Sensory processing disorder (SPD) is a term that’s relatively new for educators. You may hear it while sitting in an IEP meeting listening to an occupational therapist explain a sensory processing evaluation, when a parent explains that their child disrupted your lesson because they were dysregulated, or when a student insists they need a fidget to help them focus.

As conditions go, sensory processing disorder is new, and it’s controversial. Here’s everything you need to know the next time someone mentions SPD.

What is sensory processing disorder?

First, we all process sensory information all the time. Right now, the brightness of the screen you’re reading on, any flickering lights, maybe birds singing outside, are all sensations that your brain has to either pay attention to or ignore and filter out.

The idea of sensory integration was first identified by occupational therapist A. Jean Ayers, PhD, in the 1970s. Ayers hypothesized that that our sensory systems develop over time, like other aspects of development, and that deficits can occur along the way. According to Ayers, sensory processing deficits occur when sensory neurons are not functioning, which leads to deficits in development or emotional regulation. The idea behind SPD is that, for some people, the sensory information around them is either too much or not enough.

What does sensory processing disorder look like?

Each child who has deficits with sensory functioning will present differently, but there are some themes:

- Big reactions to sensory input: Kids may have a strong reaction to loud noises, covering their ears or trying to avoid loud places.

- Getting easily overstimulated: They may be overstimulated in environments that don’t bother other people. For example, a walk through Target might be a good experience for you, but the lights and smells might be completely overwhelming for a child who has sensory processing concerns.

- Strong sensory preferences: A child with SPD may prefer a certain type of touch, like very deep pressure.

Image: ASD Helping Hands

We all manage sensory input differently; the most important consideration is whether or not the child’s sensory processing impacts their daily life. For example, a child may have a strong reaction to loud noises. If they are in a classroom that is typically quiet and have warning before a loud noise happens, their sensory processing deficit may not have a great impact on their day. On the other hand, the same child in a loud classroom or at a fireworks display may have a meltdown.

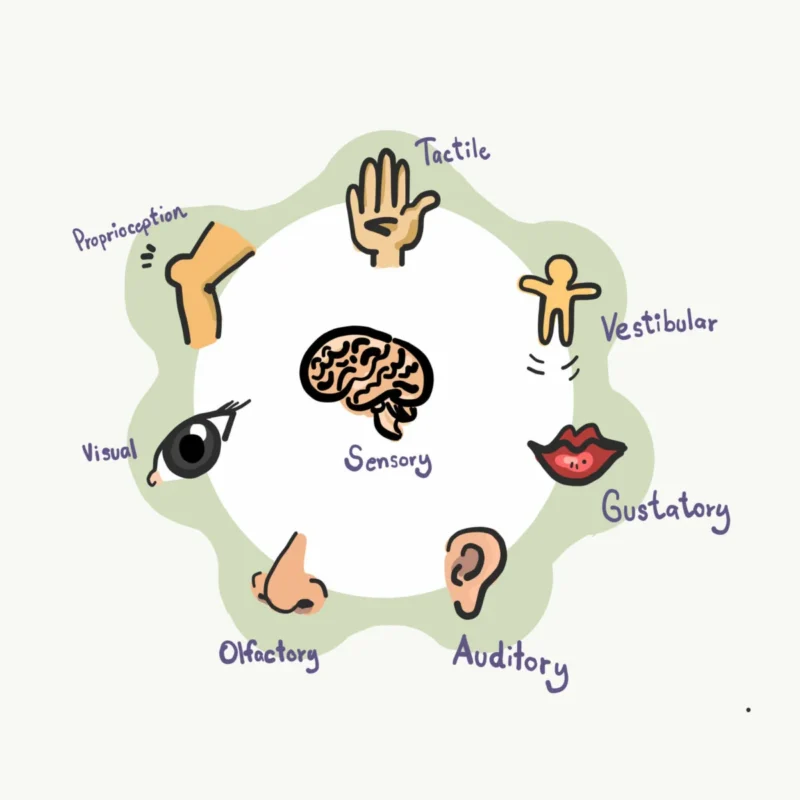

Which senses are involved?

When we talk about SPD, we’re talking about input we get from the five senses: taste, vision, hearing, touch, smell. We’re also talking about two internal senses: proprioceptive (body awareness) and vestibular (movement).

Image: Growing Early Minds

Proprioceptive receptors are in joints and ligaments and give feedback about motor control and posture. Our proprioceptive system gives our brains information about where our body is and how to move. Children who are under-sensitive may love jumping and crashing. While children who are over-sensitive don’t know where their body is in comparison to others and may appear clumsy.

Vestibular receptors are in the inner ear and tell the brain where the body is in space. This influences balance and coordination. Kids who are under-sensitive are in constant motion; kids who are over-sensitive may be afraid to do things that require balance, like climbing or standing on one foot.

What are symptoms of SPD?

Kids with typical sensory processing can filter out a lot of stimuli—the buzzing of the air conditioner, the noise from the hallway outside, the smell of the teacher’s coffee, that one flickering fluorescent light. Kids with SPD either have a hard time filtering, or the stimuli are dulled and their world feels muted, leaving them seeking sensory input.

Some things that can trigger big reactions in kids with SPD:

- Hair brushing

- Tight clothes

- Loud noises

- Bright lights (sunshine, strobes)

- Sticky fingers or touching certain substances (kinetic sand, etc.)

- Tags on clothes

- Strong scents (detergent, perfume)

How are kids diagnosed?

Sensory processing disorder is not an official diagnosis in either the DSM-IV or the American Academy of Pediatrics. An occupational therapist is typically the provider who will investigate sensory processing and bring up SPD, either as part of a larger diagnosis (like autism or ADHD) or on its own.

Kids who have trouble with sensory processing are often identified during their toddler years, when parents or caregivers notice concerning behaviors, like:

- Screaming if something touches them—like screaming if their hands get sticky or if their face gets wet

- Throwing a tantrum when they have to put on clothes

- Having a high or low pain threshold

- Crashing into walls or people

- Pushing up against people

- Putting objects, like paint or rocks, into their mouth

- Running away without regard to safety

- Temper tantrums that come out of nowhere and take a while to resolve

If a parent or teacher raises concerns that a child has sensory processing issues, an occupational therapist will review a sensory processing measure (a checklist) and conduct an evaluation to determine whether and how a child’s sensory processing is impacting them on a daily basis.

Is SPD just ADHD or autism?

Not quite. A child with ADHD or an autistic child, may have sensory processing issues, but a child with sensory processing issues does not automatically have ADHD or autism.

Read more at ChildMind.org.

Is SPD real?

There is debate about whether or not SPD is real. Occupational therapists argue that it is, while pediatricians and psychologists may disagree. Some doctors argue that what is being labeled as SPD is actually ADHD, anxiety, or autism.

SPD is not included in the conditions in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) that doctors use for diagnosis. And the American Academy of Pediatrics stated that it is “unclear” whether children who present with sensory problems have a disorder or if their sensory considerations are associated with another developmental delay, like autism or ADHD.

However, research is just starting to be done on SPD. One study found a difference in the brains of children with sensory processing disorders. In the study, researchers looked at the white matter in the brains of 16 8–11-year-old boys and 24 controls. The imaging found significant differences in the brains of the children with sensory processing problems, primarily in the white matter.

Read more about The Debate Over Sensory Processing.

How many kids have SPD?

Studies estimate that 5% to 16.5% of the general population have symptoms associated with SPD, though those estimates are higher among autistic individuals and those with ADHD.

What causes SPD?

As with other developmental delays, the causes of SPD are unclear and may relate to genetics. There are some factors that can put a child at risk for SPD, including premature birth, malnutrition, and extreme deprivation during the early years (infrequent handling, frequent bundling).

How is SPD treated?

Source: Harkla.co (sensory brush)

Typically, occupational therapists work with kids with SPD using sensory-based therapies, activities that are believed to provide sensory inputs to help organize the brain’s sensory system. A child who needs support with sensory processing may be given a sensory diet, or activities throughout the day to give them the sensory input their system is seeking. Some things that can be included in a sensory diet:

- A brushing protocol

- Swinging

- Animal walks (bear walks, Froggie jumps)

- Wheelbarrow walks

- Trampoline jumps

- Deep-pressure squishing with pillows or balls

- Wearing a heavy backpack or weighted vest

- Playing with play dough or kinetic sand

- Chew toys or chewy foods

- White noise or a favorite music

Shot of a smiling girl enjoying a sensory therapy on a swing with her physiotherapist assisting her

Image: Friendship Circle

Treatment can also include lifestyle changes, like clothing without tags, headphones, or sunglasses.

In addition to a sensory diet, occupational therapists provide a sensory integration (SI) approach that begins in a controlled environment to challenge the sense without overwhelming them. Over time, the goal is to help the person learn to manage sensory input so that it doesn’t impact their everyday functioning. This can take a long time; the idea is that by providing the sensory integration, it changes how the brain processes sensory input, which can take years.

Read more about sensory diets at Kid Sense.

What about fidgets?

Source: Pexels.com

Fidgets, or sensory toys, can be used as part of a sensory diet. The idea is that sensory toys engage a child’s preferred sense. If a fidget is working, a child will be able to focus or stay calm in a stressful situation. Not all kids need fidgets, and fidgets work best when they are part of a larger plan (like an IEP or an occupational therapy plan) to help a child focus and manage throughout their day.

Read more: The Best Sensory Toys for All Ages

Do sensory diets, fidgets, and other treatments work?

Research on SPD, sensory diets, and other techniques is new. It’s not clear if the treatments actually work or if they are “evidence-based,” meaning that there is enough research done on the techniques to show that they are effective.

Recommended Reading

The Out-of-Sync Child by Carol Stock Kranowitz

Raising a Sensory Smart Child by Lindsey Biel and Nancy Peske

Do you have questions about sensory processing in the classroom? Connect with other teachers in the WeAreTeachers HELPLINE on Facebook.

For more articles about trends in education, be sure to subscribe to our newsletters.