Haulage companies that spent last year battling to hire drivers now have a new problem: a shortage of trucks.

On both sides of the Atlantic, rising wages have helped lure workers back on the road after a lack of drivers strained the industry to breaking point, leaving shipping containers stranded at ports on the US west coast and petrol pumps running dry on British forecourts.

But a longstanding shortfall of equipment — due originally to coronavirus restrictions and chip shortages — is becoming more severe as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine shuts down the supply of key components and Chinese lockdowns threaten further turmoil in global supply chains.

“The driver has been the biggest constraint of the last two years . . . The bigger supply constraint now is the truck, and to some extent the trailer,” said Tim Denoyer, analyst at Indiana-based ACT Research.

Rico Luman, an economist at ING, said some European truckmakers were taking no more orders because their backlogs were already long, while others could not quote a price because they were unsure of the cost of raw materials for vehicles that might be delivered “far into” next year.

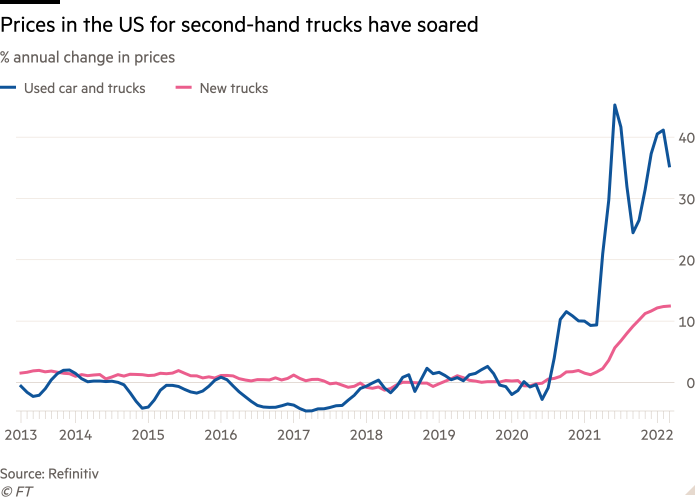

“Trucks one to two-years-old are almost the same price as new ones at the moment: there is no option B to get spare capacity,” Luman said.

“We are struggling to keep the UK fleet on the road,” said Kieran Smith, chief executive of the recruitment agency Driver Require, who said vehicle availability at the operators with which he works had dropped noticeably because of a lack of spare parts.

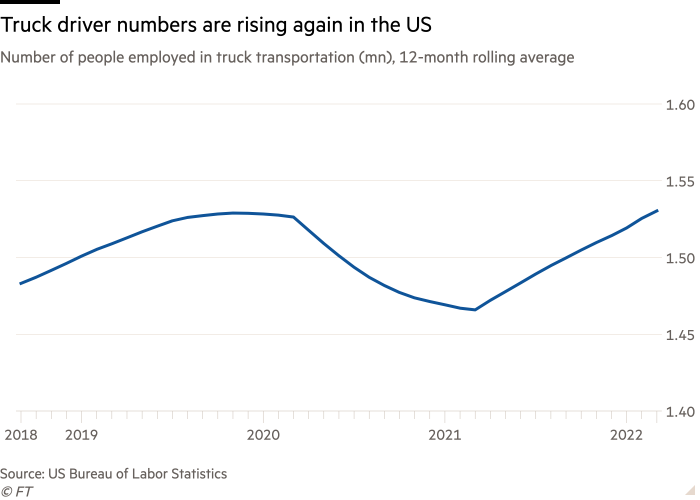

Higher pay — wages across the industry rose about 25-30 per cent over the past year, according to Denoyer — and the easing of the Omicron coronavirus wave has alleviated worker shortages in the US.

The wave of new workers, meanwhile, has helped cap costs for companies transporting their goods by truck. US dry-van spot rates, excluding fuel, fell abruptly in March and are down more than a third since the start of the year.

The picture is similar in the UK, where industry associations say driver shortages have eased as pay has improved, testing for HGV licences resumed and large-scale government-backed training schemes got under way.

“A year ago we were bleeding drivers all over as a result of Covid,” said Rod McKenzie, head of policy at the Road Haulage Association. “Now things are really easing.” McKenzie estimated a shortfall of 100,000 drivers had dropped to about 65,000.

Luis Gomez, president of XPO Logistics Europe, said vacancies in the company’s UK business had fallen and wages had stabilised across the industry, with job applicants giving priority to shift patterns that offered a better work-life balance over large pay packets.

Paul Day, chief executive of Turners Soham, a Cambridgeshire based trucking and warehousing company, said the UK market was “close to equilibrium” between the number of drivers and the amount of work, with wages in his own business up about 15-20 per cent year on year.

But he and others believe the haulage industry is able to cope chiefly because rising prices for goods, combined with bottlenecks in manufacturing, have taken the edge off demand.

“We’ve avoided the worst because ironically the economy slowed down,” said Day, who said the volume of goods moved by supermarkets had tailed off, although demand in construction was still solid.

Ken Hoexter, an analyst at Bank of America, said shippers in the US were also reporting weaker demand as fuel prices soared and manufacturers had less work to do on rebuilding their inventories, which dropped to low levels during the pandemic.

However, the industry remains fragile. Although hauliers generally pass on changes in fuel prices, they face cost pressures for other raw materials. The price of Ad Blue, an anti-pollutant used in diesel engines, has quadrupled because its key ingredient is sourced from Russia, said Day. Small operators caught in drawn-out negotiations with customers could swiftly run into cash flow difficulties.

Though the driver shortage is less acute, the industry has not solved endemic problems with recruitment and retention of an ageing workforce.

“We’re in the slower part of [the] year . . . and we’re operating close to the edge,” Smith said, adding that conditions could worsen as demand picked up during the traditionally busier summer months. “It will be really tight . . . We’re not far away from another shortage.”