Value stocks are providing investors some shelter from the storm sweeping markets, as portfolio managers seek out bargains and dump high-flying companies that have been in vogue since the wake of the financial crisis.

The MSCI World value index has fallen around 7 per cent in 2022 on a total return basis, far better than the 25 per cent tumble for the index provider’s growth index.

The strong relative returns have meant that an investment strategy in which traders purchase shares in global companies that are cheap compared with metrics like book value and profits, and bet against groups that are expensive, has generated returns of almost 30 per cent so far this year, according to Bloomberg data.

The renaissance started over a year ago, but the so-called value factor’s powerful rise in 2022 has reinforced belief that this is now a durable shift in market conditions.

“There is a regime shift under way,” said Yoram Lustig, head of multi-asset solutions for Europe and Latin America at US asset manager T Rowe Price.

Growth investing has dominated as central banks have unleashed successive rounds of stimulus to shore up the world economy against the financial crisis in 2008 and the coronavirus crisis in 2020. The measures, including setting interest rates at historically low levels, helped inflate the prices of companies not expected to reach peak profits for years to come.

Value investors, in contrast, have struggled over the time period as their performance lagged behind.

“We survived the worst decade for value in history and now we’re enjoying the fruits of the rebound,” says Rob Arnott, founder and chair of Research Affiliates, a consultancy.

Nick Kirrage, co-head of the global value team at London-based asset manager Schroders, said that the valuations of growth stocks had become so overstretched that an eventual reversal was inevitable.

“Valuation is a bit like a big elastic band. You can stretch it so far and then it comes back. Valuations can’t expand forever, they tend to come back to a median over time.”

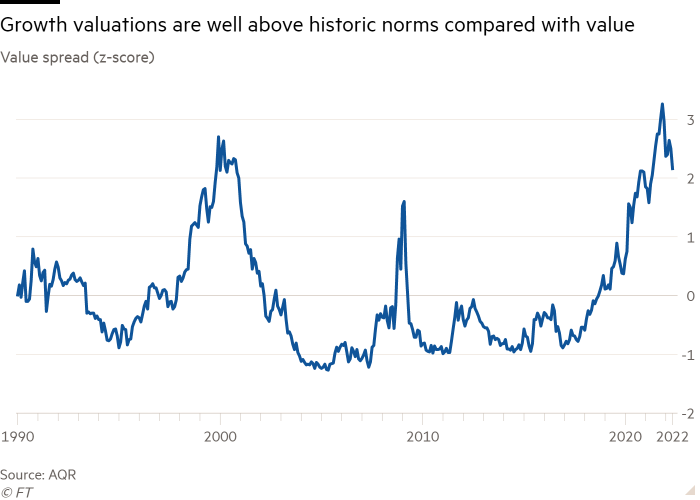

Analysis by quantitative investment firm AQR shows that the value spread — which is the dispersion between the valuation of growth and value stocks — is still nearly as stretched compared with historic norms as it was during the peak of the dotcom bubble in 2000.

“This is a giant mispricing,” said AQR Capital Management founder Cliff Asness. “I believe that the ridiculous spreads that we’re seeing mean that value is going to make a lot of money in the next three-plus years.”

Asness said that AQR has cautioned clients, nevertheless, that there are still likely to be resurgences in growth stocks along the way. “Sticking with [the value bet] when it’s incredibly painful is the source of outperformance. But we don’t think it will get back to full crazy.”

Vanguard expects US value stocks to deliver annualised returns of 4.1 per cent over the next 10 years compared with just 0.1 per cent for US growth stocks.

And a shift in sentiment is starting to be borne out in exchange-traded fund flows among US investors. US-listed growth-focused ETFs have registered net outflows of $2bn in the first four months of 2022, partially reversing the positive inflows of $38.2bn seen over the whole of last year, according to data from State Street.

Meanwhile US-listed value ETFs have gathered net inflows of $37.6bn in the first four months of the year, following $60.3bn net inflows during 2021, State Street said.

Despite this rotation, the vast majority of investors — many of whom have become conditioned to “buy the dip” in recent years — are still contemplating whether to increase their exposure to value stocks, said Richard Halle, portfolio manager at M&G Investments.

“It is emotionally difficult to take action when growth stocks have done so well for so long,” he added. “Previous rallies for value stocks since the financial crisis have been brief and actually turned out to be a signal to double down on bets on growth stocks.”

Guy Spier, chief executive at Zurich-based Aquamarine Capital, said that the current inflationary environment means that investors are favouring companies that show real earnings today, rather than evaluating some of the more imaginative metrics by which they looked at growth companies, such as total addressable market, unit economics, net earnings that exclude stock compensation costs, or even — in the case of WeWork — community-adjusted earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation.

“Money is suddenly becoming expensive and with higher interest rates, people care about what a company earns. What a concept!”

For many dyed-in-the-wool value investors, growth’s dominance over the past decade has presented an existential challenge. Spier said: “Growth investors looked at people like me, and thought oh you poor soul, you idiot, you just don’t understand how the world has changed.”

Now, with signs of a broad shift in markets, Spier said: “I do feel a certain amount of schadenfreude — it’s like, what the hell were you people thinking?” But the vindication is “bittersweet”, he said: “I would love to be putting lots more money into the market but instead my investors are also nervous, my investors also want to pull money.”