[ad_1]

This article is an onsite version of our Europe Express newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday and Saturday morning

Good morning and welcome back to the Financial Times’ Europe Express Weekend newsletter. This week I’m asking whether Ukraine — and, for that matter, Georgia and Moldova — will one day join the EU.

By upturning Europe’s security order, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has given real urgency to this question. Or so you might think. In truth it’s a question that, in the short term, isn’t going to get a clear-cut yes or no answer from the EU’s 27 member states.

On Tuesday Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky tweeted that he’d spoken with President Emmanuel Macron of France and “held a substantive discussion of our application for the status of a candidate for EU membership”. He was silent on Macron’s response.

Understandably so. A week earlier, Macron said in Strasbourg that, even if Ukraine were granted candidate status, it would take “several decades” before it could join the EU.

That will be true, if the EU continues to treat candidates with its time-honoured mix of bureaucratic hurdles and protection of the national interests of existing members.

But Ukraine’s citizens are fighting and dying for the very same values and way of life that the EU believes itself to embody. Richard Youngs writes for the Carnegie Europe think-tank that to rebuff Ukraine’s bid “would sap the EU’s claim to any kind of moral clarity in its foreign policy for years to come”.

In an interview with the FT, Ukrainian foreign minister Dmytro Kuleba put matters even more bluntly:

If we don’t get the candidate status, it means only one thing, that Europe is trying to trick us. And we’re not going to swallow it.

Ukraine’s application splits EU governments down the middle. Broadly speaking, those in central and eastern Europe that once languished under Soviet control are in favour of Ukraine’s admission. The enthusiasm of governments in western Europe is, shall we say, more tepid.

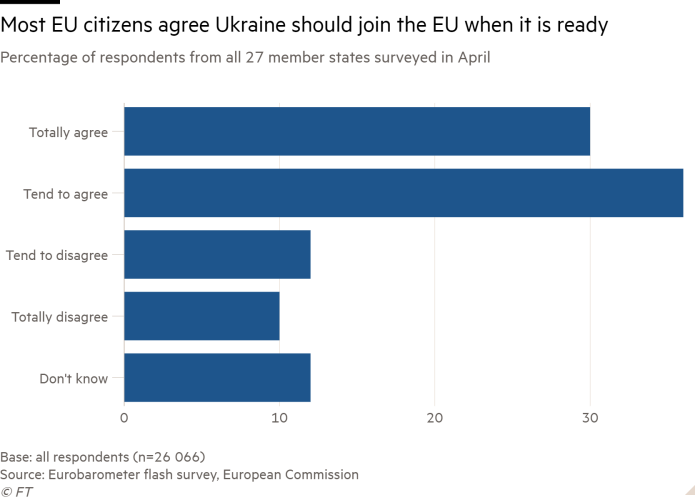

On the whole, European public opinion is more positive about Ukraine. A Eurobarometer survey, conducted by the European Commission, indicated that 66 per cent of respondents thought Ukraine should join the EU “when it is ready”, 22 per cent were against and 12 per cent didn’t know.

These numbers conceal some telling national differences. For example, only 48 per cent of Hungarians backed Ukraine’s entry. Every other country registered a majority in favour. Could that reflect the longstanding dispute between Viktor Orbán’s government and Kyiv over the ethnic Hungarian minority in western Ukraine?

But the most important disagreement is between western European capitals and those to the east. To put this into perspective, we need to go back to a speech delivered by François Mitterrand, France’s then president, on December 31 1989.

Reacting to the collapse of communism in eastern Europe, Mitterrand didn’t call for the admission of the newly liberated countries to the EU (as the European Economic Community became in 1993).

Instead, he proposed the creation of a “European confederation” — a looser association of states that, in effect, would exclude central and eastern Europe from a core club of western European countries pursuing deep integration.

Like so much French foreign policy after the second world war, Mitterrand’s initiative was all about searching for a way to bind and contain Germany in a project of ever closer European union. In Mitterrand’s view, to bring the central and eastern Europeans into this project risked diluting it and, in the long run, expanding Germany’s power at the expense of France.

Mitterrand’s plan failed, but it has resurfaced several times during Macron’s presidency, albeit under a different guise. In Strasbourg Macron called for a “European political community” — a way for Ukraine and others to be linked to the EU, and retain the right in principle to join it, but perhaps to be kept out indefinitely.

For sure, formidable obstacles stand in the way of EU entry for Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova. They are far from meeting many EU norms and standards, and each has been territorially dismembered at Russia’s hands since the end of the cold war.

Friction between Ukraine and Georgia doesn’t help — Kyiv withdrew its ambassador from Tbilisi soon after the outbreak of war.

The European Commission is due next month to give its opinion on the trio’s membership bids. What do you think? Should Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova become full, equal EU members? Vote in our poll here.

Notable, Quotable

We have no animus against the Russian people . . . But as a country that has fought the war of independence, we know that you have to stand up to a bully in case your sovereignty is being compromised. This is exactly what the Ukrainians did — Greek prime minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis

Speaking at Georgetown University in Washington, Mitsotakis draws lessons from Greece’s 19th-century liberation from Ottoman rule.

Tony’s picks of the week

-

The US is preparing to vault into a new era of supercomputing, but national self-congratulation is conspicuous by its absence. Why? Because China got there first and is pulling out all the stops to keep its lead, writes Richard Waters, the FT’s US west coast editor

-

How should Europe recalibrate its policies towards China in the light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and rising US-Chinese tensions? Ian Bond, François Godement, Hanns W Maull and Volker Stanzel offer a penetrating analysis in this paper for the Paris-based Institut Montaigne

Recommended newsletters for you

Are you enjoying Europe Express? Sign up here to have it delivered straight to your inbox every workday at 7am CET and on Saturdays at noon CET. Do tell us what you think, we love to hear from you: europe.express@ft.com. Keep up with the latest European stories @FT Europe

[ad_2]

Source link