As a just-out-of-college reporter for the Dallas Morning News in 1979, I watched a landmark event in Texas history unfold, though it would be years before I understood its significance. That November, a former sixth grade teacher from Dallas named Don Baker filed a class action federal lawsuit (Baker v. Wade) challenging Texas’s notorious “Homosexual Conduct” law, known throughout the state’s gay communities simply by its state statute number, 21.06.

Gay activists across the country had made strides in the seventies, as twenty states repealed their sodomy laws during that decade. But Texas went the other direction by passing the homosexual conduct law in 1973, making “deviate sexual intercourse” a crime punishable by a fine. A nonprofit called the Texas Human Rights Foundation wanted to challenge the law, but it needed someone to become the public face of the cause—to show that gay Americans were not deviants, but hardworking, churchgoing, even rodeo-loving folks. Don Baker, a Navy veteran, former Boy Scout, and devout Christian who had recently come out during an awkward but captivating local TV news interview, would become that front man.

The seventies were still the dark ages for most Texas newspapers when it came to gay rights. As a straight reporter, I hardly noticed the casual homophobia in the newsroom or that the article about Baker’s groundbreaking lawsuit, written by our federal courts reporter, didn’t make the front page. As late as 1986, the Morning News editorial page was still saying sodomy laws were a states’ rights issue and should be left alone by the U.S. Supreme Court. When Baker v. Wade was filed, the newspaper’s editors had little reason to think the lawsuit would become momentous or that gay Texans and their advocates would one day celebrate Baker for his uncommon courage.

Baker was never a news source of mine, but we chatted occasionally if we saw each other at official events or around the Oak Lawn neighborhood of Dallas, where we both lived. He was fit and about five foot eight, with round, scholarly glasses and a businesslike, coat-and-tie style that friends say matched his commitment to “the Dallas Way,” a white male establishment code of sorts that emphasized political decorum and consensus over confrontation and fiery rhetoric. He quickly grew into his role as an activist, winning over more conservative gay Texans and gaining the confidence of straight reporters and business leaders. A longtime college friend of his recalled that at gay organization meetings, Baker developed a natural stage presence and would gesture emphatically as though channeling his grandfather, a fiery preacher from an Oak Cliff Assembly of God church.

“He was the perfect plaintiff,” recounted Dallas attorney Jim Barber, now 84, who helped the Texas Human Rights Foundation find someone who had a clean arrest record, could deal with reporters, and had the fortitude in court to withstand lengthy questioning about his sex life. (Baker’s friends said he seldom dated.) It didn’t hurt that Baker, who was born in Oak Cliff in 1947, had been honorably discharged from the Navy in 1974 after joining at the height of the Vietnam War and was also deeply religious, though he often felt abandoned by the Assembly of God church. After interviewing six or so other candidates to be the lead plaintiff, Barber knew “Don was our man the moment I talked to him.”

Baker had been tormented by his identity when he enrolled at East Texas State University, in Commerce, in 1965, and later at the University of Texas at Austin, where he met other gay students but could not bring himself to act upon his feelings (as his sister Maggie Watt later told University of North Texas historian and author Wesley Phelps). I heard a similar story from a college friend of Baker’s, who later became a Dallas lawyer (and who didn’t want to be named). “We absolutely did not know each other was gay in 1965, but later I would learn from Don that we were both struggling with mental health issues in college,” he said. “Back then, we perfected ‘passing’ in the straight world.” Phelps says in an episode of his documentary podcast Queering the Lone Star State that Baker thought coming out might mean rejection by his large family and worried that his homosexuality might condemn him to the Bible’s everlasting hell. “I was dying inside,” Baker later told a Morning News reporter. “I thought, ‘How could a good little Christian boy from Oak Cliff be such a criminal?’ ” When he transferred to the University of Texas at Austin, he said he had his first furtive experience of flirting with another man, but that moment only brought on more self-loathing and desperate attempts to date women.

Frustrated and questioning his faith, Baker joined the Navy and served in Germany and Guam, working in communications. After he was honorably discharged, he followed a Navy buddy to the State University of New York at Cortland. While studying there, he decided to go to a meeting of a gay organization at Cornell University, in Ithaca, some twenty miles away. It took him more than an hour to work up the nerve to enter the meeting, stopping on a balcony above the gay students so he could simply see from afar what he would recall as the first group of people he knew were just like him. At age 27, Baker was cautiously opening the closet door.

His struggle consumed him. For the next year, he immersed himself in history, psychology, and sociology texts while earning a degree in education, still hoping he could reconcile his identities as devoutly Christian and gay.

After returning to Dallas in 1976, Baker came out to his parents, who sought out psychologists and ministers for guidance and were eventually told by the family doctor, “Just love him. He’s your son.” So they did. As Baker’s confidence grew, he took some risks that were unusual for a gay man in the late seventies in Texas. After Dallas Independent School District superintendent Nolan Estes proclaimed in late 1977 that he would fire all gay teachers, Baker, who was then teaching at a Dallas elementary school, agreed to speak anonymously, with his face obscured, to a Dallas TV reporter:

Narrator: Because of a secret he keeps from the elementary schoolchildren he teaches, he asked that his identity be withheld. The secret he keeps from his students and colleagues alike is a sensitive one: he is a homosexual.

Reporter: Can you give me a conservative estimate of how many gays are on faculties at area schools?

Baker: There are perhaps around five hundred teachers in the Dallas Independent School District whose sexual orientation is homosexual.

Though it’s been widely reported that Baker was fired after the interview, this appears to not be the case. Phelps, the UNT historian, researched the matter extensively and could find no evidence Baker was fired; Baker’s sister and two friends agree but also told me he was under pressure to quit. “I think Don being fired is a better story, but I don’t think it actually happened,” Phelps said. What is certain is that the threatened gay witch hunt within Dallas schools never happened, and Baker’s supporters on the DISD board let Estes know it was they who had the final authority to fire teachers.

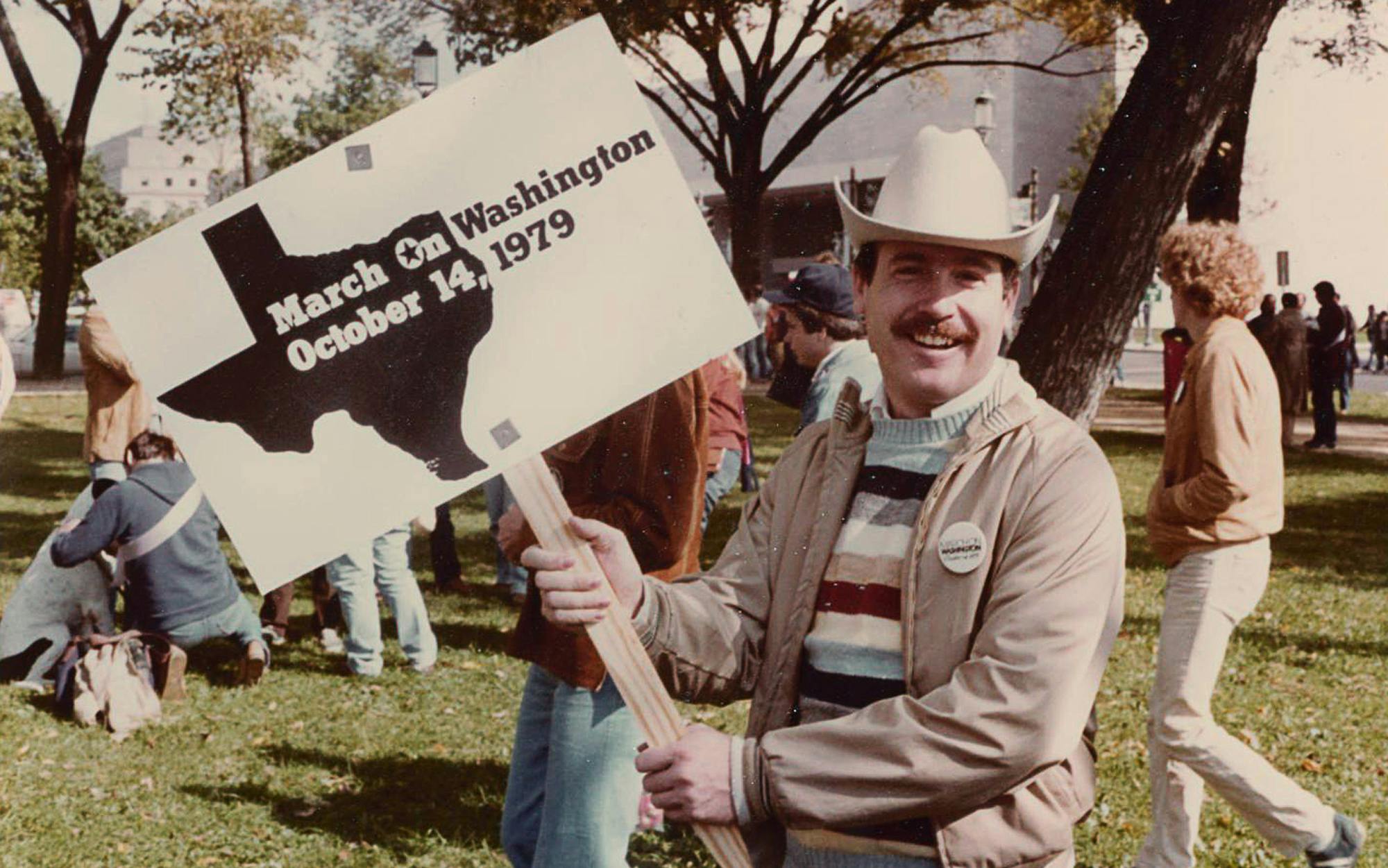

In June 1978, Phelps writes in Before Lawrence v. Texas: The Making of a Queer Social Movement, the not yet fully out Baker attended the fifth annual Texas Gay Conference, in Dallas, and was energized by the conference’s keynote speaker, San Francisco city supervisor Harvey Milk, who, five months later, along with San Francisco mayor George Moscone, was murdered in city hall by a fellow politician. With the Milk killing and numerous arrests by Dallas police of gay men at bars and in public parks as a galvanizing backdrop, Baker became active in the Dallas Gay Political Caucus and within a year became president of the organization, later renamed the Dallas Gay Alliance. Baker channeled his energy into fund-raising, DGA political affairs, and gay events—he even served as the grand marshal of the Texas Gay Rodeo Association—rather than picketing and street protests. He was constantly trying to drum up support and book guest appearances at benefits, typing letters to celebrities such as singer Bette Midler, comedian Joan Rivers, actor Marlo Thomas, Yale historian John Boswell, and Harvard legal scholar Laurence Tribe.

The size and success of many of those fund-raising events might have led outsiders to think that the Dallas gay movement in the seventies and eighties was headed for mainstream acceptance and, at least, some measure of safety, but an ever-present homophobia still defined the daily lives of Baker and his supporters. “Many of us used aliases back then,” recalled Baker’s old college friend, who worked alongside Baker in the DGA. “It was like Germany in the 1930s. We thought at any time the Dallas police might break into our Monday night meetings in Oak Lawn and seize our membership rolls.”

As with many historic court decisions, Baker v. Wade required a lot of waiting. After the filing in November 1979, Baker toured the state. His speeches and appearances helped the Texas Human Rights Foundation raise money for legal needs, such as bringing in expert trial witnesses including Judd Marmor, a renowned UCLA psychiatrist who fought to remove homosexuality from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Almost three years after Baker joined the lawsuit, on August 17, 1982, U.S. district judge Jerry Buchmeyer found in Baker’s favor, ruling that statute 21.06 represented an unconstitutional violation of the fundamental right of privacy and that the prohibition against homosexual sodomy was “without any rational basis.”

Baker, then 35, joined hundreds of gay men and women who filled the streets of Oak Lawn to celebrate what the activist called “the Magna Carta, Declaration of Independence, and the Emancipation Proclamation all rolled into one for our people.” “This ruling,” he also said, “is truly a victory for the American way of life, a way of life that supports and encourages tolerance, pluralism, and understanding among people.” Behind the scenes, says Barber, the lawyer, he and Baker would receive anonymous death threats in the coming months. But Baker could also find some levity in telling a lawyer joke I’ve borrowed many times. “You know the definition of a great attorney?” he’d deadpan. “Somebody who can get a sodomy charge reduced to following too closely.”

Baker’s victory, however, would prove short-lived. While Texas attorney general Jim Mattox had no interest in appealing Buchmeyer’s decision, the district attorney in Amarillo, Danny Hill, went to the federal Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans—far more more liberal then than now—to challenge the federal judge’s ruling. Hill lost before a three-judge panel in September 1984, and Baker v. Wade stood as the law of the land until Hill was able to get his appeal heard by the Fifth Circuit’s entire sixteen-judge appellate court. Such rehearings were rare in federal court, but Hill was given one in February 1985. In August of that year, the court overturned Buchmeyer and reinstated the Texas sodomy statute.

Set free for three years, gay Texans were again criminals in the eyes of the law. In 1986, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear Baker v. Wade. Phelps, the historian, reports that Baker was so dismayed that he wrote to Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall, the only justice who voted to hear the case. “I laid my life on the line for a cause I deeply believe in,” wrote Baker. “For seven years, my people labored with me on this case. It is very difficult to just let go after seeing it end so abruptly.”

At 39, Baker was exhausted and privately despondent, telling a Dallas reporter that same year that he wanted to learn Spanish, take piano lessons, and be known as something more than a gay political activist. Some budding relationships had never blossomed because of his being so recognizable in public. “Many gays saw me as being more than human,” he said. “The expectations they had of me were not the expectations they had of other people.” Baker did eventually find romance and left Dallas for Boston, where he would move to be with his partner, a former priest named Michael Hartwig. At a going-away party at Baker’s apartment in Oak Lawn, Barber hugged his tearful client. “Don was crushed that he lost,” Barber told me. “I don’t think he fully recovered. . . . He was outstanding. Very brave. Very courageous.”

Baker was always well aware he could lose his case. He just hoped it would lay the foundation for more lasting change, which finally came in 2003, when the Supreme Court ruled in Lawrence v. Texas that all state sodomy laws were unconstitutional and would be invalidated. As with other overshadowed civil rights pioneers, Baker’s greatest contribution may have simply been in being first and perhaps giving other gay Texans the courage to stand up for their rights in their workplaces, schools, and hometowns.

“He knew what he did was important,” said Baker’s sister. “It was not in vain.” Don Baker died of bladder cancer in 2000, three years before the landmark Supreme Court decision establishing the rights he had worked so hard to secure.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, a portion of your purchase goes to independent bookstores and Texas Monthly receives a commission. Thank you for supporting our journalism.