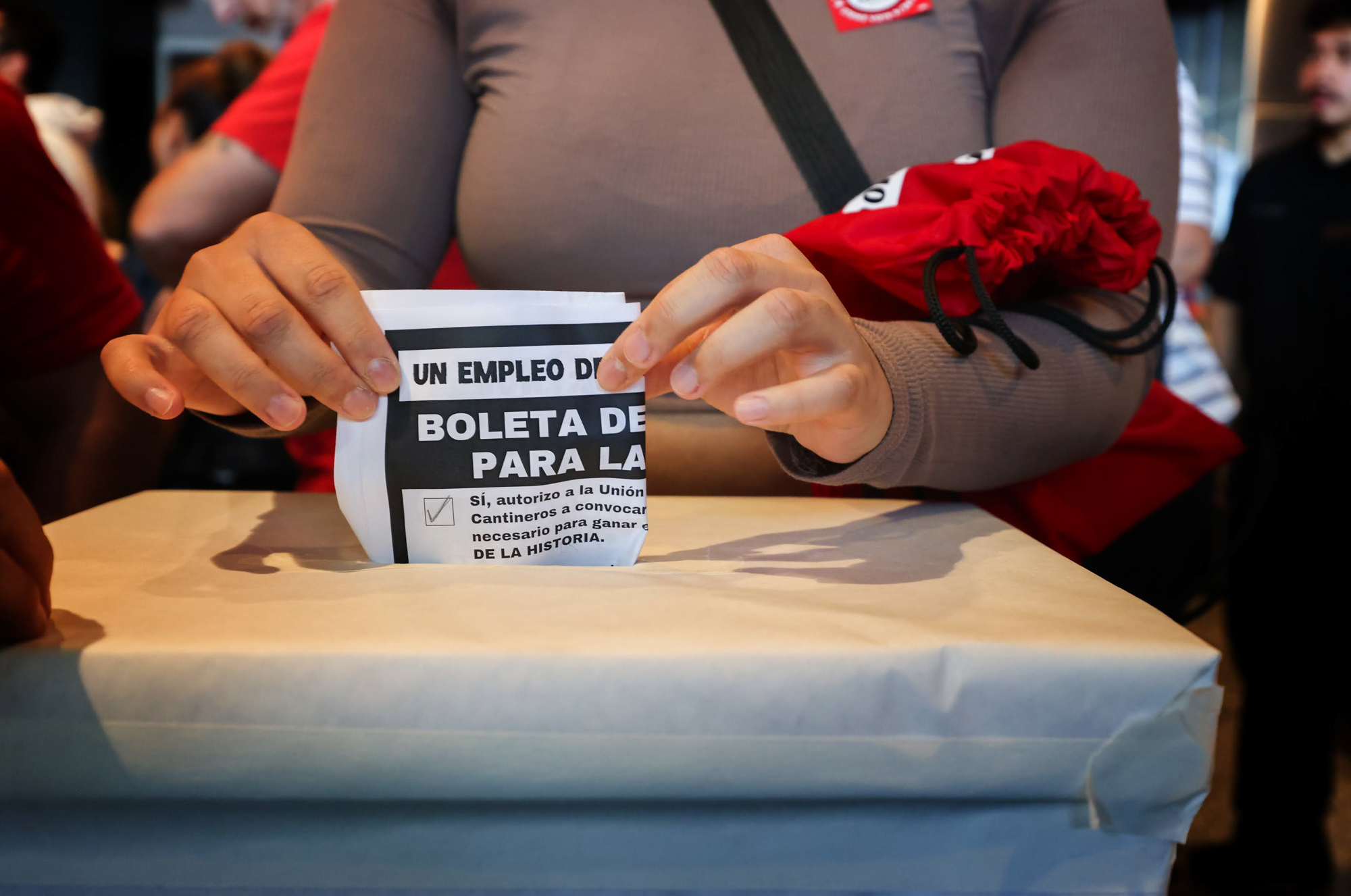

With chants of “one job should be enough,” some 10,000 members of the Culinary and Bartenders unions filled UNLV’s Thomas & Mack Center Tuesday morning for a vote to authorize the first citywide strike against the resort industry in 39 years.

Representatives of Culinary Workers Local 226 and Bartenders Local 165 said the results of the vote would authorize negotiating committees to call for a strike by some 53,000 non-gaming Strip and downtown casino employees. A vote in favor of a strike would be largely symbolic, but would give the labor leadership — who said they are negotiating with management in good faith — the ability to call for a walkout.

The results are expected to be released following a second round of voting Tuesday evening.

Most of the union members participating in the morning session and those who spoke with The Nevada Independent expressed support for the strike.

Francisco Rufino, a cook at a cafe inside Paris Las Vegas, said he voted yes because after working in the industry for more than 20 years, he is worried his salary won’t be enough to cover the increasing cost of living.

“The members of our union are determined to fight for what they want — I imagine it’s what I want, too — protection of good wages, protection of benefits and being able to provide for my family,” Rufino said in Spanish. “Wages are my biggest concern … But to be frank, it’s not difficult for me to say that I’m going to be out picketing to fight with my colleagues.”

The unions have not set a date for a strike, which could disrupt operations along the Strip and downtown. Gaming analysts said they expect some sort of deal — with double-digit wage increases over the course of a five-year contract period — to be reached before Las Vegas is in the international spotlight for the Formula One race in mid-November, although union leaders say they are not optimistic the dispute will be resolved before a walkout.

Lino Paredes, a union member who works as a banquet steward at Wynn Las Vegas, said he often feels overworked and underpaid.

“Rent, food, gas, everything is going up but our salaries aren’t,” Paredes said in Spanish. “After the pandemic, there has been an overload of work that we are experiencing throughout the city. In all the casinos, we are being overworked.”

Culinary and Bartenders workers voted to authorize a citywide strike in 2018, but the unions eventually reached new five-year agreements before any walkouts. The last citywide strike took place in 1984.

“When we had a strike vote five years ago, we had negotiations and we were able to get a contract,” Culinary Secretary-Treasurer Ted Pappageorge said following the morning vote. “I don’t know that we’re going to get to a contract this time. It does not look promising. We’re hoping for the best.”

The unions estimated between 8,000 and 10,000 members had voted in the morning session, with a similar number expected to vote Tuesday afternoon. The unions had a show of force at the end of June with a well-attended march down Las Vegas Boulevard.

Since April, the unions have been in talks with MGM Resorts International, Caesars Entertainment and Wynn Resorts, the Strip’s three largest employers, which cover 38,000 non-gaming workers. Although Caesars CEO Tom Reeg said in May to expect “a significant raise for our frontline workers,” company representatives have largely declined to comment on the negotiations.

“These companies have the opportunity to step up to the plate and do the right thing, but we haven’t seen that yet for five months,” Pappageorge told reporters after the vote. “We’d love to be able to say we have a deal. We’re not expecting it at this point.”

The contracts cover non-gaming employees, including guest room attendants, cocktail and food servers, porters, bellmen, cooks, bartenders, laundry workers and kitchen workers at roughly 50 Strip and downtown properties.

Workers concerned for their jobs

Rufino fears that his and his colleagues’ jobs — especially for bartenders — could eventually be replaced by automation. The recent MGM Resorts cyberattack forced many of the computerized jobs, such as helping guests check in and out, to be handled by a staff member the old-school way.

Rufino said seeing that ordeal made him realize that while technology cannot be stopped, companies should not depend solely on it and should not take workers for granted.

“We can to some extent learn to control that technology. We don’t say we don’t like technology, because everyone likes to have their smartphone in their hand,” Rufino said. “If companies choose technology or robots over people, instead of laying off the workers, they should have training to do another job or learn how to operate that equipment.”

Contracts between the properties and unions formally expired at the end of May, but the union said it reached an agreement on contract extensions with most Strip properties and that any wage increases agreed to in a final contract would be retroactive.

However, earlier this month, the unions said the contract extensions with MGM, Caesars and Wynn ended. While terms and conditions of an expired collective bargaining agreement covering wages, benefits and job security largely remain in place, the no-strike provisions are no longer in effect, allowing workers to walk off their jobs.

In addition to wage and benefit increases, the union is seeking numerous contract changes that strengthen job security, workload reductions, technology protections, safety and bringing more workers back to work. Neither side has given specifics about the size of their wage increase proposals.

“The pandemic has been difficult for everyone. Our members are dealing with inflation, high cost of gas, of rent, and their patience is done,” Pappageorge said. “The companies are doing extremely well. They’re making more money than they made in their histories. And they’ve got to be willing to share.”

A potential disruption

Gaming analysts who visited with Strip casino operators in the last few weeks said they believe the contracts will be settled with increases in workers’ pay before the Nov. 16-18 Formula One Las Vegas Grand Prix event, which is expected to draw tens of thousands of high-spending visitors to the Strip.

“We also expect labor contracts to be resolved in the next few months,” Macquarie Securities gaming analyst Chad Beynon wrote in a research note. He said wage and benefit increases could reduce cash flow margins slightly for some of the largest operators.

Truist Securities gaming analyst Barry Jonas met with Pappageorge and other Culinary leaders in addition to resort executives. He suggested all parties are “highly motivated to reach an agreement in October,” ahead of the Formula One race.

“A strike would have sizably negative ramifications for [MGM Resorts and Caesars] and tipped employees,” Jonas wrote in a research note. He said gaming company officials “all stated in our meetings that negotiation processes are about where they thought they’d be at this time.”

After speaking with both sides, Jonas wrote he expects workers will receive “meaningful” double-digit wage increases over the five-year contract with a higher increase in year one followed by smaller increases the next four years.

“The wider question is the union’s other points,” Jonas wrote. “A reduction in workload might have to be met by an increase in labor which could cause costs to increase ahead of base wage increases.”

He wrote that casino companies could offset costs through new technology, which he said customers are demanding. Jonas wrote that hotel room remodeling efforts could reduce the burden on housekeeping staff.

“We do think MGM Resorts’ recent cyber-attack highlights the importance of maintaining a strong relationship between operators and unions,” Jonas wrote.

The last major Culinary strike against the resort industry nearly four decades ago involved 17,000 union workers walking off the job over contract disputes with 32 Strip resorts. Unions representing bartenders, stagehand workers and musicians also walked out. The Culinary strike ended after 53 days, but workers remained off the job for another two weeks to support musicians and stagehands.

Six casinos did not initially sign new contracts but three of the properties — Sam’s Town, California and Holiday Inn (now Harrah’s Las Vegas) — eventually negotiated new agreements.