Early Tuesday afternoon, Kurt Wilkening drove to his usual Election Day polling location at a church in Sarasota, Florida. But the 90-year-old quickly discovered no one there, the building destroyed by flooding during hurricanes Milton and Helene earlier this fall. So Wilkening hopped back into his car and headed to another location in Bird Key, the barrier island where he lives. When he arrived, he was told he was once again at the wrong spot, and directed to yet another. That site, a recreation center that doubles as a voting precinct and a Federal Emergency Management Agency disaster recovery center, finally ended up being his correct polling place.

“Why didn’t they put this in the paper?” he said, gesturing toward the polling station. Wilkening, whose home sustained “tremendous” flooding and damage during both storms, expressed frustration at the run-around. “It’s been a real challenge. When you are 90 years of age, it’s tough to deal with all this.”

It’s been less than two months since Hurricane Helene slammed into Florida’s western flank as a Category 4 storm before quickly pivoting north to unleash torrential rain and wind on five more states across the Southeast. The September storm killed nearly 230 people, displaced thousands more, and caused some $53 billion dollars in damage. Even as North Carolina, the state that bore the brunt of the storm’s impact, was still assessing the wreckage, Florida braced for another major hurricane in nearly the same corridor. Milton hit as a Category 3 on October 9, knocking out power for millions and killing more than 20 people in several counties.

It was the first time that two major hurricanes made landfall in the United States within weeks of a presidential election. Georgia and North Carolina, both still recovering from Helene, are two of seven swing states that will likely determine the outcome of the race.

In Florida, record-breaking storm surge inundated coastal polling locations, forcing their closure for Election Day. Inland, in states like North Carolina, the hurricane’s rain-driven flooding washed away homes and roads, closed mail routes, and destroyed voting sites. Election officials along the storms’ paths scrambled to ensure access to early voting and absentee ballots for hurricane victims and establish temporary poll locations.

In disaster-battered communities across Florida and North Carolina on Tuesday, registered voters turned out in droves to cast their ballots. Many said they were excited to vote, even as the storms made doing so far more challenging than they expected.

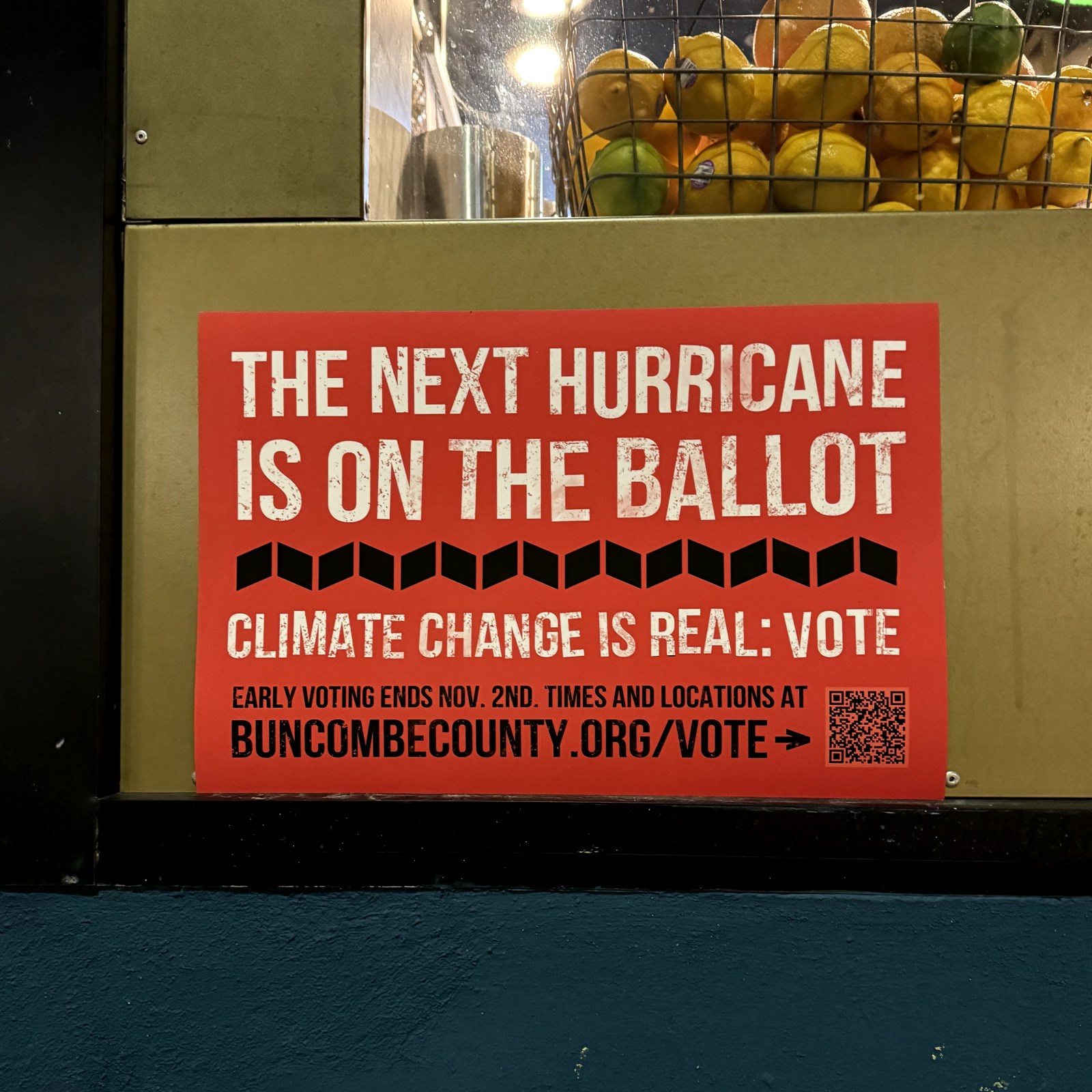

In the Asheville metro area, voters arrived at Fairview Public Library one or two at a time. A few stepped inside only to reemerge seconds later, having discovered they had the wrong location. The Fairview Public Library is one of 17 last-minute polling locations in Buncombe County, which had to scramble to reorganize polling sites after Hurricane Helene battered the region.

As a light drizzle turned to rain, Sean Miller, a 26-year-old Democrat, left the library, having just cast her ballot for Vice President Kamala Harris. Miller lost nearly all of her possessions in Helene. The storm deepened her conviction that Harris was the right candidate. “I would really like to be able to keep the National Weather Service free and accessible to everyone,” she said, referring to a Project 2025 initiative to privatize federal weather data collection. “Helene didn’t change my opinion, but it made me feel more encouraged to vote to keep basic things like that.”

Election day scenes from around western North Carolina, including a sign redirecting voters to a new polling site and a temporary dirt road. Zoya Teirstein / Grist

Stacey Troy Smith hasn’t voted since 1992, when she cast her ballot for Bill Clinton. This time, she’s voting Republican. She owns a small farm in Swannanoa, North Carolina that was destroyed by Hurricane Helene. “My fence is gone and bears have eaten half my livestock,” she said, standing in the parking lot of a last-minute polling location at Warren Wilson College. “I couldn’t seem to get any help.” Smith said that someone registered under her address and claimed the $750 relief payment that FEMA distributes to disaster victims for immediate necessities. The experience soured her on the agency and on the federal government in general. “I would definitely say a lot of people are negative against FEMA in this area,” she said.

Smith voted for Trump, but she split her ticket with some Democrats, too, she said. “In some areas, I think there should be women, but I wouldn’t vote for Kamala Harris as the first woman president.”

A few miles away, at a temporary polling place at the Art Space Charter School in Swannanoa, Sarah Mclaughlin, a 25-year-old Amazon employee, was preparing to cast her vote for Harris. “I feel like there’s an obvious choice,” she said. “Everything Trump says is the exact opposite of what I want to see happen in this country.” Mclaughlin (“I swear that’s real,” she said, referring to the fact that her name closely resembles the name of Canadian singer-songwriter Sarah McLachlan) heard the conspiracy theories that the federal government had purposefully abandoned the people of western North Carolina after Hurricane Helene hit, but she didn’t put any stock in it.

“We’re in the mountains, you don’t expect there to be a hurricane,” she said. “So of course there are going to be people who are angry because we’re not getting a response as quickly as places like Florida. I figured they would come whenever they were able to, and they have.”

In Yancey County, northeast of Asheville, board of elections officer Charles McCurry sat waiting in traffic behind a jack-knifed tractor trailer near Ramseytown, reflecting on the scale of devastation in the rural communities where he had spent the morning. “It was absolutely destroyed,” he said of Ramseytown. The local polling place was not spared.

“The voting house was a fire department, and the fire department was completely washed away during the flood,” McCurry said.

When asked about whether he’d heard misinformation about voting, McCurry sighed. “Well, in the entire area,” he said, there were “rumors about FEMA, rumors about, you know, that the storm was somehow brought on by a particular group of people to upset voting in the area, yada yada yada. This is the kind of stuff people don’t need.”

County officials erected a makeshift polling site in a tent in Ramseytown outside a small Baptist church. The site is accessible only by a newly packed dirt road, created after rising floodwaters in the Cane River washed away the highway into town. Mccurry said early voting turnout was large. On Election Day, the speed was closer to a couple of people per hour.

Zoya Teirstein / Grist

Five hundred miles to the south, voters walked into the Cuban Civic Club in Florida’s Hillsborough County. The community center was a temporary polling site for residents in precincts hard-hit by hurricanes Milton and Helene.

Jerrie Daniels waited for an Uber to pick her up early Tuesday after casting her vote. She had to figure out how to get to her new precinct this morning, an added hurdle and costly expense.

“I was sort of counting my money,” Daniels said. She also didn’t feel like she had enough information to vote for candidates and issues beyond the biggest races. The back-to-back storms and the hurdles they created didn’t change how she voted, but they “solidified,” she noted, her decisions at the ballot box. “I’m an American descendent of Black slaves,” she said. “The election for me means a big change. A better life.”

Tara Gonzalez agrees that much is at stake. The 47-year-old mother of two got emotional in the parking lot of the Cuban Civic Club voting site about what the election could mean for her and her family. “It’s so personal,” she said. “I have a 17-year-old daughter and a 13-year-old son. And to me, it’s their rights, their future.”

Gonzalez, a former teacher and union organizer, said she has been worried that the one-two punch on her community would negatively impact how people would vote, particularly on a local initiative that would increase property taxes to finance higher salaries for public school teachers and staff. “So many people were hurt by [the storms],” she said. “How can they possibly consider more… to afford a tax on their home?”

Elsewhere in Tampa, Victory Baptist Church is serving as another new polling location. Parking spots remained hard to come by all morning, lines of cars gridlocked on adjacent roads. A lifelong Floridian, Bill Butler lives down the street. The storms brought high winds, severe rain, and a deadly storm surge that slammed his Ballast Point neighborhood and damaged his house, as well as his typical voting precinct. “They moved us here after all that area was pretty much water,” said Butler.

The church also showed signs of damage: The main building’s windows were encased in plastic tarp and Butler said he suspects the interior had been flooded during Helene.

His experience with the hurricanes further reinforced his decision to vote for former President Trump. “What you like to see is people that are coming to your help as quickly as possible,” he said. “I think that Trump came to the help of a lot of people very quickly because he lives here. He knows what it’s like in Florida. And we’ve been hit pretty hard. I mean, two major hurricanes within two weeks.”

At Temple Beth-El in St. Petersburg, voters have been making their way from across Pinellas County to cast ballots. Mounds of debris still line the streets, and a pocket of storm-ravaged houses encircle the polling location.

Mike Trombley drove down to the site Tuesday afternoon from Seminole after his usual voting place in Treasure Island was decimated by Helene. Trombley has been displaced since the hurricane flooded his house with three and a half feet of water. “We got our asses kicked by Helene,” he said. He’s not sure exactly when he’ll be able to return home. He grappled with the “politicization of information” when casting his ballot. “I don’t know what I should know, and even when I do look it up, it’s like watching TV. You’re going to get a conservative or a liberal slant.”

Tampa resident Bill Butler stands outside of Victory Baptist Church, a temporary polling site for some that shows signs of damage from hurricanes Helene and Milton, including plastic covered windows. Ayurella Horn-Muller / Grist

What Trombley knows for sure is that the outcome of this election will not make much of a difference in how his community rebuilds in the months and years to come. “FEMA is a mess no matter what,” he said.

State Representative Linda Chaney, a Republican from Florida’s 61st district, was also at Temple Beth-El. Chaney, up for re-election, greeted voters in the parking lot. Severe flooding from Helene displaced both her and her 93-year-old mother from their homes.

Devastation from the storm has driven much of Treasure Island’s coastal community from their neighborhoods. Chaney said she expects that many people in the hardest-hit areas will not make it to the polls. People across the state also reported issues with Florida’s online voter resource tool intermittently crashing all morning, keeping an unknown number of people from being able to look up their current polling location.

“The majority of my district got wiped out by the hurricanes,” said Chaney. “Those folks might have a hard time coming to the polls, because they’re kind of busy. They’ve got no home, they’ve got no clothes. And then the polls got changed.” She knows of at least six people who showed up at one St. Petersburg polling location only to discover it wasn’t their new precinct.

Further north, outside of a polling station in Safety Harbor, Florida, Bill and Elizabeth Wadsworth sat in folding chairs, a cooler tucked between them, urging passerby to vote for Harris and Walz. The two considered themselves staunchly Republican until former Trump took office in 2017. Bill served in the U.S. Navy during the Cold War from 1963 to 1970. Elizabeth remembers what it was like to fight for abortion rights in the early 1970s.

“Our youngest granddaughter just turned 21,” she said. She also is worried about the security of the country under another Trump administration. “You think about them and what kind of country they’re going to inherit.” Although Milton and Helene didn’t change their polling location, or their votes, she is aware that many others across the Tampa Bay region are grappling with the voting hurdles and extensive damage left behind by both storms.

“To me, if a person wants to vote, they are going to vote,” she said.