Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here

Only a few of the embryos derived from all-male cells went on to develop into healthy mouse pups.Credit: Ciobaniuc Adrian Eugen/Alamy

Researchers have made eggs from the cells of male mice — and shown that, once fertilized and implanted into female mice, the eggs can develop into seemingly healthy, fertile offspring. The approach, announced yesterday at the Third International Summit on Human Genome Editing in London, has not yet been published and is a long way from being used in humans. It is an early proof-of-concept for a technique that raises the possibility of a way to treat some causes of infertility — and even allow for single-parent embryos.

Special neurons in the throats of mice notify the brain of an influenza infection, triggering behavioural changes, such as decreased movement and feeding. The throat cells contain a receptor for prostaglandins — chemicals that are made in infected tissues — and can tell the brain exactly where an infection is occurring. Before the “paradigm-shifting” study, it was unclear exactly how the brain became aware of sickness in the body. The work “flips previous thinking on its head”, says sensory biologist Ishmail Abdus-Saboor. More such dedicated neural pathways could exist, including ones that detect gut infections and trigger nausea.

Yesterday, the US House of Representatives kicked off the first in a series of public hearings that aim to investigate whether the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus arose arose from contact between people and animals or leaked from a laboratory in China. But the hearing contained more political theatre than discussion of scientific evidence. Republican committee members pushed the idea that public-health leader Anthony Fauci tried to quash investigations into a lab leak, while Democrats questioned the credibility of a witness. “I’m very much concerned that people are allowing themselves to be guided by their emotions, intuition and historical precedence,” says microbiologist David Relman.

The influential Pasteur Institute in France will cease to co-lead an infectious-disease institute in Shanghai that it established in 2004 in partnership with the Chinese Academy of Sciences. What initiated the break-up isn’t clear. Some researchers think it reflects a larger trend of China ending an era of internationalization. Others think it simply an individual case and will have minimal impact on virology research in China, which is now one of the country’s strengths.

Environmental DNA extracted from marine sediment has given scientists a blow-by-blow account of 200 years of habitat destruction in Italy’s Bagnoli Bay. The technique reveals how construction in the nineteenth century of steelworks, an asbestos plant and a causeway led to the disappearance of seagrass meadows and the marine life that depended on them, even though no ecosystem surveys were conducted at the time. “This is a very powerful tool,” says aquatic ecologist Eric Capo.

Reference: Environment International paper

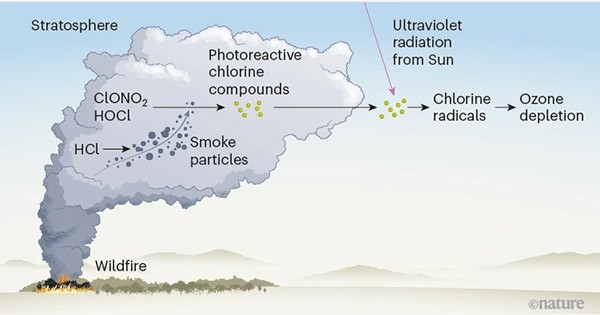

Huge wildfires that raged across Australia in 2019–20 unleashed chemicals that chewed through the ozone layer. The wildfire smoke combined with harmless remnants of now-banned chlorinated compounds, reactivating their ozone-eating form — a reaction that doesn’t usually happen in the warm air away from the poles. More-frequent wildfires resulting from climate change could expand and prolong the hole in the ozone layer, which protects Earth from harmful ultraviolet rays.

Smoke particles from intense wildfires can enter the stratosphere, where they can absorb hydrogen chloride (HCl) gas, derived mostly from the breakdown of anthropogenic chlorofluorocarbon compounds (not shown). This allows the particles to catalyse the conversion of other chlorine-containing gases, such as chlorine nitrate (ClONO2) and hypochlorous acid (HOCl), to ‘photoreactive’ chlorine compounds. When irradiated by ultraviolet light from the Sun, the photoreactive compounds produce chlorine radicals that catalytically destroy ozone, depleting its concentration in the stratosphere. (Nature News & Views | 7 min read, Nature paywall)

Features & opinion

How do COVID-19 restrictions affect harvests in sub-Saharan Africa, and how will Germany’s move away from Russian gas influence fertilizer production? Questions about how food systems respond to shocks can be explored with ‘digital twins’ — models that are hooked up to real-world data about food production, transport, processing and consumption. Most of this information already exists, says food-systems scientist Zia Mehrabi. Now it’s a question of putting together the pieces. “With real-time insights, we could see key fragilities in food systems before it’s too late,” he says.