There is no story like it in the annals of true crime. A 7-year-old California boy is kidnapped off the street. Eight years later, he reappears at a police station, shattered but alive. And nearly two decades after that, the boy’s brother goes on a brutal killing spree in Yosemite National Park.

“Bad things happen to everybody,” Ashley Stayner says in the new Hulu docuseries “Captive Audience,” “but for our family, it’s unreal.”

There is no quick way to tell the history of Steven and Cary Stayner, and there is no way to tell it without the stories intertwining.

Steven was born in Merced in 1965, the third of five children in the Stayner family. Their childhood, until his disappearance, was typical of the era. His parents taught him to trust adults implicitly and to respectfully follow their instructions. On Dec. 4, 1972, a strange man approached Steven on his walk home from school. The man told Steven that it was alright for him to pick him up, as Steven’s mother had given him the OK. Steven got in the car.

The man was Kenneth Parnell, a convicted child rapist. He soon told the confused Steven that he had legal custody of him; Parnell said the Stayners didn’t want him anymore. Within a week of being abducted, young Steven was calling him dad.

Parnell renamed him Dennis Parnell, and moved him around frequently, living for stretches in Santa Rosa and Comptche in Mendocino County, among other spots in California. Steven attended school intermittently, and classmates remembered him as shy and sweet, although he never let anyone drop him off directly at his home. He always asked to be let off at the bottom of the driveway.

On Feb. 13, 1980, with Steven quickly growing into adolescence, Parnell kidnapped another boy, 5-year-old Timothy White, and began abusing him. Although Steven had free rein to escape at any time, he’d repeatedly stayed with Parnell, unsure of how to return home or get help. But upon seeing Timmy, Steven knew he had to act. When Parnell left a few weeks later for his job as a night security guard, Steven grabbed Timmy and headed for the road. A passing car picked up the boys and drove them to Ukiah, Timmy’s hometown, where Steven found a police station.

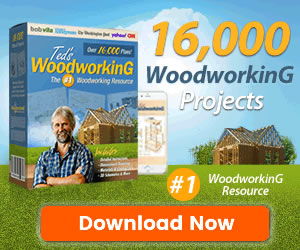

Timmy White, 5, sits on the lap of Steven Stayner, 14, and tries to blow a balloon up during press conference after their rescue in 1980.

Bettmann/Bettmann ArchiveTimmy, whose face was on the news every day, was immediately recognized as a kidnap victim. But it took police a little while to put together that Steven, who could only partially remember his real last name, was Merced’s most famous missing child: Steven Stayner.

Steven’s heroism — and his defeat of incredible odds — made him a national sensation. Images of him with Timmy were splashed across every nightly news broadcast. A made-for-TV movie went into production.

The only one who was seemingly unimpressed was Steven’s 17-year-old brother Cary. According to interviews revealed on “Captive Audience,” Cary stressed that Steven’s actions were blown out of proportion by the media and that anyone with a conscience would have done what Steven did. He admitted to being jealous of his brother’s stardom.

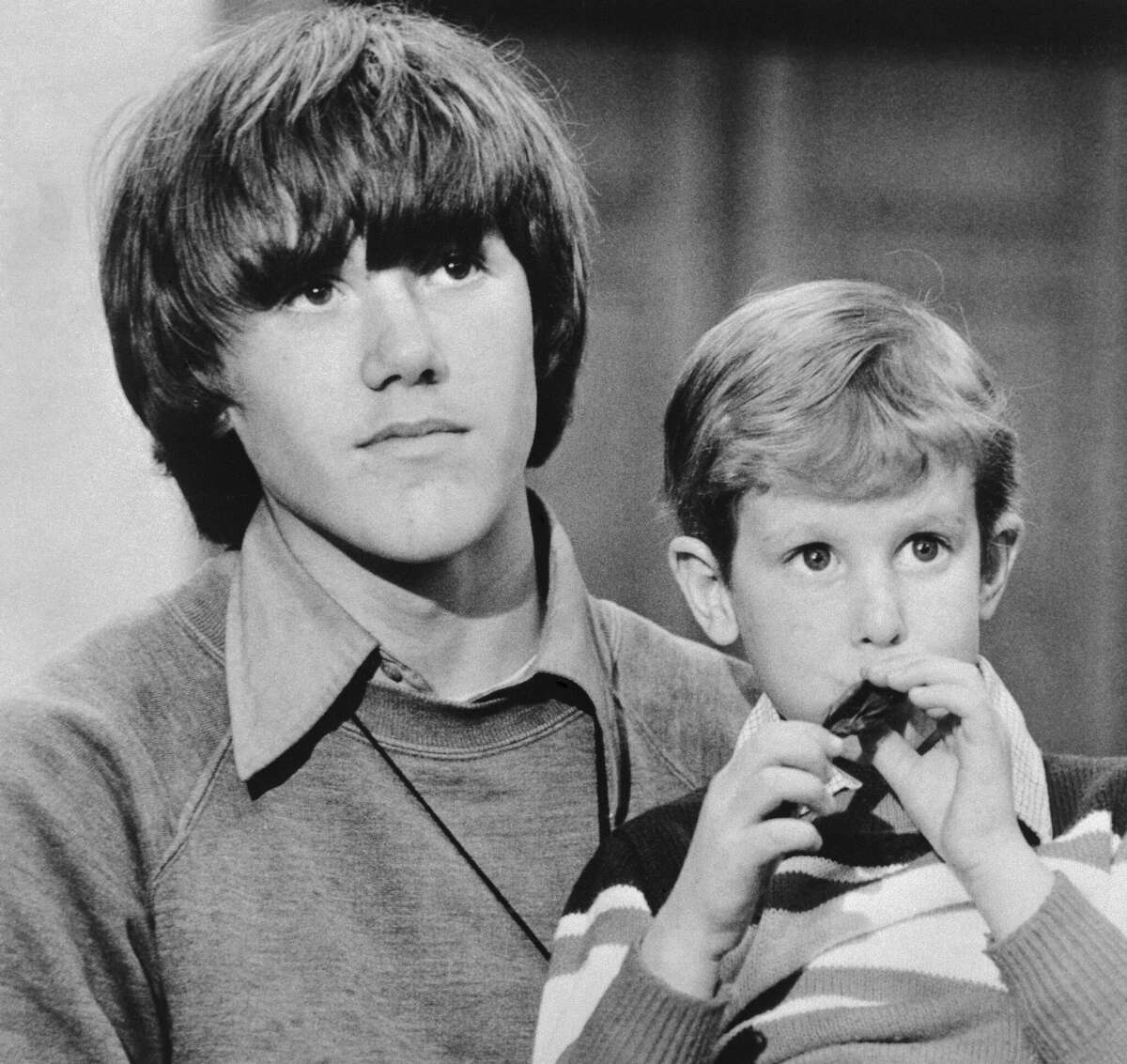

It was a hard period for everyone, though. Steven struggled to readjust to the family he barely knew and chafed against their rules, as Parnell had basically left him to his own devices. The media dogged Steven, even at school, and Steven’s father resisted the idea of his son getting help from mental health professionals. But as Steven grew into adulthood, he found some semblance of normalcy. He married and had two kids, Ashley and Steven Jr.

Then, on Sept. 16, 1989, Steven was riding his motorcycle home from work when he was struck by a driver who allegedly blew through a stop. He died from his injuries, devastating the still-healing family once again. Steven was just 24.

Steven Stayner, 23 at the time of the photograph, sitting on lawn with his wife, Jody, and young children, Ashley, left, and Steven Jr.

John Storey/Getty ImagesThe worst, if possible, lay ahead.

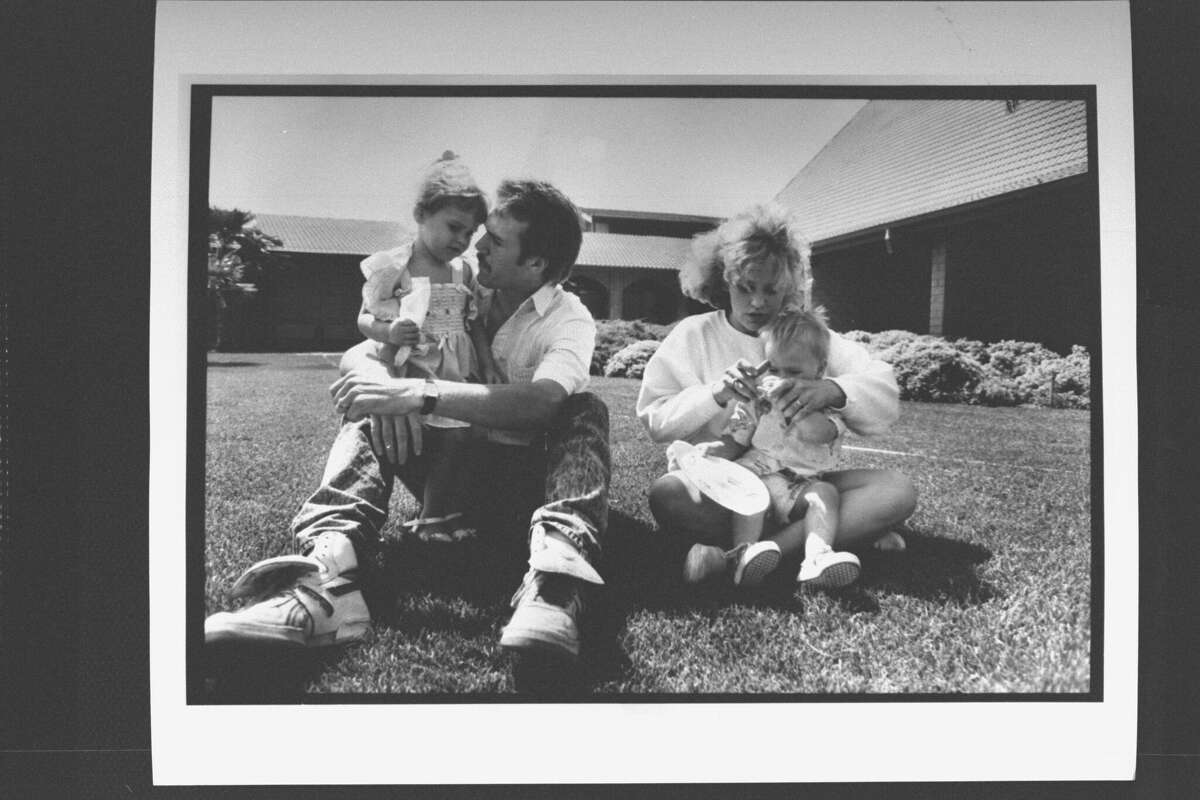

Some of the most gripping moments of “Captive Audience” come in episode three, when Steven’s now-adult daughter Ashley recalls watching the news of multiple Yosemite murders on television. As a seventh grader who lived in nearby Merced, she was gripped by the brutal slayings of tourists Carole Sund, 42, Juli Sund, 15, and Silvina Pelosso, 16. Carole Sund had taken her daughter and friend Silvina to see Yosemite National Park before Silvina returned to Argentina. The trio shared a room at the Cedar Lodge in El Portal, from which they vanished in February 1999.

The three women had been missing a month when the burned bodies of Carole and Silvina were discovered in their rental car. Then, a letter arrived for police with a hand-drawn map pointing to the location of Juli’s body, left near the Don Pedro Reservoir. Her throat had been slit.

On July 22, 1999, the decapitated body of Yosemite naturalist Joie Ruth Armstrong was found in a stream by the cabin where she lived. A witness recalled seeing a light blue 1979 International Scout at the scene earlier; they told police, who traced the car to the handyman at the Cedar Lodge: Cary Stayner.

In a photograph taken by Juli Sund that was released by Francis Carrington, Carole Sund, left, is shown with Silvina Pelosso, right, in their room at the Cedar Lodge in El Portal near Yosemite shortly before they were killed in February 1999.

AP Photo/Juli Sund, Carrington FamilyStayner had been questioned and released in the triple homicide, but now the net drew in again. Two days after the discovery of Armstrong’s body, Stayner was tracked down at a nudist colony in Wilton and arrested.

While in custody, Stayner agreed to talk to Bay Area TV reporter Ted Rowlands. The confessions rolled out. From the time he was young, he fantasized about hurting women. The girls in the motel room gave him his opportunity; he said he entered their room with the ruse of pretending to check for a leak.

Once inside, he pulled a gun on them and said he wanted their car and cash. He locked the teens in the bathroom while he murdered Carole Sund. He sexually assaulted the girls, then killed them as well. As for Joie Armstrong, he’d also met her by chance and learned the woman lived alone in the park. Armstrong fought him fiercely, causing him to sloppily leave behind footprints and tire tracks. Rowlands recalls in “Captive Audience” that, as a condition of confessing, Stayner demanded Rowlands help him get a TV movie made about his life.

For the Stayners, it was one more unfathomable tragedy. Ashley, who had followed the story on the news every day, remembered her parents sitting her down to tell her that “Uncle Cary” had been arrested for the murders. The news was devastating; most of the family members interviewed for “Captive Audience” either declined to talk about Cary altogether or would only speak briefly about the case.

Cary Stayner was found guilty and sentenced to death in 2002. He is currently on death row at San Quentin.

Cary Stayner, center, is led into the Mariposa Courthouse by Mariposa County Sheriff Sgt. Rich Parrish, left, and jail officer Sean Land on Monday, June 11, 2001. (AP Photo/The Fresno Bee, Craig Kohlruss)

CRAIG KOHLRUSSThe stories of Steven and Cary Stayner are impossible to tell separately. “Captive Audience” tries — its goal is to help distinguish Steven and his experiences from the horrors that came long after his death. But, for most people, the docuseries will leave many unanswered questions.

Did the trauma of Steven’s kidnapping shape Cary in such a way that he became a murderer? Most multiple murderers are a mixture of nature and nurture, born with a predisposition toward violence that turns into action when the wrong combination of environmental factors merge in their childhoods. It could well be that Cary would have always ended up a killer. But with an event so traumatic in his childhood, it’s hard not to wonder what could have been different for every member of the Stayner family.

“I think that a lot of people have their thoughts about my family and who we are as people,” Steven Stayner Jr. says early on in “Captive Audience,” “and I think they have it wrong.”

They do, no doubt. And it’s likely that “Captive Audience” will only elicit more speculation about the Stayners. But anyone claiming to understand their ordeal is wrong; there will never be enough answers to explain how one child survived a nightmare — and the other created one.