Tiina Sanila-Aikio cannot remember a summer this warm. The months of midnight sun around Inari, in Finnish Lapland, have been hot and dry. Conifer needles on the branch tips are orange when they should be a deep green. The moss on the forest floor, usually swollen with water, has withered.

“I have spoken with many old reindeer herders who have never experienced the heat that we’ve had this summer. The sun keeps shining and it never rains,” says Sanila-Aikio, former president of the Finnish Sami parliament.

The boreal forests here in the Sami homeland take so long to grow that even small, stunted trees are often hundreds of years old. It is part of the Taiga — meaning “land of the little sticks” in Russian — that stretches around the far northern hemisphere through Siberia, Scandinavia, Alaska, and Canada.

It is these forests that helped underpin the credibility of the most ambitious carbon-neutrality target in the developed world: Finland’s commitment to be carbon neutral by 2035.

The law, which came into force two years ago, means the country is aiming to reach the target 15 years earlier than many of its EU counterparts.

In a country of 5.6 million people with nearly 70 percent covered by forests and peatlands, many assumed the plan would not be a problem.

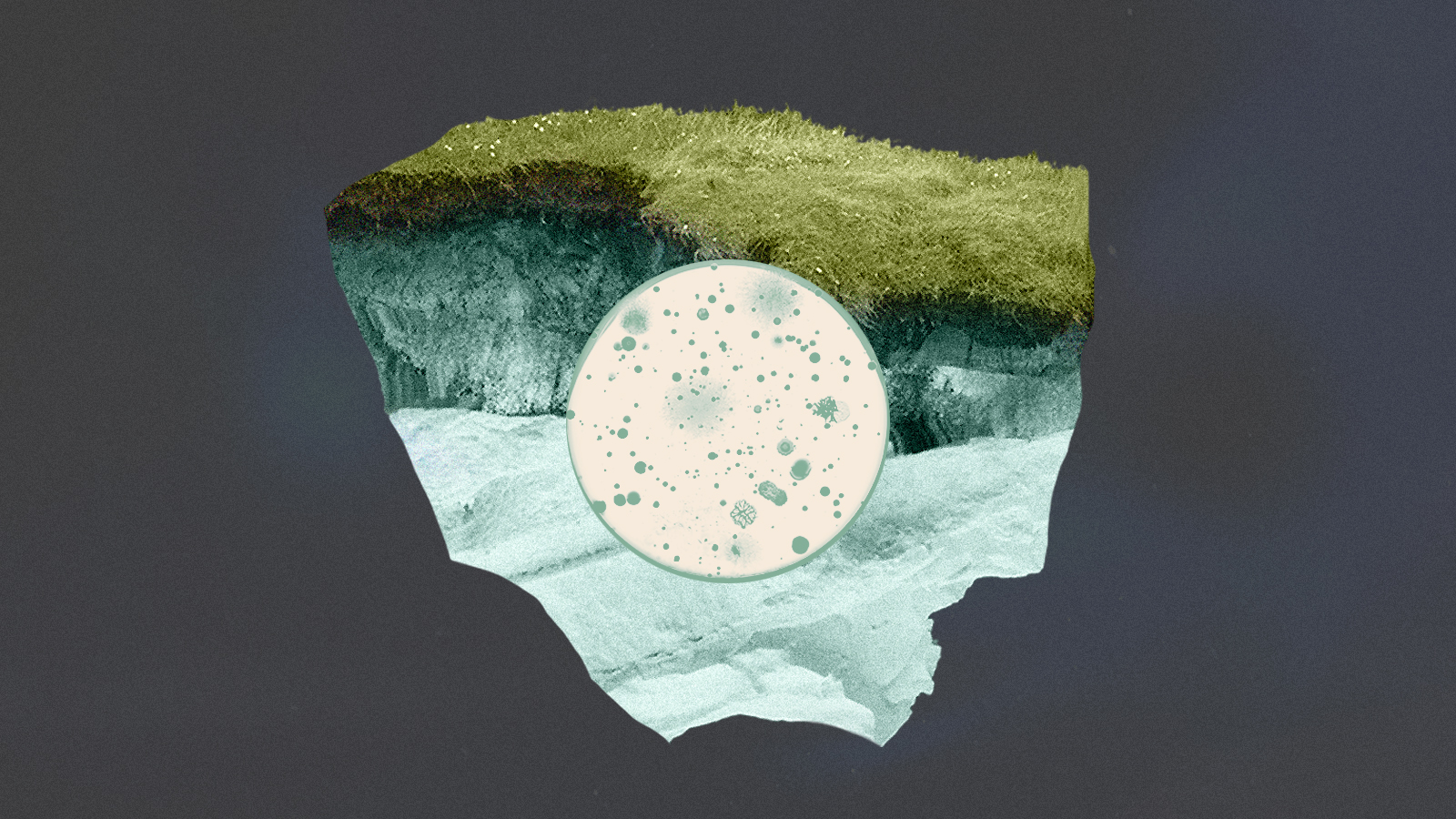

For decades, the country’s forests and peatlands had reliably removed more carbon from the atmosphere than they released. But from about 2010, the amount the land absorbed started to decline, slowly at first, then rapidly. By 2018, Finland’s land sink — the phrase scientists use to describe something that absorbs more carbon than it releases — had vanished.

Its forest sink has declined about 90 percent from 2009 to 2022, with the rest of the decline fueled by increased emissions from soil and peat. In 2021 and 2022, Finland’s land sector was a net contributor to global heating.

The impact on Finland’s overall climate progress is dramatic: Despite cutting emissions by 43 percent across all other sectors, its net emissions are at about the same level as the early 1990s. It is as if nothing has happened for 30 years.

The collapse has enormous implications, not only for Finland but internationally. At least 118 countries are relying on natural carbon sinks to meet climate targets. Now, through a combination of human destruction and the climate crisis itself, some are teetering and beginning to see declines in the amount of carbon that they take in.

“We cannot achieve carbon neutrality if the land sector is a source of emissions. They have to be sinks because all emissions can’t be decreased to zero in other sectors,” says Juha Mikola, a researcher for the Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke), which is responsible for producing the official government figures.

“When these targets were set we thought that land removals would be around 20 million to 25 million tons and we could reach the target. But now the situation has changed. The main reason is the forest land sink decreasing by almost 80 percent,” he adds.

Tarja Silfver, a research scientist at Luke, says: “It makes the targets really hard to achieve. Really, really hard.”

The reasons behind these changes are complicated and not fully understood, say researchers. Burning peatland for energy — more polluting than coal — remains common. Commercial logging of forests — including rare primeval ecosystems formed since the last ice age — has increased from an already relentless pace, making up the majority of emissions from Finland’s land sector. But there are also indications that the climate crisis has become a driver of the decline.

Rising temperatures in the most rapidly warming part of the planet are heating up Finland’s soils, increasing the rate at which peatlands break down and release greenhouse gases into the air. Palsas — enormous mounds of frozen peat — are rapidly disappearing in Lapland.

The number of dying trees also increased in recent years as forests are stressed by drought and high temperatures. In southeast Finland, the number of dying trees has risen rapidly, increasing 788 percent in just six years between 2017 and 2023, and the amount of standing deadwood — decaying trees — is up by about 900 percent.

The country’s forests, mostly planted after the end of the second world war, are also maturing, approaching the maximum amount of carbon that they can naturally store.

Bernt Nordman, from WWF Finland, says: “Five years ago, the general narrative was that the forests in Finland are a huge carbon sink — that actually they can offset emissions in Finland. This has changed very, very dramatically.”

These changes, while anticipated by climate scientists, are worrying policymakers. Finland is not alone in its experience of decline or vanishing land sinks. France, Germany, the Czech Republic, Sweden, and Estonia are among those that have seen significant declines in their land sinks.

Drought, climate-related outbreaks of bark beetle, wildfire, and tree mortality from extreme heat are ravaging Europe’s woodlands on top of pressure from forestry. Across the EU, the amount of carbon absorbed by its land each year fell by about a third between 2010 and 2022, according to the latest research, endangering the continent’s climate target.

Johan Rockström, of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, says: “The reasons [for Finland’s shift] are not fully explored but it’s very likely a combination of unsustainable forest management and also dieback because of droughts and extreme weather conditions. We see similar trends in Canada, very much from disease outbreaks, but also in Sweden.

“These are countries in the temperate north that have factored in their carbon sink as a very central part of their climate policy,” he says. “It’s such a big risk for these governments.”

In Salla, southern Lapland, Matti Liimatainen and Tuuli Hakulinen walk through the remnants of a rare primeval forest. Black lichen hangs from the branches above enormous, waist-high ant nests. On either side of the muddy track, dead grey trees stand in a sea of green — an indication, the forest campaigners say, that this area has never been disturbed by humans before.

But the road they are on is freshly cleared: a forestry track to allow loggers in. Behind them lies a barren, clear-cut tract of land, studded by stumps and bare earth. Soon, the surviving trees will be turned into pulp.

Liimatainen, a Greenpeace forest campaigner, and Hakulinen, project manager with the Finnish Association for Nature Conservation, have traveled to the remote forest to document rare species that live there, part of a cat-and-mouse game with the forestry industry. By establishing the presence of endangered wildlife, they hope to prevent the mills getting sustainable timber certification and grant the forest a stay of execution.

“This was part of a massive old-growth forest and it was cut down last winter,” says Liimatainen, pointing to the clear-cut expanse.

A fraction of Finnish forest is believed to be untouched, often found on or around peatlands, but there is little formal protection from the government. New areas are regularly cleared for pulp and lumber.

Researchers say that slowing forest clearance, better protection for intact ecosystems, and improved forest management could help to restore Finland’s land sink. But the cost has led to resistance from the forestry industry.

Finland’s finance ministry estimates that harvesting a third less would reduce GDP by 2.1 percent, costing between 1.7 billion and 5.8 billion euros (between $1.84 billion and $6.28 billion) a year. Increasing forest protection would also cost the country hundreds of millions of euros, according to the Finnish Nature Panel. The state owns 35 percent of forests, while private owners, companies, municipalities, and various organizations own the rest.

Finland’s leading timber companies say the country’s forests still absorb more carbon than they release, while acknowledging that the amount has shrunk dramatically in recent years. Fossil fuels, rather than forestry, represent the biggest threat to the climate, they say.

A spokesperson for Metsä Group, a cooperative of more than 90,000 forest owners, says that whenever forest is harvested, new trees are planted, which means carbon sequestration can be increased over the long term.

A spokesperson for UPM, a Finnish forestry firm, says the 2035 carbon-neutrality target is overly optimistic and “too many climate policy hopes were pinned on the land-use sector sinks”.

“The calls for restricting harvesting often miss the point that the state owns approximately a quarter of Finnish forests. The government can restrict harvesting in its own land if it is willing to bear the significant direct and indirect financial consequences,” they say.

Under the right-wing government that was elected last year, much less emphasis has been put on meeting climate targets. The Finnish government did not respond to The Guardian’s request for comment.

But researchers warn that rising global temperatures are likely to further degrade Finland’s land sink. Studies indicate that across boreal ecosystems, the forest is losing its ability to absorb and store as much carbon.

“There are some really serious scientific scenarios where, if climate change proceeds, the spruce in Finland will not survive, at least in southern Finland,” says Nordman. “The whole forestry system is based on this tree.”

For communities that have always lived in the Arctic Circle, the changes are already clear. As autumn approaches, Sanila-Aikio is preparing for the return of the reindeer from their summer feeding grounds ahead of an uncertain winter.

If the dry spell holds, there will not be mushrooms for the reindeer, she explains. “If they do not fatten up, they will starve,” she says.