When Alex Ross moved to Texas from Portland, Oregon, the first thing he noticed was how different the colors were. “It was less green,” he laughs, when I ask him what he remembers about making the move at age six—first to DeSoto, where his father, a United Church of Christ minister, had been hired to lead a congregation, and then to Lubbock, two years later. “In the plains, everything is very much a golden color, because the sun is bleaching the grass out.”

If you’re familiar with Ross’s work as one of the most singular and recognizable comic book artists of the last thirty years, then you know how important color is to him. Ross rose to superstardom while still in his early twenties with his unique approach to comic book art, which blended the dynamism of early masters such as Jack Kirby and John Romita with the photorealistic painting techniques of twentieth-century commercial artists like James Montgomery Flagg and Norman Rockwell.

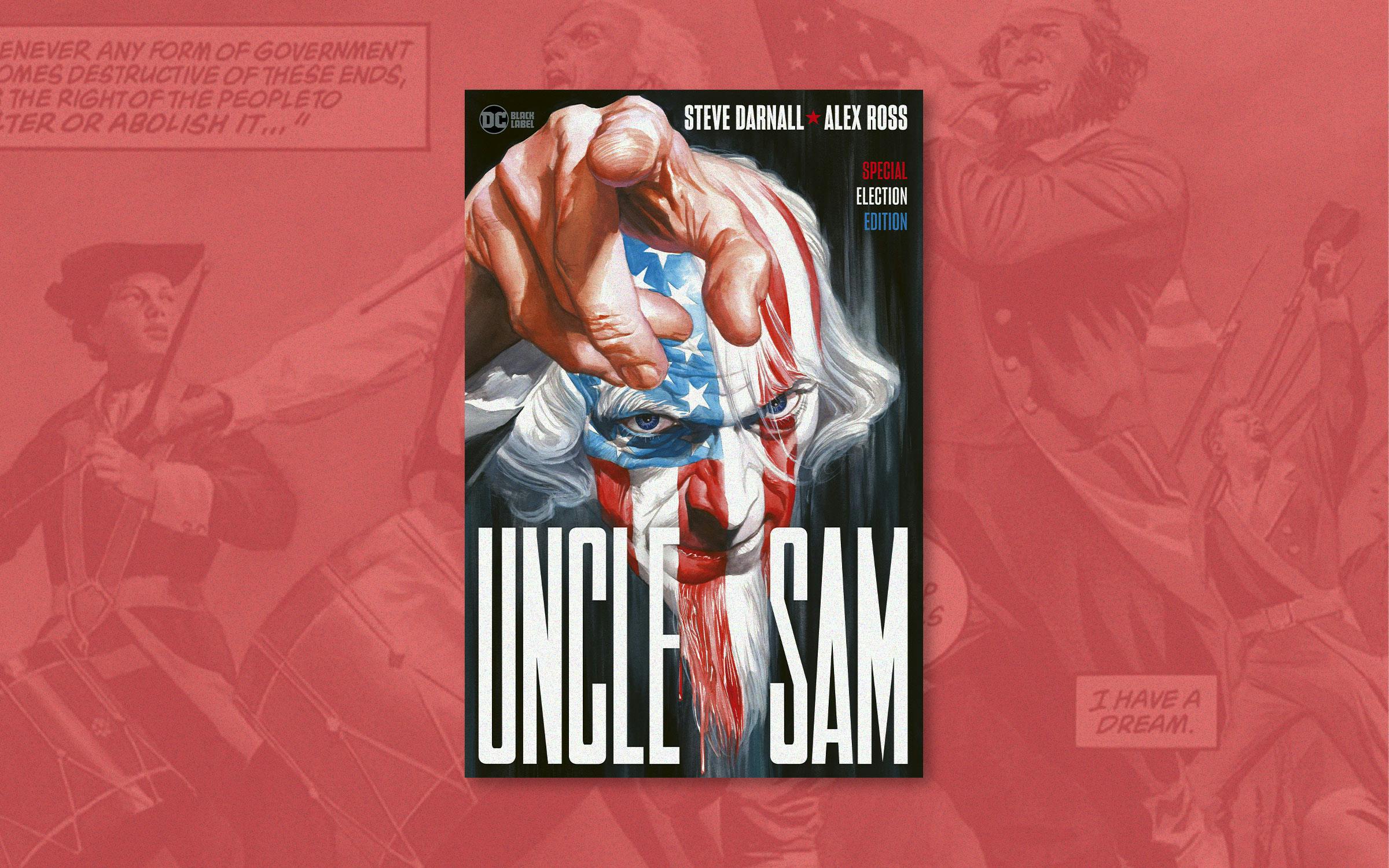

Ross drew and painted 1994’s Marvels and 1996’s Kingdom Come, which are among the most iconic graphic novels in Marvel’s and DC’s respective catalogs. His most politically charged work, however, is the 1997 graphic novel Uncle Sam. The book is a sharp departure from the superhero tales Ross is most famous for depicting—and it’s probably not a coincidence that it’s the only work from a major publisher that he fully illustrated that’s been allowed to slip out of print. Until this August, after book publisher Abrams ComicArts licensed the title from DC, it had been fifteen years since it was last available. Uncle Sam: Special Election Edition is out now, reentering the zeitgeist just as American politics may be more divisive than any point since the Civil War.

It wasn’t a matter of quality. Uncle Sam was hailed as a masterpiece upon its publication. The 1998 edition features an introduction from cultural critic Greil Marcus, and the back cover is full of praise from luminaries selected to mark the book as a serious work of art. English folk icon Billy Bragg called it “a timely idea, brilliantly executed,” while Watchmen author Alan Moore declared it “a luminous and moving study of America’s iconographic landscape.” Most of Ross’s work deals with nostalgia—when the artist depicts superheroes, they often look like the versions of the characters that existed in the sixties and seventies, and his website currently sells lithographs of renditions of the Beatles and the Monkees—but the approach Uncle Sam takes to the past is anything but dewy-eyed.

Growing up, Ross spent his Saturdays at a program for aspiring young artists at Texas Tech, and that wasn’t the only part of his weekly routine that influenced his future career. “I was a comic book addict from the second I saw Spider-Man on television as a kid,” Ross recalls. “I would beg for comics on every grocery store trip—and then I learned that there was a comic book store in Lubbock called Star Comics, and my ritual was to go there every week. It’s still there to this day.”

Ross left Lubbock when he was seventeen to attend the American Academy of Art College, in Chicago, and his career in comics commenced shortly thereafter. His first published work was a Terminator adaptation that Ross drew and painted for the now long-defunct Chicago-based publisher NOW Comics, in 1990. Then his big break: In 1994, he illustrated a limited series called Marvels, telling the story of Marvel’s superheroes through the lens of a photojournalist covering the big events in the fictional universe’s history. It became a phenomenon, earning three Eisner Awards—the comic book equivalent of the Oscars—along the way.

As Ross was working toward his breakthrough in Chicago in the early nineties, a mutual friend introduced him to another recent arrival from Texas who shared his love of comics. Steve Darnall, a native of the area who had recently returned after five years in San Antonio, where he graduated from Trinity University, had begun dating a friend of Ross’s from art school. “He worked at this comic book store downtown, so we met each other very quickly and hit it off really fast,” Ross recalls.

Darnall helped Ross develop the pitch that would become Marvels, and the two began an ongoing conversation about projects they might work on together in the future. As Ross’s star continued to ascend, he was asked to work on a limited series similar in scope to Marvels for DC, paired with one of the company’s top writers. That book, the 1996 graphic novel Kingdom Come, would go on to influence the way comics, films, and video games approached the characters of Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman for decades to come; when audiences watch Warner Bros.’ rebooted Superman next summer, the title character’s chest will bear Ross’s version of the iconic Superman S. (In 2006, Jay-Z named his comeback album after Kingdom Come, in which Superman comes out of retirement.) The work collected more Eisners, and Ross became thoroughly established as one of the industry’s premier talents. To follow it up, he pitched DC on another project—this time with Darnall as the writer. Instead of using the company’s best-known characters, the duo wanted to pluck out an obscure, short-lived World War II superhero that DC had acquired the rights to in the 1950s called Uncle Sam. The story Darnall and Ross wanted to tell was a bold reckoning with the history of America and the country’s status in the late 1990s as the world’s lone superpower, a story that eschewed superhero tropes for something that more resembled the work of Howard Zinn or Noam Chomsky. It was, to put it mildly, something of a swerve for Ross.

When Darnall and Ross’s Uncle Sam was released, I was seventeen years old, a hungry comics obsessive who spent most days after school at the local comic book store in Highland, Indiana. The shop’s owner, aware that I was looking for comics that went beyond superhero tropes, put a copy of the book into my hand. In the way that only reading the right thing when you’re seventeen can do, it opened my mind to entirely new ways of thinking about myself as an American, about comics as an art form, and about aspects of my country’s history I had never previously considered. I came away an evangelist, convinced that everyone should read it.

I wasn’t alone. It sure seemed like Ross, a star at the top of his game, and Darnall, a newcomer to comics with a voice uncommon in the industry, had created yet another classic destined to live on bookstore shelves next to Kingdom Come, Marvels, and other elevated, literary graphic novels such as The Dark Knight Returns, Maus, and Watchmen. And then the book more or less disappeared.

Uncle Sam isn’t an easy read. It’s political, but it seems to disdain both Bill Clinton’s and Ronald Reagan’s Americas equally. It’s nonpartisan in how it apportions blame for what it sees as the nation’s refusal to reckon with the less inspiring parts of its history—starting with the violent end to Shays’s Rebellion, in 1787, continuing through decades of slavery and a century and counting of its aftermath, and going on through the Cold War and beyond. The story is told impressionistically; the character of Uncle Sam—if you’re picturing the one in the famous James Montgomery Flagg painting of a bearded man in a star-spangled top hat pointing his finger and saying “I Want You,” you’ve got the right one in mind—stumbles through the streets of New York, homeless, attacked, and seeking meaning. The book is never entirely clear about whether this is the real Uncle Sam, which the story posits as the spirit of America, or just a guy who kinda looks like the one on the poster.

Darnall approaches the comic book form deftly, peppering Sam’s dialogue with quotes from leaders throughout American history, from Thomas Jefferson’s “tree of liberty” to Chicago mayor Richard J. Daley’s “The police are not here to create disorder; they’re here to preserve disorder.” His abstract approach to the character’s inner monologues dovetails with Ross’s painted pages, which reimagine shameful parts of America’s history—lynchings, assassinations, the handling of the AIDS crisis, and more—in a style that looks eerily like the Americana style of Norman Rockwell, creating an effect that’s both hallucinatory and grounded. The superhero plot of the book, to the extent that there is one, involves our bedraggled, beleaguered protagonist seeking out a smirking doppelganger wearing his top hat to battle for the soul of America.

“One of the things that struck me in the early nineties was that we had spent the previous decade sort of living in two Americas,” Darnall told me when I asked him about the impetus for the book. “There was the shining city on the hill that Ronald Reagan was telling us about, and then there was the one we were actually seeing, which had gun violence and homelessness. And Alex hit on the idea that if there’s two Americas, there’s probably two Uncle Sams.”

While Uncle Sam calls readers to confront ignoble aspects of American history they may not have been taught in school, its ultimate theme is that the response to those past events is to strive to be a better, fairer, and more just country that lives up to its founding ideals. I didn’t feel ashamed of America while reading Uncle Sam. I felt hopeful that the country’s future might be better than its past.

I asked Darnall why he thought a book with that theme, acclaimed in the mainstream as a masterpiece and illustrated by one of the biggest names in the industry, could have ended up out of print just a few years later, nearly as forgotten as poor Sam himself.

“One of the phrases people have thrown my way about this book is the word ‘radical,’ and I didn’t ever see it that way. We were two young men who were really concerned about a country whose ideals mean a great deal to us, and we were seeing them distorted and wanted to draw attention to that,” Darnall told me. “But I guess I wouldn’t be surprised if in the early twenty-first century it made people a little gun-shy.”

Critically reflecting on America and its ideals had a bit of a moment in the late nineties, but by mid-September of 2001, such critiquing was almost entirely out of fashion. A “you’re with us or you’re with the terrorists” mindset didn’t leave a lot of room for nuance; just ask the Chicks, or any of the lawmakers who wanted to rechristen the french fries in the congressional cafeteria “freedom fries.” In comics, too, a certain type of jingoism seeped into the pages. Marvel responded to 9/11 by presenting images of supervillains weeping at Ground Zero.

“We were perfectly primed for the knowledge that the sales on this weren’t going to rival Kingdom Come. We realized this was more an acquired taste, but we also felt like if there’s somebody who’s thinking the way we’re thinking, we want them to know they’re not alone,” Darnall said. Even so, the fact that the book slipped out of print for years surprises him. (One hardcover reissue, in 2009, also fell out of print.) “The fact that an Alex Ross book went out of print, to me, that’s astonishing. You can leave my name out of it, but that’s like kicking Johnny Cash out of the studio.”

No one I talked with could quite tell me why the book wasn’t treated like, say, its DC companions V For Vendetta and Watchmen. Leadership at DC changed over the years, and it’s possible that the new executives just weren’t drawn to the material. Karen Berger, who oversaw the Vertigo imprint at the company at the time Uncle Sam was published and who was the editor on the book back in 1997, told me she struggled to explain it. “It should have been [treated better],” she said. “Is it because it examines a lot of dark truths about the country? But a lot of comics examine dark truths about the country. I can’t really answer that. I just know that it should have been.”

Like its protagonist, though, Uncle Sam is getting a chance to make a comeback. The book has always had its adherents, and last year Ross heard from Abrams ComicArts, the publisher of literary-minded comics such as Run, by civil rights legend John Lewis, and the graphic novel adaptations of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road and Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower. Abrams was, he learned, in negotiations with DC to license the rights to Uncle Sam. “I was thrilled to hear it, but I had no idea it was even possible that they could work out a publishing deal to get it back in print,” Ross said.

The resulting book is heavier than the paperback copy that’s been on my bookshelf since I was in high school. It’s a hardcover with a dust jacket painted by Ross, and the interior pages prove that printing technology has improved over the past 27 years. It includes two new essays at the end, one from Darnall and one from Ross, reflecting on the series.

I hadn’t reread Uncle Sam in more than twenty years when I got my 2024 edition, and as with revisiting anything that meant a lot to me as a teenager, I approached it with some trepidation. Would I find myself embarrassed that my younger self found it so moving? Would the themes that seemed so relevant in 1997 feel dated now?

There are some aspects of the book that read slightly differently in the current context. Shays’s Rebellion, which features heavily in the story, has gone from an obscure event in early American history to something debated as a possible precursor to the insurrection of January 6. References to the Kennedy assassination, conspiracy theories around which were primarily the territory of the left back in 1997, are now more commonly heard on the right. But the book’s themes hold up well—if anything, there’s a depth to Uncle Sam that comes from Darnall’s thorough research and Ross’s kinetic cartooning that I appreciate more as an adult than I was equipped to as a teenager.

The issues at the heart of Uncle Sam haven’t changed in the decades since the book was published. In fact, they’re probably more pronounced now than they were then. In the late 1990s, the idea that there were two competing visions of America rang true, but it wasn’t necessarily reflected in our politics. In a debate during the first presidential election cycle after Uncle Sam was published, the two candidates voiced their agreement with each other nearly a dozen times, something unthinkable in the age of Trump. The idea of the past as a force that shapes America’s present was, in the era of The End of History, one that needed some explaining; these days, whether one is eager to return to the past to make America great again or to reckon with it because we’re not going back, the role the past plays in our politics is clear.

“When we were doing Uncle Sam, we were jaded young men, with all the self-righteousness that implies,” Darnall said. “It’s encouraging now to see, in recent years, people being forced to reevaluate what it is they’re patriotic towards. What is it about the country they’re proud of? Is it just the fact that it exists? Or is it the idea of liberty and justice for all? I know it’s simple. It’s basic. It may sound like a cliché. But we’ve seen more clearly that this democracy is an amazing thing, and a fragile thing. Perhaps it’s not always been equally valued by everyone. But that in itself is worth pursuing, and worth perfecting. And that’s something in the book that can still resonate after all those years.”

When you buy a book using this link, a portion of your purchase goes to independent bookstores and Texas Monthly receives a commission. Thank you for supporting our journalism.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, a portion of your purchase goes to independent bookstores and Texas Monthly receives a commission. Thank you for supporting our journalism.