This story was originally reported by Barbara Rodriguez of The 19th. Meet Barbara and read more of her reporting on gender, politics and policy.

Federal officials earlier this month announced a new initiative that they say will better ensure the safety and nutrition of baby formula in America, a directive that puts a spotlight on the current state of formula production and oversight — and may raise questions for some parents about which products they should buy to feed their young children.

“Operation Stork Speed” makes several commitments, including to review the nutrients in baby formula and to increase ingredient testing for heavy metals and other contaminants, according to a joint statement by the Department of Health and Human Services and the Food and Drug Administration, which reports to HHS.

The effort will be led in part by HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a former independent presidential candidate who gained popularity by promising to “Make America Healthy Again.” It’s a catch-all phrase closely aligned with President Donald Trump’s messaging that implies support for health and food regulations but has a throughline of distrust for the government entities tasked with that oversight.

Against that backdrop, parents may have questions about what this initiative will mean for what’s on store shelves right now and in the future.

“Is this good or bad for parents?” asked Dr. Steven Abrams, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Texas at Austin and a neonatologist who has written extensively about infant formula. “The answer is, it’s always good. Infant formula has always needed regular and frequent review.”

The federal government already heavily regulates infant formula to ensure its safety for consumers. The oversight has been dictated by a decades-old law that has also been periodically updated. As a result, the FDA has a system for conducting sanitary controls, “nutritional adequacy,” packaging and labeling of current infant formula products.

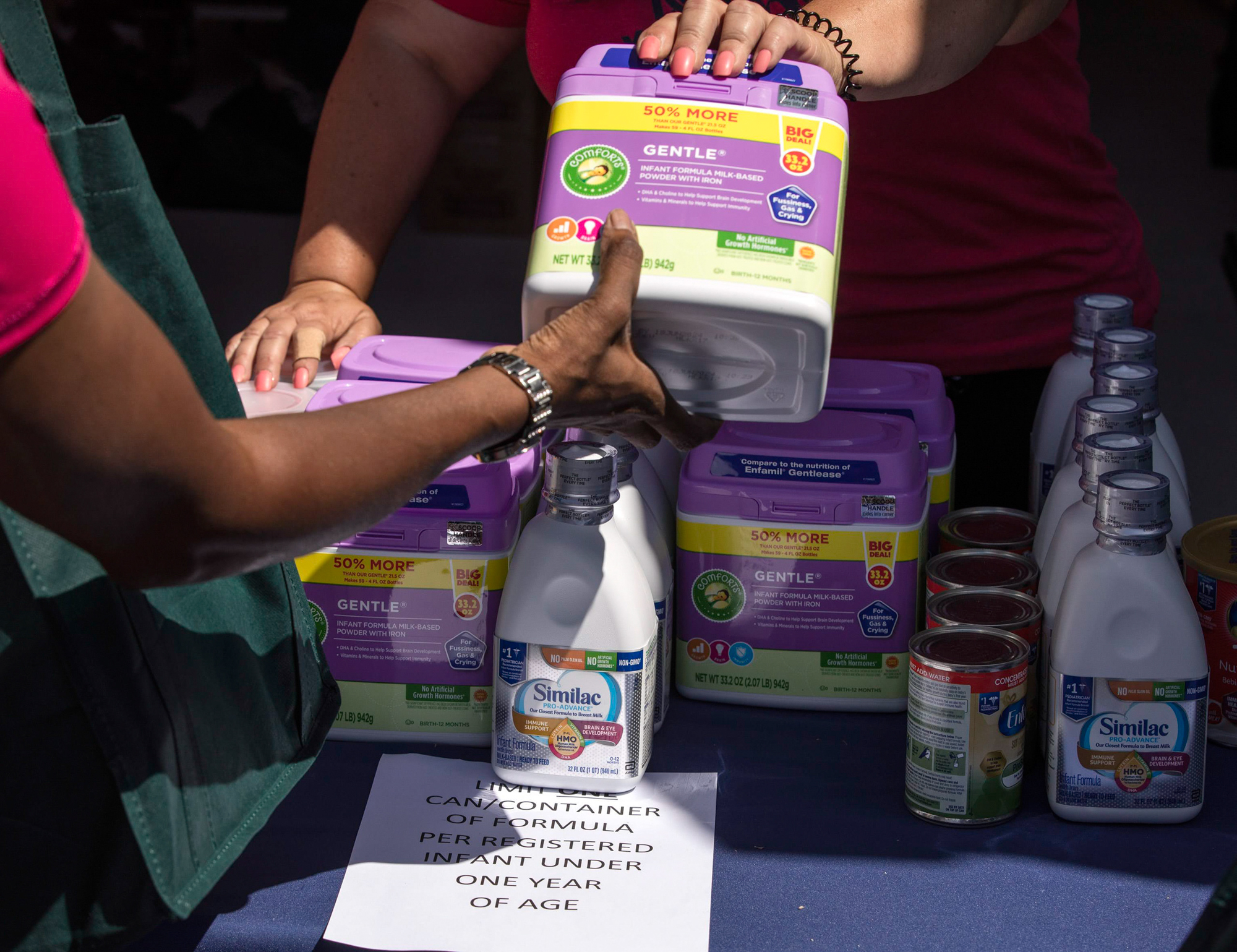

Still, advocates and public health officials say there is room for improvement, especially after an infant formula shortage in 2022 that was triggered in part by a key infant formula production facility in Michigan temporarily closing because of bacterial contamination. That greatly disrupted access to baby formula in America at a time of heightened supply chain issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Kennedy’s efforts will come in the midst of ongoing work by the federal government to improve infant formula access, including its safety. Abbott Nutrition, which ran the facility where the contamination happened and is one of the biggest makers of infant formula, issued a voluntary recall of several powdered formula products at the time. Months later, the FDA estimated that as many as nine children had died since early 2021 from consuming baby formula produced at the site — though the department could not directly link the infections because of limitations to its testing.

The shortage spotlighted how just a handful of companies manufacture the bulk of infant formula in the country, a dynamic that continues today.

Former President Joe Biden’s administration responded at the time with new oversight efforts, a short-term expansion of imported baby formula and an examination of the ongoing challenges in America’s baby formula supply, market competition and regulation. He signed into law legislation to increase that competition and, importantly, deemed infant formula “a critical food,” essentially increasing safety rules.

In January, ahead of Trump’s inauguration, the FDA released a long-term strategy to increase the “resiliency” of the U.S. infant formula market. Among the goals was preventing contamination through more robust food safety inspections and communicating more effectively with infant formula manufacturers on compliance and risk management practices.

But since returning to office, Trump has ordered massive cuts to the size of the government workforce, including at the FDA; some have been rehired. This month, most employees at Kennedy’s HHS department were offered voluntary buyouts, though the department later said some inspection roles were exempt.

It’s amid those realities that Kennedy — who has also been scrutinized for his anti-vaccine skepticism and spreading of medical misinformation — is promising to strengthen the access and safety of infant formula, which can be the sole source of nutrition for many children between birth and 12 months old. While most children start out receiving some breast milk, that dwindles as the child ages. Some public health experts believe it’s partly because of a government infrastructure that doesn’t do enough to support nursing parents while promoting infant formula.

“The FDA will use all resources and authorities at its disposal to make sure infant formula products are safe and wholesome for the families and children who rely on them,” Kennedy said in the statement issued hours after he met with the top manufacturers.

Kennedy appears to be directing some attention toward the nutrients in infant formula. The FDA currently requires that 30 nutrients be included — a list that is occasionally updated.

“It’s important to note that for babies who are not being breastfed, formula is a sole resource, so it can’t miss anything,” said Abrams, who has proposed some changes to the nutrient requirements to better reflect evolving research and consider rules around feeding premature babies.

It’s unclear for now what the scope of Kennedy’s ideas might be on nutrient changes. Last year, he highlighted research by activists that showed instances of toxic metals in some products. The role of toxins in foods, including children’s food, has already been the subject of renewed attention, including in the halls of Congress, and the FDA had also been examining the issue.

Consumer Reports published an investigation this month, the same day as the Operation Stork Speed announcement, that found traces of toxic chemicals in some infant formula. The nonprofit research and advocacy organization concluded that of the 41 types of powdered formula that its researchers tested for a number of toxic chemicals — including arsenic, lead, BPA, acrylamide and so-called “forever chemicals” known as PFAS — about half of the samples contained “potentially harmful levels” of at least one contaminant.

But the other half of tested formulas showed low or no levels of these chemicals, said Sana Mujahid, manager of food safety research and testing for Consumer Reports, which is now petitioning Kennedy to maintain staffing that ensures proper food safety. She also noted that environmental pollutants are pervasive in the food supply and some of the contaminants have been detected in breast milk, food and water. The report offers tips for parents on how to review the available products on the market.

“We really want these results to be empowering for consumers,” she told The 19th. “There are a lot of choices within the list, and we want parents to keep these results in perspective.”

Several public health officials who spoke with The 19th emphasized that if parents are concerned about the current quality of their baby’s infant formula, they should reach out to their pediatrician for guidance about product selection. They should use clean water when using powdered formula. And they should not make their own infant formula, which can lack key nutrients for babies.

While the Biden administration spent several years addressing key supply chain aspects of infant formula access, stakeholders such as Laura Modi say now there’s a window to permanently make the system better. Modi is the CEO and co-founder of Bobbie, an infant formula company that launched in 2021 and has expanded its production in the past several years.

When Kennedy met with infant formula manufacturers ahead of the announcement, Modi was in the room — the only mother, she noted.

“The beautiful shift that I am seeing now is that we are moving away from, ‘How do we address a crisis?’ to ‘How do we put in a long-term solution?’” she said.

Still, some advocacy groups that monitor food safety question the execution amid reports of job cuts at the FDA and other departments that oversee food quality. In mid-February, the top food safety official within the FDA resigned in response to the cuts. At the Agriculture Department, which is a separate department but is intertwined with government oversight of food, officials disbanded a key committee that studies deadly bacteria and was examining pathogens that can turn up in infant formula.

“They test products and they ensure safety and they do inspections,” said Jill Rosenthal, director of Public Health Policy at the Center for American Progress, a group that has advocated for removing toxins in foods. “Cutting their capacity is certainly not going in the right direction if we want to make sure that formula is safe.”

That could extend to independent oversight. An audit of the FDA’s response to the Michigan plant closing was released last year by the Office of Inspector General that oversees HHS. The report found the FDA “had inadequate policies and procedures or lacked policies and procedures to identify risks to infant formula and respond effectively through its complaint, inspection, and recall processes.”

The inspector general listed on the report, Christi A. Grimm, was fired in January by Trump in a two-sentence letter that was part of a mass firing of inspectors general. Grimm and others are challenging the firings in court.

Abrams said any changes to the infant formula industry must also consider equity, since half of all infant formula sold in the United States is through the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children, also known as WIC, for low-income families. Manufacturers compete for that contract, and he wonders how any expansive changes could affect the cost of formula that reaches those families. Abrams said families enrolled in the WIC program should be among the stakeholders involved in any potential changes to the nutrition of infant formula — along with science-based, independent reviewers.

Abrams also said there is room for addressing the marketing practices of infant formula manufacturers in America. While they are required to have certain nutrients in their products, some make additional health claims that are not backed by science. Among Operation Stork Speed’s plans are labeling and ingredient transparency.

“That’s a longstanding issue, what I call the chaos in the formula aisle, the difficulty in families identifying what the best formulas might be for their babies,” he said.

Modi said her main takeaway from meeting with Kennedy and the other infant formula manufacturers was a commitment to quality, safety and supply. And she wants parents to know that.

“This is a very regulated product and market, which means the FDA, the government and the private sector really need to be working together to see those changes,” she said. “It’s not just one. If we just leave the private sector to do it, we’re not going to be able to advance the regulations. And if we advance the regulations without private sector support, we’re not going to see a change to formula and market. I think what we’re seeing is the importance of all of these things coexisting together.”