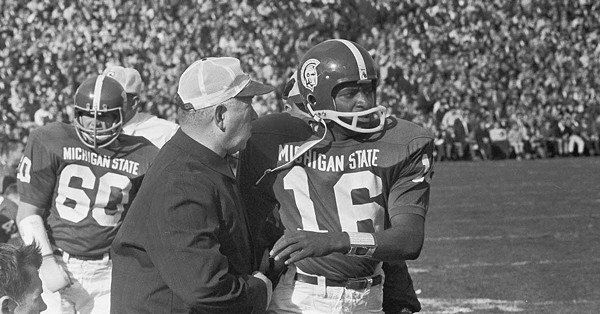

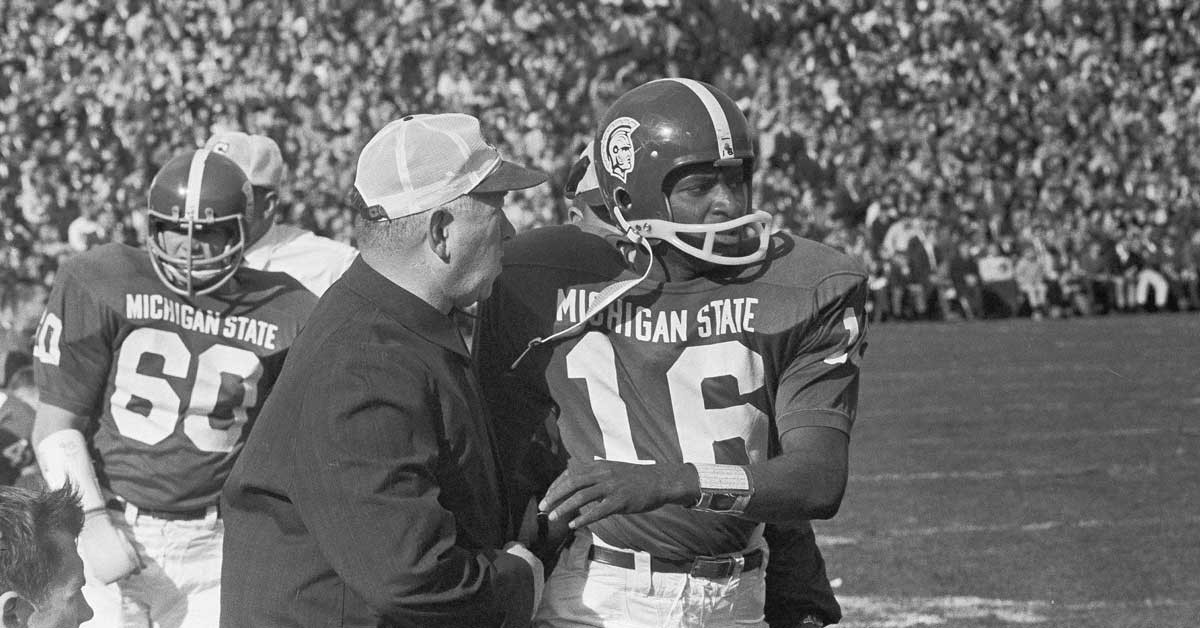

Usually, when the Underground Railroad is mentioned, images of Black Americans furtively fleeing enslavement in the South are invoked. A century later in 1966, the system and its heroic conductors such as Harriet Tubman took on new meaning for Michigan State’s football coach Hugh “Duffy” Daugherty (1915-1987) and the school’s president John Hannah (1902-1991) as they colluded to bring Black players out of the grip of Jim Crow laws and eventually aid the end of segregation.

Those momentous days were given a fresh gloss at a recent Michigan State Hall of Fame induction ceremony where the 1965-1966 football teams became the first teams to be inducted. More significantly, they were the first fully integrated college teams and thereby were instrumental in eliminating the racial barriers and forging a new era of college football. Daugherty spearheaded this movement by venturing to the South to recruit Black players.

Clint Jones, one of Daugherty’s recruits, said at the ceremony that, “What was accomplished here at Michigan State with the 1965 and ’66 teams was equivalent to Jackie Robinson, Rosa Parks, or any other paradigm shift that’s happened in the civil rights movement and also American history. And this is American history, not just Black history, but American history, and it is also unprecedented, of what happened in the time period that it did,” he said. “That’s something that for the most part is kind of an urban legend within Spartan Nation that has been revealed throughout the United States, as it should be. Anytime you have a paradigm shift like that it needs to be known and widely spread to the public.”

Jimmy Raye, the team’s quarterback — an underground passenger, so to speak, and the first of his race to lead a college team to a national title — amplified Jones’s memories about the coach, stating, “I think everything that Coach ‘Duffy’ Daugherty did was unique. I think it’s something that should definitely be recorded in history, and something that was on the precipice of integrating college football throughout the country and particularly the South where I came from, with the Jim Crow laws in effect, and Black athletes didn’t have an opportunity to play Division I level football at Southern schools. I think Coach ‘Duffy’ Daugherty should be recognized for his color blindness and his willingness to play and deal with the consequences of playing a fully integrated team. There are a lot of firsts that took place in that era at Michigan State, and I think that everything they’re doing now to recognize that will stand in the history of Michigan State Athletics for all time. I’m just very, very, very appreciative of that.”

Several organizations, institutions, and individuals have been tireless in their efforts to keep MSU’s gridiron heroes alive, including Maya Washington, the daughter of Gene Washington, whose documentary Through the Banks of the Red Cedar features Washington’s remarkable college and professional career, and noted Detroit attorney Greg Reed, who as a student at the college witnessed what the team accomplished and who attended the induction ceremony. “What they did was a defining moment in my life,” Reed said, “inspiring me to advocate for exploited athletes and artists as an MSU freshman engineering student. This pledge led me to law school… inspiring my transition into civil rights, representing revered figures from Rosa Parks, Malcolm X, Alex Haley, Nelson Mandela, Coretta Scott King, and Aretha Franklin, and six world champions, and grounding me in the principles of ‘know thyself,’ Nation of Islam, and ‘love thyself,’ as I embark on my next journey.”

Reed insisted that more needed to be known about the role Daugherty and President Hannah played in forging this historic development. Reed did champion a cause to have Congress to archive the team’s legacy for future generations. While Tom Shanahan offers some important insight in his book Raye of Light about the quarterback and Daugherty, turning to the source was even more rewarding as Daugherty in his autobiography (with Dave Diles) recalled the events.

“Recruiting was a lot easier back when schools in the North had the corner on black athletes,” he recalled. “For a long time, the major southern schools simply didn’t recruit the good black athletes. Coaches like [Alabama coach Paul “Bear”] Bryant would frequently let me know about an outstanding player of that type, and I’m proud to say that Michigan State was a forerunner not only in accepting but aggressively recruiting outstanding black scholar-athletes. Once the doors in the South were opened, though, it made things a lot more difficult.” (Shanahan debunked the myths that “Bear” Bryant sent Southern Black players to Daugherty.)

Among the engrossing moments in Daugherty’s reflections is his personal encounter with Charles Aaron “Bubba” Smith, and key to Daugherty’s early forages into the South. “Bubba’s father was a very successful high school football coach in Beaumont, Texas. We had tried to recruit Bubba’s older brother, Willie Ray, but he wound up at Iowa. Willie Ray wasn’t happy there and eventually left school. So when Bubba was a senior in high school, Mr. Smith called me and asked if we’d ‘take a chance on my boy Bubba and try to make a man out of him.’”

Daugherty speaks with delight and reverence about his players as well as his relationship with President Hannah, who had empowered Duffy with unwavering in his support of Duffy’s initiative. He recounted an incident: “There was a so-called Black Student Alliance on campus and there were some football players in that group,” he recalled. “Their concern was that there was not enough black involvement within the framework of the university — secretaries, administrators, cheerleaders, you name it. We had already hired a black assistant coach, but the BSA had some grievances in other sports. The committee took the matter to our athletic director, Biggie Munn, and told him frankly that unless meaningful steps were taken — and right now — they would boycott all spring sports. That meant spring football, too.”

Duffy continued, “Our black athletes missed one day of practice. I made no announcement of any kind, but everyone knew if they missed one more, that was it. President Hannah saved the day, as he so frequently did. Spring practice rules permit four practice days per week. Dr. Hannah asked if I could excuse the blacks from the next practice. My answer to him was that I thought that would work to the detriment of the entire squad. He said he thought the issue could be resolved if the black athletes could meet with our faculty representative, Dr. John Fuzak and Dr. Robert Green, former disciple of Martin Luther King Jr. The compromise solution was to call off practice for one day for everyone while the summit meeting took place. The problems were aired and solved, and practice resumed. Everyone was back on the field, and that was the extent of our so-called ‘black problem…’ My relationship with John Hannah is the most treasured of all those I have formed in nineteen years as a head coach.”

Many of the experiences connected with accomplishments of the Spartans in 1965 and 1966 were summoned from the past by the players and other speakers, and it was left to Jones to assemble the pieces. “Everyone from President Hannah to Ken Earley, our equipment manager, and everyone in between worked together for our team to succeed. We were nothing if we didn’t work together,” Jones said.

What they did on the gridiron ramified to the various sectors of society where activists were bravely involved in bringing about change, and few of them like Reed recognized how all the elements combined and helped expand and accelerate the march toward freedom and justice.