, a public relations specialist with Covid Comms SA, a volunteer group working on vaccination communication.

A recent fifth wave of infections that was driven by two sub-variants of Omicron — BA. 4 and BA. 5 — peaked largely unnoticed in daily life and with little impact on rates of severe illness or death. “People are tired of it,” Vick added. “The importance of vaccination as a preventive measure is taken a lot less seriously than it was.”

The sense of fatigue is reflected across the continent, where public health officials have to juggle a wide array of problems. In Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, only 8.1 per cent of people are double vaccinated, with Ethiopia, the next largest country, faring better on 18.5 per cent but still well below the 70 per cent target.

“When you add together the low risk perception because of the way most Africans have been infected, when you add the mistrust, then definitely people will not run to get the vaccine,” said professor Yap Boum, a Cameroonian epidemiologist and the regional representative for Epicenter Africa, the research arm of Médecins Sans Frontières.

Covid-19 had “dropped way down the priority list” of health concerns in Africa, he said. “You have malnutrition in some countries, malaria, cholera, yellow fever, measles — why would you put Covid as a priority?”

In South Africa, the search for work also leaves little time for vaccination. Vaccination sites remain poorly advertised, are hard to get to, and close too early for workers and those in poor areas to reach them, surveys find.

“People stopped thinking of vaccination as a priority,” Vick said. The problem now is “how you bump it up the scale of social priorities”.

Thandiwe Mpofu, an unvaccinated face mask vendor in Soweto, said she was no longer concerned about Covid. “I was worried before — now it is just something we have to live with,” said the 36-year-old.

But Nkengasong stressed that despite waning demand to get vaccinated against Covid-19 across Africa, the local vaccine production cannot be allowed to fall by the wayside.

“Every region of the world, including Africa, should be able to produce vaccines in a timely fashion so that we don’t get into these squabbles of accusing the north of depriving the south of vaccines,” he said.