The first anniversary of Russia’s assault on Ukraine has been greeted with soaring rhetoric. Notably, US president Joe Biden stated in Warsaw that “Our support for Ukraine will not waver, Nato will not be divided, and we will not tire. President Putin’s craven lust for land and power will fail. And the Ukrainian people’s love for their country will prevail.” These sentiments are admirable. But is the commitment genuine? Will they in fact do whatever is needed to ensure Ukraine’s survival as an independent democracy?

Even those who demand a negotiated settlement should realise by now that a necessary condition for this outcome is the realisation by Vladimir Putin that the west will not allow him to absorb Ukraine into his empire. His army’s failures over the past year may have caused him some doubts over his ability to do so. But still he believes that Russia will prevail. That is not even an unreasonable view, given the relative size of the principal adversaries and Putin’s control over the human and other resources of his country. The only force able to turn the tide for good is a combination of Ukrainian determination with western resources, both military and financial.

As Biden explained, there are powerful reasons for granting that support. This is particularly true for Europe. Putin’s assault threatens the core values and interests on which postwar Europe is built: inviolability of frontiers; peaceful co-operation among states; and democracy. It particularly threatens the security of the countries closest to Russia, which were, not long ago, inside the Soviet empire. If Putin wins, who comes next? No line can be drawn between our values and our interests, whatever “realists” suggest. Our values are our interests. This war is for a way of life built on the ideal of freedom from destructive coercion by thugs like Putin. This makes it our war, too.

Unfortunately, western rhetoric is not yet matched by deeds. This renders the outcome of the war in doubt. Justin Bronk of the Royal United Services Institute has recently written: “Russia can be beaten on the battlefield this year, and deterred from future aggression, but only if Europe stops underestimating Russian resolve; accepts that it is in a long-term military contest with an aggressive and determined enemy; and invests now in industrial capacity and support to Ukraine at the scale that the stakes demand.” Nor are military resources all that is required. Ukraine needs to sustain its people and its economy. It needs, right now, to rehabilitate its infrastructure, as Russia destroys it. Yet Russia is physically unscathed. Its economy has also survived western sanctions better than many had hoped, just as Ukraine has survived militarily better than many had feared.

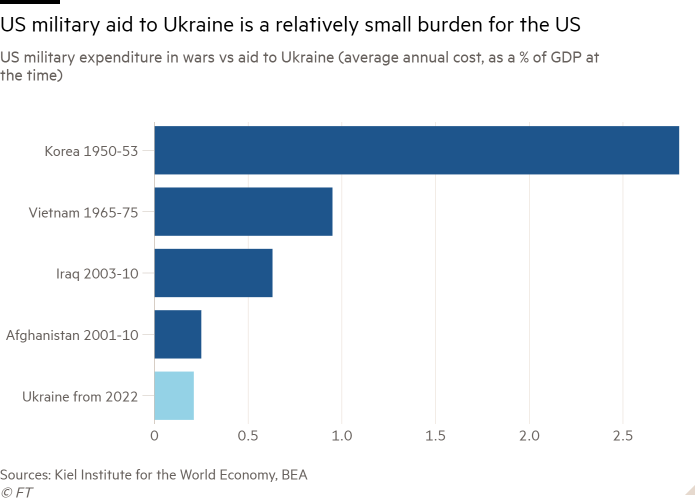

The Ukraine Support Tracker from the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, recently discussed by Adam Tooze, provides disturbing information on how limited the support for Ukraine has in reality been, especially from Europe. In particular, it notes that US commitments have so far exceeded those of EU members, bilaterally and collectively, even though the war is of far greater significance for the future of the latter than for that of the former. If one takes bilateral commitments plus the cost of supporting refugees as a share of gross domestic product, countries of eastern Europe (Poland, Latvia, the Czech Republic, Lithuania and Slovakia) have been much the most generous. The US is overwhelmingly the most important supplier of military equipment. But its aid to Ukraine is dwarfed by what it spent directly on the Vietnam or Iraq wars and matched by what it spent in Afghanistan. Again, the domestic energy subsidies of European countries dwarf their help to Ukraine. Germany, for example, has allocated 7.2 per cent of its GDP for domestic energy subsidies compared with just 0.4 per cent in total assistance to Ukraine.

Putin could reasonably conclude that Ukraine will not get the resources it needs to sustain the war in the longer run. He might also reasonably hope that he will get greater military support from China. Time, then, is ultimately on his side.

The west has to prove that this is wrong and it needs to prove this sooner rather than later if the war is not to drag on forever. There must be a recognition that this war is a vital national interest of European countries if they wish the stability and prosperity of postwar Europe to endure. Together with the US, they must mobilise the resources, including military ones, needed to win it. If this is not done more generously, it is hard to see how the war can end on terms with which Europe will wish to live.

Times indeed have changed. Peace can no longer be assumed in Europe. Russia is preparing for a long and costly war. So must the west. In the process, it will also have to reconsider its policies towards other countries. There is no doubt that the past behaviour of western countries has undermined their legitimacy in much of the developing world. This is also quite understandable, given the history of foolish wars, the failure to mobilise vaccinations on a suitable scale in response to Covid, the failure, too, to provide adequate financial assistance to these countries in response to the pandemic and the economic fallout from the war. Such indifference has inevitable costs.

At the same time, the west must make clear that the outcome of the Ukraine war is seen as a vital interest, whether other countries like it or not. It will assess the behaviour of other countries, big and small, accordingly. In calculating how to behave, the latter need to understand that the west is indeed resolved that Ukraine will emerge from the fire democratic and independent. That is, one hopes, also the truth.