If you’ve recently received your property appraisal and your response is, “Holy @$%—this is nuts!” you’re not alone in your expletive-filled reaction. Many Texans have received eye-popping estimates of their homes’ appraised values. Residential appraisals are up 15 to 30 percent in Harris County, 20 percent in Tarrant County, 24 percent in Dallas County, 25 percent in Bexar County, and 53 percent in Travis County, and I could go on.

My partner and I bought our 1,100-square-foot home in East Austin in 2011 for $200,000—what seemed like a fortune at the time. The market value has soared since then, as our neighborhood has transformed from an obscure working-class enclave into a “hot” area of expensive modern farmhouses with Teslas in their driveways. Last year, the Travis County Appraisal District pegged our home’s market value at $428,032. According to the Notice of Appraised Value we received in April, that figure has soared to $656,039—a staggering 53 percent increase and exactly in line with the county-wide rise in values. When the notice arrived, I took a screenshot of the document and sent it to my partner with a simple note: “greeeeeat.”

After the sticker shock wore off, I made a more sober appraisal of my situation. The bottom line is my taxes (and yours, or your rent) may indeed go up this year, and the next, and the next. It’s just probably not quite as bad as it seems.

That’s good news, I think. I like good news. So how much will I pay?

Unfortunately, that’s impossible to say at this point. Many factors could alter your property tax bill before it comes due in the fall.

The first thing to understand is that the market value is probably not the amount you will pay taxes on. It’s what the county appraisal district thinks your house would sell for as of January 1 of this year. But most homeowners will benefit from exemptions, most notably the homestead exemption. Ultimately, you will pax taxes on what’s known as the “taxable value”—a figure that could be far less than the market value. I’ll walk you through it. First, let’s take a look at our Notice of Appraised Value.

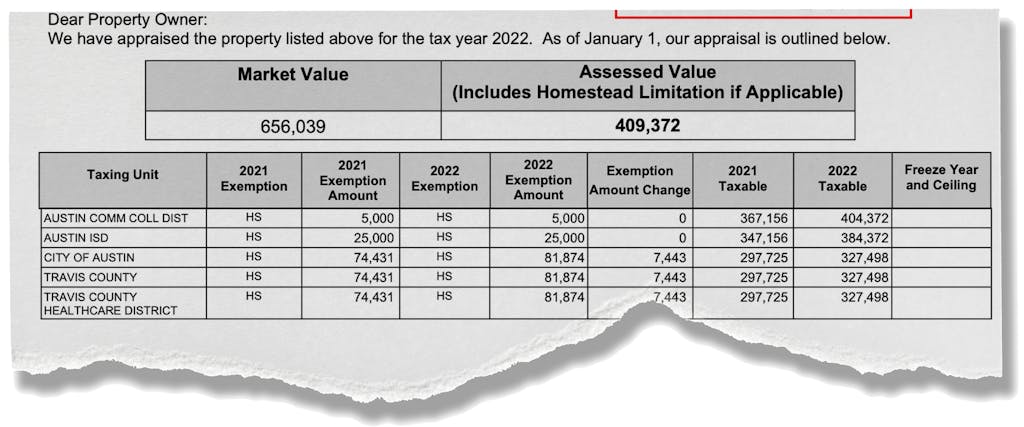

As you can see, there are two main numbers. First, the Travis County Appraisal District’s estimate of our home’s market value—$656,039. (We are now house-rich, cash-poor, it seems.) Second, the “assessed value” of our home after the district has applied one of the two benefits you get from qualifying for a homestead. According to state law, the taxable value for a homestead cannot increase more than 10 percent a year. That 10 percent cap is why our net appraised value for 2022 is preliminarily pegged at $409,372, not $656,039.

But that’s not the end of the story for us. Let’s take a look at our property taxes in 2021. (You can look up information on your appraisals via your county appraisal district website, but the terminology may vary from Travis County.)

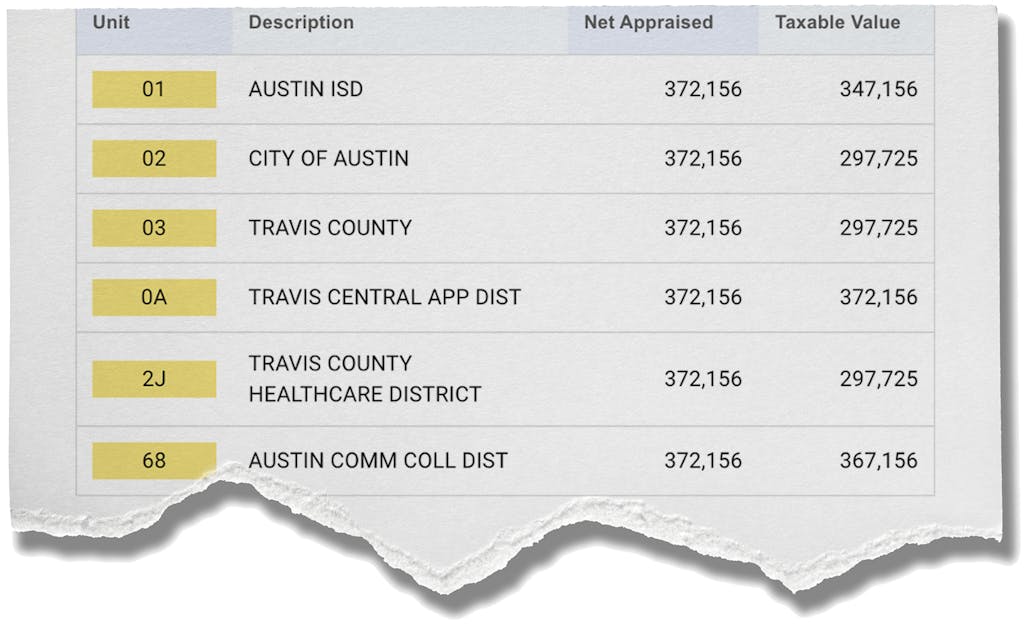

Above you will see two key terms—”net appraised” and “taxable value.” In Travis County, “net appraised” is equivalent to “assessed value”—it’s the value of your home after the 10 cap has been applied. But “taxable value” is what we really care about. That’s the actual dollar-amount you will pay taxes on for each taxing entity, and it takes into account all the other exemptions that apply.

Our home’s market value was $428,032 in 2021, but as you can see, we ultimately paid taxes on a much smaller amount: just under $300,000 for the city of Austin, Travis County, and the health-care district, and about $367,000 in the case of Austin Community College.

That’s thanks largely to our homestead exemption. In addition to the 10 percent cap, it also removes $25,000 of taxable value when it comes to calculating the taxes you’ll pay to your local school district, the lion’s share of your total bill. Take a look again at the screenshot above. For Austin ISD, you can see that the difference between the “net appraised” amount and the “taxable value” is $25,000—that’s the homestead exemption at work. (This exemption could rise to $40,000 if voters approve a constitutional amendment on May 7. In other words, an additional $15,000 of value would go untaxed. That works out to about $175 in savings for the typical taxpayer. See this Texas Tribune piece for the details.)

There are other exemptions too—for disabled Texans, for senior citizens, and for disabled veterans. In addition, taxing jurisdictions, such as school districts and cities, can apply an additional homestead exemption of up to 20 percent of the total value. (The cities of Austin, Dallas, Houston, and Fort Worth have all authorized the maximum 20 percent.)

But not everyone has a homestead exemption. In Tarrant and Travis counties, only about half of all residences are homesteaded. You get only one homestead exemption; second homes and investment properties don’t count. Most renters don’t live in a homestead residence, and many new homebuyers won’t enjoy the 10 percent homestead cap for at least a year, maybe two, depending on when they qualify for the exemption. Those folks will be much less insulated from the soaring market.

Bottom line: the “sticker price” in those appraisal notices is likely much higher than the amount you’ll eventually pay taxes on, particularly if you are homesteading.

What do you mean “eventually”?

These appraisal notices are merely an early step in the annual ritual of determining property taxes. First off, you have the opportunity to protest your appraised value. Many appraisal districts have online portals that make the process fairly easy and informal. If you’re not satisfied with the result, you can formally protest with your local Appraisal Review Board, which will hold a hearing. You, or a company representing you, will bring evidence to show that the appraisal district is overvaluing your property. Some experts say there is really no downside to protesting your appraisal.

“Every year is a good year to protest,” said Fort Worth real estate agent Chandler Crouch, who says he helped 22,000 Texans with their protests last year. “But this year, especially, you have to make sure that you’re not overpaying.”

Crouch and other experts expect a record number of protests this year, but appraisal boards are still subject to a state-imposed deadline of July 25 to wrap up their work. They have a ton to do and not much time. That could tip the advantage to the protester. One caveat: if the gap between your appraised value and your homestead-limited value is very large, then a protest may not matter this year. For example, in Travis County most property owners are seeing a 50 percent gap between their market and assessed values. “If you’re not getting below that assessed value, then your tax bill is not going to be adjusted at all,” Travis County chief appraiser Marya Crigler said recently.

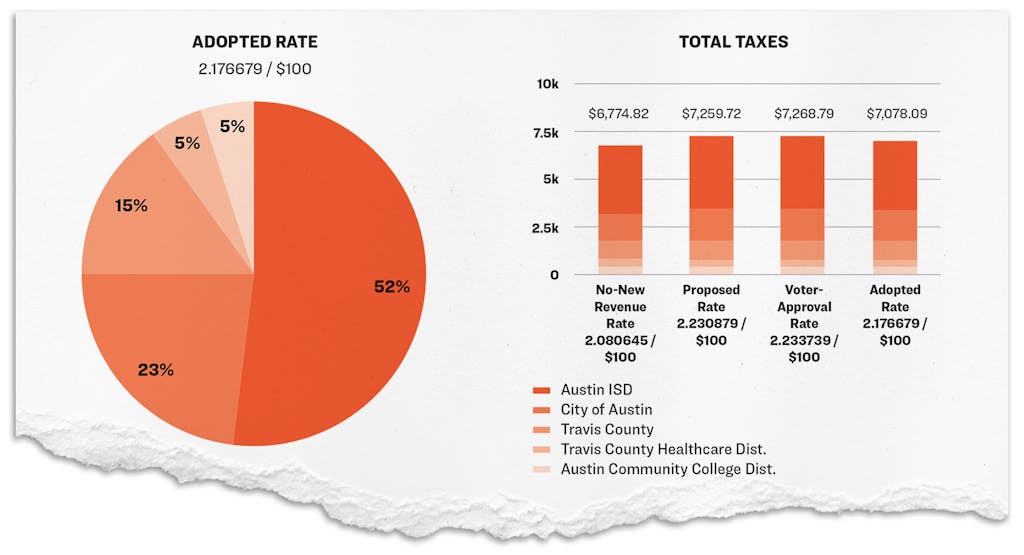

After protest season—which runs from now until late July—comes the next major phase of this delightful process. Texas’s local taxing jurisdictions—school districts, cities, counties, community colleges, hospital districts, etc.—will set their tax rates by the end of September. You’ll then see your new tax bill around October. There’s a basic equation to understanding it: tax rate x taxable value = tax bill. That total is what you’ll end up paying. Let’s use my 2021 bill as an example.

Last year, we paid $7,078.09 in property taxes on our house, about half of which was collected by Austin ISD. The Austin school board last year lowered the tax rate to its lowest level in twenty years—just a smidge more than $1 per $100 valuation. That’s in part because of controversial legislation passed by the Legislature in 2019. One provision limits cities and counties to no more than a 3.5 percent increase in total property tax revenue over the previous year, without voter approval. Another essentially forces school districts to ratchet down their tax rates when property values increase beyond a 2.5 percent threshold. Though these restrictions are expected to squeeze local governments and schools, they will have the effect of significantly buffering tax increases. “Just because appraised values go up does not mean that [property owners’] taxes are going to go up,” said Crigler.

Nonetheless, last year we actually paid more in school property taxes despite the lower rate, thanks to the increase in our home value. That could happen again this year in many parts of Texas. It’s soaring home values that are driving our rising property tax bills. Remember that 10 percent homestead cap that limits the growth in your home’s taxable value? Many of us could bump up against that cap year after year. At 10 percent annual growth, a home’s property tax bill will still nearly double in about seven years.

Who is responsible for this mess? Californians?

Glad you asked. It’s true, Texas has some of the highest property taxes in the nation, even though we are a low-service state.

Many folks direct their anger at their appraisal district, but that’s misguided. The appraisal district is largely just a technocratic middleman. The appraisers didn’t create the property tax system, nor are they responsible for the red-hot housing market in many of Texas’s cities and suburbs. It’s also easy to get mad at the local taxing entities—your school districts and cities and counties—but they did not design Texas’s system of funding government and are increasingly faced with unfunded mandates from the state. For the most part, taxing entities have been lowering their tax rates year after year. Finally, it’s a Texas pastime to blame Californians for the rising cost of housing here, but there’s not much evidence that new residents are the problem.

The fundamental reason that property taxes are so high is that Texas does not have a state income tax; it’s one of only seven states in the nation without one. Instead, we pay for government through two main sources of revenue: sales tax and property tax. “Most states rely on that three-legged stool of income tax, property tax, and sales tax,” pointed out Chandra Villanueva, a policy analyst with the left-leaning nonprofit Every Texan. “When you’re on a two-legged stool, it’s not very stable.”

A well-designed, progressive income tax could actually lower most Texans’ overall tax burden by decreasing how much low- and middle-income homeowners pay in property taxes while generating additional revenue by taxing the income of the wealthiest. But an income tax ain’t gonna happen in the foreseeable future—it’s about as politically popular at the Capitol as banning barbecue.

Okay, got it. We’re stuck with our reliance on property taxes. But that still doesn’t explain why they aren’t doing more to lower my taxes.

Believe it or not, both local and state governments have taken all sorts of action to provide “relief” from property taxes. The reality is that almost every measure—whether it’s more generous homestead exemptions or the state essentially forcing local governments to cut tax rates—is about just slowing the rate of growth rather than reducing tax bills. Past efforts at the Legislature to provide “relief,” in 2007 and 2015 and 2019, were hardly noticed by taxpayers.

Lawmakers know they can’t lower property taxes without seriously damaging the state’s already bare-bones public sector—public schools in particular. Property taxes are the main source of funding for public education in Texas. Either you have high property taxes or you have impoverished schools. The only way to cut the Gordian knot is to find new sources of revenue.

Then why don’t they find another source of revenue?

Much easier said than done.

Purists want to abolish property taxes altogether, somehow replacing the state’s main source of revenue with . . . something else, usually sales tax and the magic elixir of a booming economy. Long a fringe proposal, the notion of scrapping property taxes has become somewhat more mainstream in recent year. In 2019, while debating the twin issues of school finance and property taxes, many top Republican lawmakers—Governor Greg Abbott included—floated the idea of raising the state sales tax to a rate that would match California’s, the highest in the nation. The idea proved toxic even for many Capitol conservatives. In 2022, failed gubernatorial candidate Don Huffines ran in part on a platform of abolishing property taxes—while maintaining current levels of government spending.

These proposals never really go anywhere because the math doesn’t work, and opponents could credibly accuse the architects of raising taxes on lots of folks. Yet that doesn’t mean the dream will die. Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick has instructed a group of senators to study the possibility of eliminating the “maintenance and operations” tax, the biggest portion of the school property tax, ahead of the 2023 legislative session.

There are more economically viable options. One idea: close loopholes by, for example, extending the sales tax to services. “Our sales tax is very much a consumption-based tax, but we’re moving into a service-based economy and a lot of services are not taxed at all,” said Villanueva. Another idea: make the property tax system more equitable by forcing corporations to play by the same rules as homeowners. At present, businesses enjoy immense advantages in how their properties are appraised and taxed, starting with the perverse Texas law that allows nonresidential property owners to keep their real estate transactions a secret. The result is billions siphoned from Texas schools every year.

Democratic gubernatorial candidate Beto O’Rourke has pledged to level the playing field between homeowners and businesses and force sales-price disclosure, in addition to legalizing and taxing marijuana and expanding Medicaid to relieve overburdened hospitals.

Governor Abbott has countered with a “taxpayer bill of rights” that includes residential appraisal reform and setting a higher bar for local governments to issue debt. Leaders in the Texas House and Senate are also eager to use $3 billion in COVID-19 stimulus money to buy down property taxes, but the matter is tied up in court.

Phew, this is a lot. Anything else I need to know before I pour myself a drink?

You haven’t already?

I’ll leave you with a parting thought. Annual “sticker shock” from those appraisal notices is inducing political tremors centered on housing affordability. Homeowners and renters alike are worried about hanging onto their places in the face of a frenzied real estate market that shows no signs of abating. The pressure to “do something” about high property taxes is only growing. But property taxes are how we pay for police, firefighters, libraries, and public education. Even in a red state like Texas, most voters expect a basic level of services and a decent school system. If you mess with property taxes, you potentially mess with sacred cows. The problem is particularly acute when talking about school property taxes because the byzantine school finance system is intimately tied up with the complex property tax system. And many public education advocates are already worried about the way the state keeps forcing school districts to cut taxes without a dedicated revenue source to make up the difference.

“We’re really sort of marching into a disaster on how we fund our schools if we don’t look at an alternative revenue source,” said Villanueva. “And I think that’s what’s missing from this equation is people want good schools, they want public services, but then they get that sticker shock of their property tax bill without fully understanding the revenue system of the state and what we’re dealing with.”

So anyone who says there is an easy answer is most likely a demagogue or hasn’t studied the issue carefully enough. Bringing meaningful change—and not just cursory “relief”—will require political courage, creativity, and the engagement of an informed populace. Time for that drink!