This is the second part in a new FT series, Brexit: the next phase

When the UK signed its first major post-Brexit trade deal with Australia last summer, the then trade secretary (and later prime minister) Liz Truss proclaimed it was a “win-win” that would slash tariffs, lower prices and improve choice.

But a year and a half after that jubilant announcement, the trade pact has been criticised by a series of politicians and officials who believe errors were made in the push to secure a UK-Australia deal signed by the culmination of the G7 summit in June 2021.

With Rishi Sunak now pledging to take a more patient approach to signing deals — including with India and membership of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership — business groups and trade experts are warning the UK must be more strategic when cutting future agreements, while also doing more to win public support at home for international trade.

According to multiple senior Whitehall officials, the Australia trade agreement was rushed through due to the hard political deadline set by Truss, combined with a lack of negotiating expertise and experience. “We were trying to move too fast, with not enough care,” one senior civil servant said.

The result was a pact that experts believe was tilted in Australia’s direction — and was particularly advantageous for its farming industry — because of the desire to get the first major post-Brexit deal over the line. George Eustice, the former environment secretary, admitted last month the deal “gave away far too much for far too little in return”.

As well as 71 rollover agreements that maintained current trading relations with scores of countries, Australia was set as an early target for the first “from scratch” deals — along with Japan and New Zealand — by Liam Fox, the first post-Brexit trade secretary.

When Truss arrived at the newly established post-Brexit Department for International Trade in July 2019, she was eager to complete the deal with Canberra to show the benefits of leaving the EU.

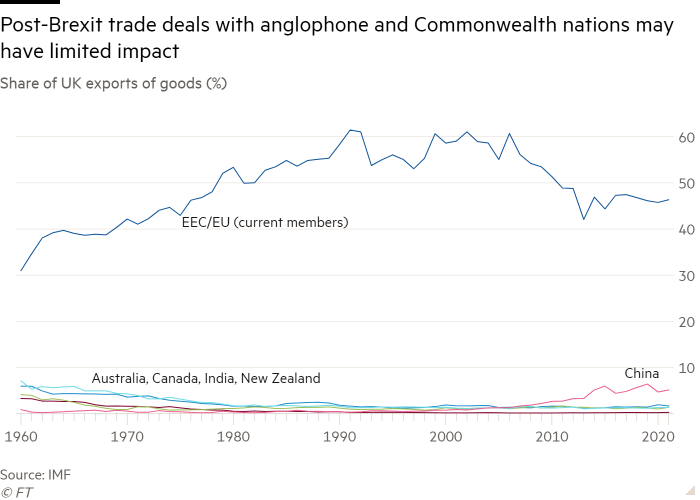

Economically, the agreement was of very modest value — an increase of just 0.08 cent in GDP by 2035, according to the government’s own early estimates — but symbolically it was a huge prize for Brexiters seeking tangible proof of the pulling power of “Global Britain”.

According to insiders at the DIT, Truss’s arrival put “rocket boosters” on the Australia talks. In a harbinger of the approach that would later be seen during her brief, disastrous stint as prime minister, the trade secretary sought to “move fast and break things”, according to one civil servant.

But the National Farmers’ Union has lambasted the agreement as a “one-sided” deal that granted Australian producers too much access to the UK market for too little in return — something that Eustice later admitted in a letter to then prime minister Boris Johnson seen by the Financial Times.

“We cannot risk another outcome such as Australia where the value of the UK agri-food market access offer was nearly double what we got in return,” Eustice wrote last June, warning Johnson not to repeat the same mistake in negotiations with India.

In his letter Eustice told the then-prime minister that the Cabinet Office had “watered down” previously agreed Whitehall safeguards that would have enabled ministers from other departments to push back if the DIT made concessions they considered to be too deep.

Of particular concern for British farmers was the government’s decision to ignore NFU lobbying to ensure that beef and lamb quotas were based on “carcass weight equivalent”, which calculates quotas including skin, bone and blood, effectively reducing them in size.

The NFU said the deal with Australia also left open the possibility that Australian producers could ship container-loads of quality cuts — steaks and joints — that could very quickly distort the UK market for high-end products.

Although the effects are difficult to immediately predict, the deal left the UK vulnerable to a sudden shift in Australian export policy if Canberra was cut out of other major markets, such as China, according to Nick von Westenholz, the NFU’s director of trade.

“The UK government has reserved itself almost no recourse to managing imports if they start proving harmful to UK farm livelihoods,” said von Westenholz.

In a bid to rein in the government, the NFU launched a petition calling for more protection for farmers and for UK food standards. It won the backing of celebrity chef Jamie Oliver and garnered more than 1mn signatures.

Environmental and animal welfare lobby groups are now pressuring the government on future deals, demanding that it maintains a “level playing field” for food and animal welfare standards in future post-Brexit trade agreements in a letter to new trade secretary Kemi Badenoch last October.

Trade groups are also demanding that parliament has a greater say over the ratification and agreeing mandates for ministers to future trade deals.

While farmers have yet to feel the ill effects of the Australian trade deal, they are well aware of its potential to disrupt their market. They are also dealing with other Brexit-related concerns, including an overhaul of farm subsidies, border delays for paperwork and stringent, time-consuming checks on exported animal products.

Officials who worked on the UK-Australia trade deal insist that its benefits will emerge in the medium term. “You have put the deal in perspective, it was taken as part of a wider approach that included stabilising our EU relationship, stabilising trading relations with a whole series of other countries,” one government insider said.

Another argued that the geopolitical impact of the agreement was important. “Australia is a very significant economy — they’re Five Eyes members and have respect for rule of law. The deal will add £2.5bn to the UK economy forever once implemented, £900mn to UK wages that wouldn’t have existed and half a billion on services trade. The Australians will make gains but we will gain much more proportionately.”

The DIT said the Australia pact would “unlock” £10bn of new bilateral trade. “We have always said that we will not compromise the UK’s high environmental, animal welfare or food safety standards and the deal includes a range of safeguards to support British farmers,” it said in a statement.

DIT officials and ministers also say privately they are eager to learn the lessons of the deal with Australia and avoid the same errors with future trade agreements — including a pact with India and membership of the CPTPP, which Sunak has made a priority.

But Sam Lowe, trade policy partner at Flint Global, warned that the rush to conclude the Australia deal had dented public confidence in trade policy and set unhelpful precedents for future negotiations.

“The key lesson . . . for the government is to remember that when cutting these deals, you need to always be looking over your shoulder, because cutting an unpopular deal now makes future deals more difficult,” he said.

Lowe added that it was already possible to see the fallout from the Australia deal both at home — where the issue is playing on the doorsteps of farming constituencies in south-west England — and in negotiations with other countries.

“The UK is currently renegotiating its bilateral deals with Canada and Mexico that were rolled over from EU membership and the talks have been slowed down because Canada in particular is asking for similar concessions on agriculture that were granted to Australia,” he said.

Canada’s desire to leverage concessions during the negotiation has also played into the UK’s attempts to join the Pacific trade grouping, the CPTPP, which officials concede have now slipped into next year.

As well as CPTPP members such as Canada seeking to wring concessions from the UK, they also have one eye on China’s accession process, Lowe added, and are wary of granting the UK membership without full compliance with the groups rules in case it was taken as a precedent by Beijing.

According to Eustice’s letter to Johnson, the key lesson for the UK in future trade talks is not to rush. “I am aware that India is a tough negotiator but I firmly believe the UK should be too,” he wrote.