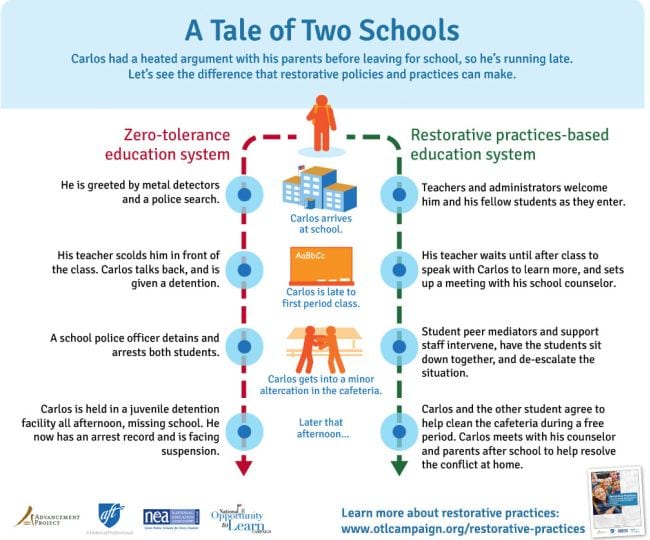

Most schools use punitive discipline systems: Break a rule and you’re punished with detention or even suspension. But these systems can interrupt a student’s education and lead to further bad behavior. They also don’t provide kids with any skills for working through issues with others. That’s why some schools are trying restorative justice instead. Here’s what you need to know about it.

What is restorative justice in schools?

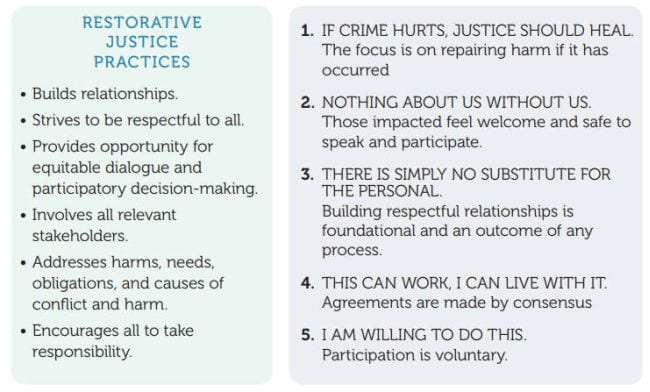

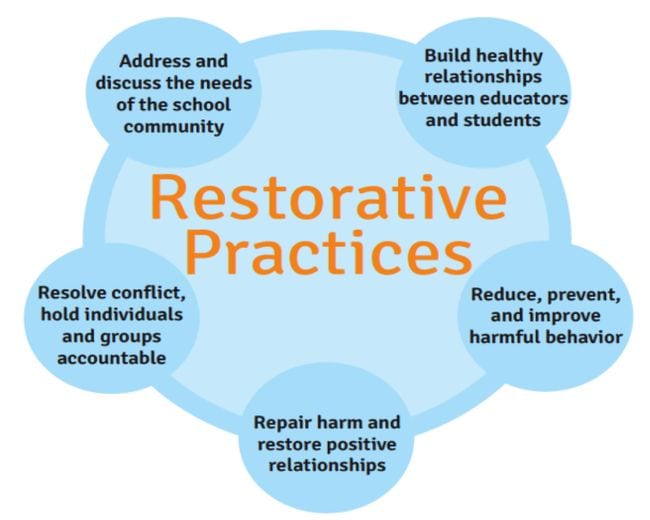

Restorative justice is a theory of justice that focuses on mediation and agreement rather than punishment. Offenders must accept responsibility for harm and make restitution with victims. Indigenous people like the Maori have used this system successfully in their communities for generations.

In recent years, various countries have tried the practice in an effort to make their criminal justice systems more effective. This led to the exploration of restorative justice in schools, especially those with high rates of student misbehavior.

In California, Oakland Unified School District began using the program at a failing middle school in 2006. Within three years, the pilot school saw an 87% decrease in suspensions, with a corresponding decrease in violence. The practice was so successful that by 2011 OUSD made restorative justice the new model for handling disciplinary problems.

What are the basic practices of restorative justice?

“Restorative justice is a fundamental change in how you respond to rule violations and misbehavior,” said Ron Claassen, an expert and pioneer in the field. “The typical response to bad behavior is punishment. Restorative justice resolves disciplinary problems in a cooperative and constructive way.” Schools like OUSD use a three-tiered approach focused on prevention, intervention, and reintegration.

Restorative Justice Tier I: Prevention

The first tier is all about community-building as a preventive measure. Teachers or peer facilitators lead students in circles of sharing, where kids open up about their fears and goals. “The circles are based on indigenous practices that value inclusiveness, respect, dealing with things as a community, and supporting healing,” explains David Yurem, OUSD’s first program manager. “Kids really resonate with this process. I’ve seen kids share things that I was extremely surprised by, like eighth grade boys talking about what scares them. To seem weak in their world is a life-threatening thing, so I was really impressed.”

Students play an integral part in creating the climate of Tier I. The teacher and students start the year by creating a classroom respect agreement. Everyone agrees to be held accountable. The contract is an extremely effective way of maintaining harmony in the classroom. “Teachers can’t say, ‘Here are my rules, sign them,’” says Yurem. “That doesn’t work. There’s no ownership for the students in that. If the children help create the rules, then they have ownership. And if they break them, they can be referred back to them.”

Restorative Justice Tier II: Intervention

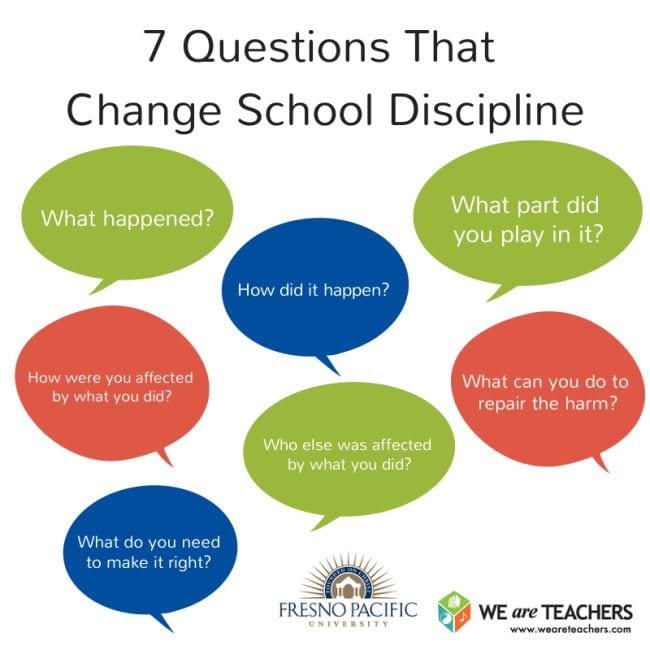

Tier II comes into play when students break rules and someone has caused harm to someone else. In traditional justice, this is when punishments are meted out. Restorative justice instead turns to mediation. The offending student is given the chance to come forward and make things right. They meet with the affected parties and a mediator, usually a teacher.

The mediator asks nonjudgmental, restorative questions like What happened? How did it happen? or What can we do to make it right? Through their discussions, everyone learns about what happened, why it happened, and how the damage can be fixed. “They’ll talk about what can be done to repair the harm,” Yurem shares. “They’ll come up with a plan and fulfill that plan. And hopefully, the relationship will be stronger. It’s really all about relationships—building and repairing them.”

Restorative Justice Tier III: Reintegration

Tier III aims to help kids who’ve been out of school due to suspension, expulsion, incarceration, or truancy. Returning to school life can be a real challenge in those cases. Many students in traditional environments quickly re-offend or drop out again. Restorative-justice practices seek to reduce this recidivism by providing a “wraparound” supportive environment from the start. They acknowledge the student’s challenges while promoting accountability and achievement.

Does restorative justice really work in a classroom?

So what does all this look like in a real-world school or classroom? Roxanne Claassen was one of the first teachers to try restorative justice in school. She’d seen the success her husband, Ron, had using it in his work with the juvenile criminal justice system. Roxanne decided to try the model in her Fresno, California, elementary school classroom.

Claassen worked with students to write a respect agreement. Together they determined how they would treat each other to create a positive classroom community. If a student violated the agreement, Roxanne reminded them of it and asked if they wanted to honor it. Ninety percent of the time, the student did, and the problem ended there.

If the problem continued, Claassen worked together with the student to try to find a solution. “You say, ‘Here’s the problem. What can we do to fix it?’ The message you’re sending the child is, ‘I’m not against you, I’m for you. I want you to succeed,’” emphasizes Claassen.

A Real-Life Example

In one instance, two of Claassen’s eighth grade boys broke a paper towel dispenser in the bathroom. At first, no one admitted responsibility. Claassen told them, “We have a restorative discipline system here, so we accept responsibility and can make things as right as possible. But we can’t do that unless someone accepts responsibility.”

The boys admitted they’d done it. Claassen called a meeting with all the people involved or affected by the incident—the boys, their parents, and the custodian. They talked about what happened, and everyone had a voice. “In that process, the custodian had a chance to let the students know how difficult it is to replace a dispenser,” said Claassen. “It gave the students incredible knowledge of a real-world situation in a way a suspension never could, and relationships improved instead of being damaged.”

One of the students couldn’t afford to pay to replace the dispenser. So the student himself suggested that he could work with the custodian to pay his debt. He enjoyed it so much that he continued to help the custodian long after he’d finished his restitution!

Does restorative justice address racial justice?

OUSD’s Restorative and Racial Justice homepage is clear: “There is no restorative justice without racial justice.” To begin with, this means honoring the indigenous roots of the practice. It also means encouraging program participants to consider how racial privilege and prejudice affect them all.

The Center for Court Innovation runs restorative justice programs in five underserved Brooklyn schools. They’re trying to address the subject through a racial justice lens. “Restorative justice is about accountability and repairing harm,” they note. “What about accountability for the system that has produced these underserved and essentially segregated schools and then punishes the kids for reacting to that neglect?”

In other words, schools must address racist policies and practices along with restorative justice efforts. They can use the system to help historically privileged students make amends to the victims of long-standing prejudices. This is an extremely tricky topic and a fairly new one. Try these resources to learn more:

What are the potential benefits of restorative justice?

If you’re thinking that this sounds like a lot of work, especially up front, you’re right. But many teachers and administrators who use these programs say the benefits far outweigh the effort.

Less stress

Teachers who use restorative discipline practices find that behavior in their classrooms improves dramatically. They have better relationships with their students and, therefore, less stress from unresolved conflicts. “Restorative discipline improved my relationships with students,” states Claassen. “Instead of making the relationships more difficult, it brought us together and improved our interactions.”

More time for teaching

“You spend less time … on discipline and have more time available for teaching and interaction when you use restorative practices,” Claassen observes. “Students aren’t afraid to admit when they’ve done something wrong as they are in a punitive environment, so you save a lot of time investigating who did what.”

Ron adds, “When you have a punitive system, the automatic response is to deny responsibility because you know you’ll get punished. With a restorative justice system, the incentive is to admit what you did because you know there’s going to be a restorative process to make things right.”

Better outcomes for students

Statistics show that using restorative practices keeps kids in school. Punitive systems often remove students from the classroom, even for minor offenses. With restorative justice, everyone works together to keep kids in the classroom where they can learn. Children who are expelled often end up in what education reform activists call the school-to-prison pipeline. Restorative justice tries to stop this cycle and keep kids on track with their education.

Addressing root causes

Restorative justice encourages kids to explore the reasons and effects of their offenses. “Restorative justice addresses the harm caused by the offense and the harm revealed by the offense,” says Yurem. “When you get these kids talking, you learn about the traumas they have faced. Maybe their brother was killed, or their father was sent to prison. If you can get to the root of the cause of the offense, you’re truly stopping the cycle.”

Real-life skills

Even if there isn’t a major underlying problem, talking about an issue is an important skill for students to learn. “The restorative process teaches students how to resolve conflict in a positive way,” Ron Claassen says. “It helps them develop rational skills—to understand a situation, follow a process, and resolve it. These are life skills they can take with them into the world.”

What are the drawbacks of restorative justice in schools?

For restorative justice to work, it requires engagement from all involved parties. If the offender isn’t willing to take responsibility and make meaningful restitution, the program can’t help. Schools using this system find they still need traditional disciplinary actions available for circumstances like this.

More than this, restorative justice in schools requires a pledge of time and money from the district and its administration. There are multiple examples of schools that set aside funds to implement the program but leave the money unspent. Other districts encourage teachers to use restorative discipline but provide little or no training or support. And busy teachers are understandably leery of trying yet another program that’s supposed to solve all their problems.

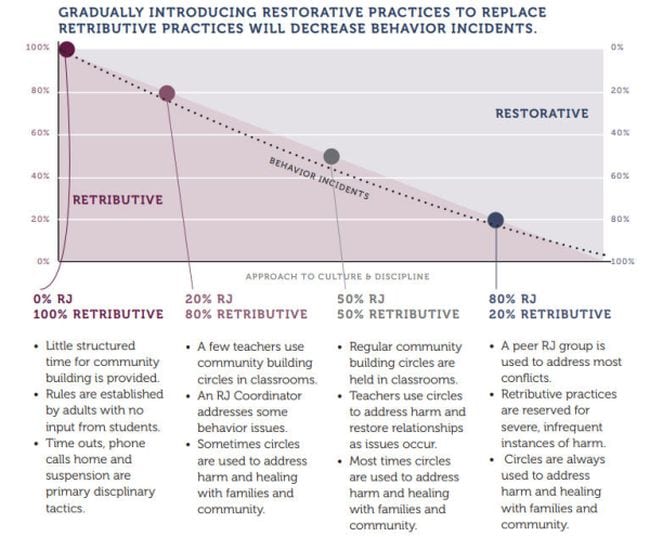

Schools that dedicate themselves fully to the system, like Oakland USD and Chicago Public Schools, see real change and benefits. But the time, money, and enthusiasm required to make it work can be prohibitive for others.

What do real educators think about restorative justice in schools?

When this topic pops up for debate in our We Are Teachers HELPLINE and Principal Life Facebook groups, educators tend to have a lot of opinions about it. Here are some of their thoughts:

- “We started RJ this year, and since it was so new there was a STEEP learning curve for everyone involved, despite numerous trainings. Just remember that some students will respond to it right off the bat, some take time, and others are just not going to participate in circles and things, and that’s OK. My opinion is this: In theory, RJ is an excellent idea. I really think it can help build student-teacher relationships. In practice, the school must go ‘“’all in’ in order for it to work.”

- “I love this approach. It has been highly successful for me and my colleagues who took it seriously. I have seen improvements at tough schools that I’ve worked in. … By the way, this isn’t just for minority children. It isn’t just for Caucasian teachers. It’s for all people. These practices can also resolve issues with teacher and admin, parents and schools, etc.”

- “I find that many kids don’t open up in the circle and are afraid to share because the other kids don’t always respect what is said there. Not sure how to change that, but because they aren’t genuine in the circle, they are not reaping the benefits of genuine communication.”

- “Restorative justice cannot be rushed. It does not work when those participating have a time limit of 20 minutes and back to class.”

- “It takes time to build the culture. Have someone come in and give an overview of the philosophy and to share a circle. This gets everyone thinking. Don’t demand that everyone must do it … but request that everyone begins building relationships with their students and colleagues. Start with a team of teacher leaders who practice it and share their experience and celebrations. It will catch on! It takes about 3 years to build the culture!”

How can schools implement restorative justice?

On their own, teachers can use some aspects of the restorative justice system in their classrooms. “Respect agreements” are a good place to start, giving students a stake in making the classroom successful. Then, spend some time learning about sharing circles and mediation (see resources below).

School-wide or system-wide restorative justice takes the full commitment of everyone involved in the education process—teachers, administrators, students, and parents. Schools can spend months or even years fully rolling out a program. It’s not the right option for everyone, as it requires an extensive dedication of time and money. Teachers interested in bringing a program to their schools should work with their administrators to explore the process. Oakland USD offers a particularly useful Restorative Justice Whole-School Implementation Guide that provides a comprehensive look at what it takes to make it work.