It’s high July in Mason, in the heart of the Hill Country. Several thousand have turned out for the town’s annual rodeo roundup parade, a splendidly small-time procession that circles the county courthouse twice before dispersing into a subworld of barbecue, corn dogs, funnel cakes, and handicrafts. Flags flutter. Floats rumble by featuring the camo-themed Yonker Brothers Meat Market & Processing, the rodeo queen’s court, and, in case you have forgotten what part of the country you are in, “Texans for Trump.”

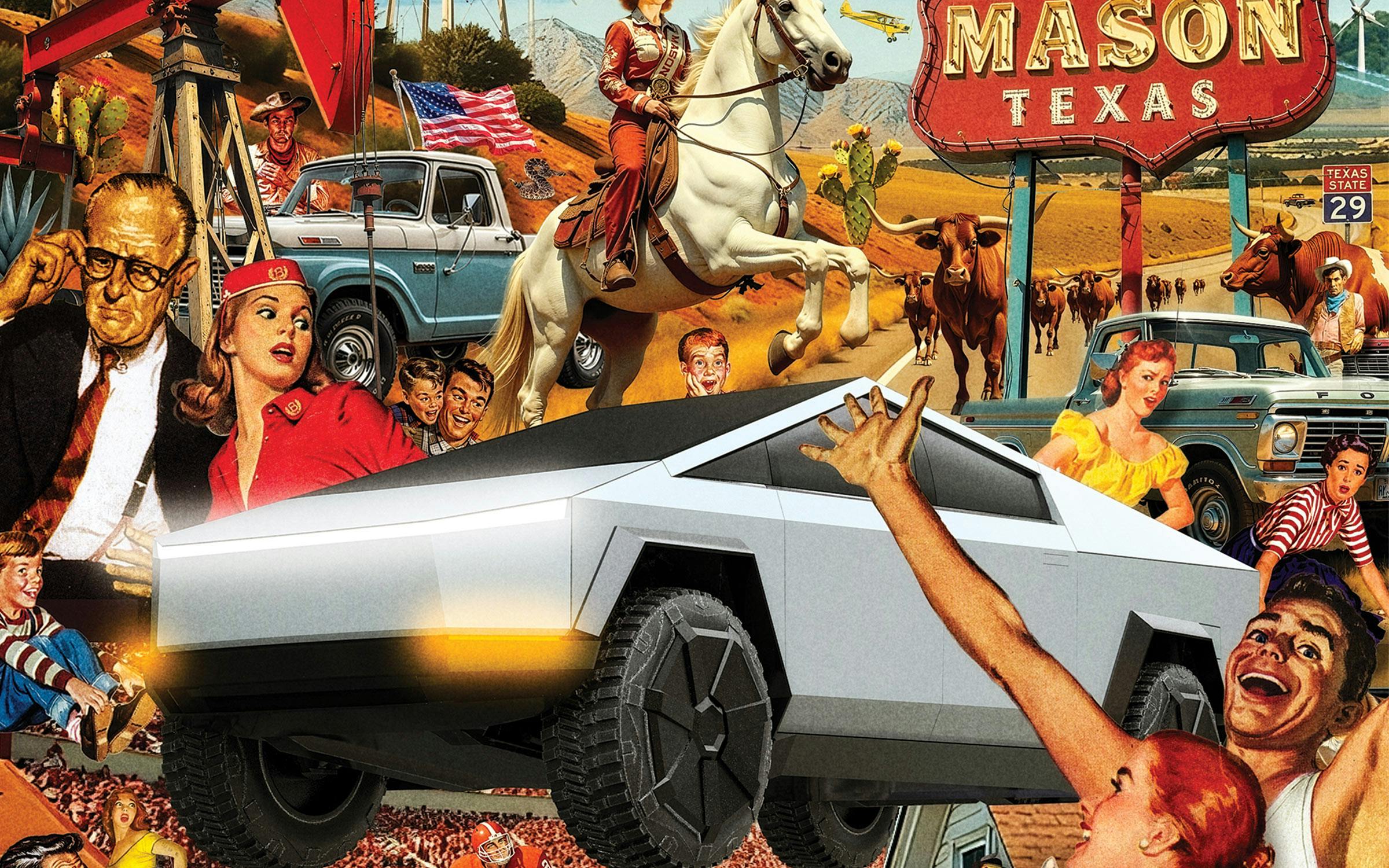

The parade is picture-perfect. It is also perfectly predictable, except for one wildly singular participant: a blinding collision of dystopian triangles known as the Cybertruck. Though it’s hard to tell by looking at it, the vehicle is an electric pickup made by Tesla, one of around 15,000 in existence at the time. The effect is dislocating, as though a lunar excursion module has been dropped into a Norman Rockwell painting.

I happen to be riding shotgun in this Cybertruck, a guest of its owner. I wave and smile. We cause a minor sensation. Everyone stares. Many point. The truck’s presence is so jarring that it inspires both laughter and bewilderment. “Did you spend all your money on that?” asks a teenage boy. “I’ve got a generator if you need one,” says one man with a wink as we pass.

From somewhere in the crowd a disembodied female voice says, “It’s kind of ugly.”

That it is.

But it’s both worse and more complicated than that.

Rewind to its late 2023 debut, and the Cybertruck, built in Tesla’s nearly mile-long Gigafactory, in Austin, seems in danger of becoming the most disastrous product launch in automotive history, in the company of such über-turkeys as the Ford Edsel, the Yugo, the DeLorean, and the Pontiac Aztek. The truck, relentlessly hyped by CEO Elon Musk, is a rolling catalog of promises unkept: It is years behind schedule. It costs around $100,000—more than twice what Musk said it would—and travels several hundred fewer miles on a battery charge than he originally projected. It hauls and tows far less than initially advertised and has nothing like the “full self-driving” capability that Musk touted.

But those aren’t the worst problems.

As it turns out, the truck is a compendium of defects and malfunctions. The list includes: dying batteries, sticky accelerators, wheel covers that gouge the tires, warping tailgates, trim pieces that fall off, malfunctioning wipers, software that seems to work only when it wants to, and body panels that don’t come close to fitting, leading to protruding edges that are so sharp they draw blood. The truck’s skin, an alloy made of stainless steel—it’s the first vehicle to feature this material since the ill-fated DeLorean—stains so easily that ordinary fingerprints are very difficult to remove. And so on. Not all Cybertrucks have all these defects, which is part of the problem: The product is maddeningly inconsistent. To read the posts on a Cybertruck owners’ forum is to enter a world of pain and suffering.

Then, too, Musk seems to be in a weird cultural and personal free fall. Once seen as a brilliantly quirky guy who built environmentally friendly cars and wanted to colonize Mars, he is now often identified as a conspiracy-spouting blowhard whose right-wing political views are alienating many of his customers. His 2022 purchase of Twitter, now X, has been an outright disaster. USA Today estimated in October that the company, which has lost large numbers of users and advertisers, is now worth less than a quarter of its $44 billion purchase price. His earth-tunneling, Bastrop-based “Boring Company,” which he said would help solve the world’s traffic woes, has become its own catalog of overhyped technologies and recurring failures to close a deal.

The temptation, of course, is to write off the ugly new truck as a piece of Musk-inflected hubris and industrial idiocy. Many critics already have. But—and this is a very large and capacious “but”—to do so is to ignore the last quarter century in which Musk has repeatedly pulled off what everyone said was impossible. With his dazzling Tesla Model S in 2012, he was the first to make electric cars cool and sell them for profit. When both industry experts and his own staff told him they couldn’t possibly make five thousand mass-market cars a week, they nonetheless produced the Model 3 at exactly that level and saved the company. He was bet against more heavily in the stock market than anyone in history. Most of those short sellers got burned. The market, which in 2018 made the money-losing Tesla more valuable than profit-rich General Motors, is still running massively in his favor. Today Tesla is the world’s most valuable car company.

Similarly, SpaceX, the company he founded in 2002, has, against all odds and predictions, launched more than four hundred rockets to date. Last year Musk put up more rockets than China. He is years ahead of the other private space companies, including Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin.

The question, then, is where the Cybertruck fits into Musk’s manic career. Is it the latest groundbreaking, rule-bending product from a company that has been successfully defying convention for the whole of its existence? Or is it a sign that he has finally gone off the deep end?

Like other products of Elon Musk’s empire, the Cybertruck is a creation of his overactive imagination. What you see clumping down the highway is at once incomprehensibly peculiar and exactly—exactly—the way he wants it. It’s an extension of his personality and must be understood that way. Someone who is worth well more than $300 billion can have what he wants, including what his critics have called a “low polygon joke” that looks like the box it came in. But the question persists: How did a vehicle this weird ever escape from a corporate design studio?

The simple answer is that it was bullied into existence. In 2017 Musk and Tesla’s design chief, Franz von Holzhausen, began exploring the idea of a pickup truck, which was logical because pickups are where a big chunk of the money is in the American car market. It was clear from the beginning that Musk did not want something that looked even remotely like a Ford F-150. He was thinking more along the lines of the Warthog, a futuristic vehicle from the Halo video game, or the flying car from Blade Runner. When some of his designers objected, as described in Walter Isaacson’s 2023 biography of Musk, he replied: “I don’t care if no one buys it. We’re not doing a traditional boring truck . . . I want to build something that’s cool. Like, don’t resist me.”

Early on, Musk established a radical rule that would determine both the look and much of the function of the Cybertruck: He decreed that it would be made of the same stainless steel alloy that SpaceX would soon use in its Starship. Stainless steel is hard and durable but very difficult to stamp, form, bend, cut, and weld into body panels for a car or truck. Its use, as Detroit entrepreneur John Z. DeLorean found out in the eighties, violates most of the car-building lessons of the past one hundred years. Even if you can get a single truck’s panels to fit flush with each other, it’s almost impossible to produce such uniform vehicles at scale.

The stainless requirement pushed Holzhausen and his team even further into the imagined future with a design that was all flat panels, sharp angles, and razor edges. Musk was thrilled. “That’s it,” he said, according to Isaacson’s biography. “I love it. We are doing that.” Unfortunately, Holzhausen told Isaacson, “The majority of people in the studio hated it. They were like, ‘You can’t be serious.’ It was just too weird.” When they pushed Musk to do market testing, he told them, “I don’t do focus groups.” (Musk and other Tesla executives weren’t available for interviews for this story.)

In November 2019, Musk stood on a stage in Hawthorne, California, where, amid thundering music, flashing lasers, and clouds of artificial smoke, he rolled out his silver trapezoid on wheels. There were cheers and, predictably, gasps. To demonstrate the toughness of the truck, Musk had his chief designer hit it repeatedly with a sledgehammer, without denting it. To show that it was bulletproof, he played a video of the door being shot with a 9mm. The test of its “armor glass” windows failed when two of them were shattered by a steel ball. He showed other videos of a Cybertruck winning a tug-of-war with an F-150 and pulling ahead of a Porsche 911 during a drag race. He got his biggest applause when he announced the base price: $39,900. The truck, the company said, would go into production in two years. Soon more than one million buyers would put down a deposit, initially just $100, on a Cybertruck.

Four years later the long overdue Cybertruck made its debut. Price: $100,000, which came with all of Musk’s other unfulfilled promises, and was fully in keeping with his past pledges to produce other Tesla products, including a tractor trailer, a new roadster, a robotaxi, and cars that fully drive themselves. That the Cybertruck was both deeply compromised by its design and visibly flawed was apparent from the start. The truck looked like a puzzle whose pieces didn’t quite fit together, like a high school shop project. In the parking lot of Tesla’s office in Austin, I saw Cybertrucks with half-inch gaps in their trunk panels and protruding, knife-sharp points where joints should have fit together. It was shocking to see this firsthand, especially in a vehicle that costs as much as a Range Rover.

“So much of this car is worst in class,” says Matt Farah, the host of The Smoking Tire, the country’s leading automotive podcast. “The panel gaps are atrocious. The wiper sticks out over the A-pillar. I wouldn’t let these flaws pass on a Sub-Zero refrigerator, let alone a six-figure truck. There are so many corners they have backed themselves into with this design.” Musk admitted that the stainless steel had created severe production problems. According to MotorTrend, in a 2023 conference call with analysts, he said, “We dug our own grave with the Cybertruck.”

I neglected to mention one other thing: The Cybertruck is completely, and unambiguously, thrilling to drive. When the parade in Mason was over, I steered the purple-wrapped pickup into the live oak woodlands and granite hills of the Llano Uplift. On the first straightaway, I opened it up.

The Cybertruck is a big, heavy thing, weighing more than three tons. If you didn’t know better, you might think it was also slow and cumbersome. It is actually rocketlike. I’m not saying that it caused the skin on my face to ripple and distort, but accelerating from 0 to 60 in 4.1 seconds was a fully physical experience. The effect of going from 40 miles per hour to 80 miles per hour was even more impressive. It’s effortless. You hit the, er, gas, and you are there in a little over one second. It’s just this side of alarming. My only regret was that a Dodge Charger Hellcat Redeye, the world’s fastest four-door muscle car, hadn’t pulled up alongside me at the light. The race would have been a dead heat. (My truck had two electric motors. If you want to enter Lamborghini territory, there’s a three-motor version, known as the Cyberbeast, that goes from 0 to 60 in 2.6 seconds.)

The Cybertruck may look like something from the Island of Misfit Toys, but it handles like a sports car. There are many technical reasons for this, but the two that the average car idiot like me can understand both relate to the steering. The truck is the first vehicle on the planet to have stand-alone “steer-by-wire,” a technology that allows the wheels to be moved with no mechanical linkage to the steering wheel. This is the way commercial jetliners are controlled: actuators and electronics instead of gears. The steering wheel—which looks more like a race car yoke—responds algorithmically to relatively small movements. There is no hand-over-hand wheel jockeying. The effect is light and precise. I loved it. Though Lexus and Infiniti have offered steer-by-wire systems, both had mechanical backups. The Cybertruck is the first to dare to go it alone. The other feature is four-wheel steering, in which the rear wheels can turn in opposite directions from the front. Don’t ask me how this works. But you can feel the precision, especially at low speeds or backing into parking places. The adaptive air suspension—which allows the vehicle to be raised as high as seventeen inches off the ground—makes the ride seem light, smooth, and comfortable. Reviews of the truck’s road performance have been almost universally good.

Which brings us back to the vexing question of why the quality of the construction is so bad. Part of the answer lies in Musk’s roots in Silicon Valley, the place where “fake it till you make it” is more than just a slogan. “There’s this disruptive mentality that says the legacy carmakers don’t know what they are doing, even though they have been doing it for one hundred years, and even though building a car is magnitudes more complicated than a mobile phone,” says Adrian Clarke, an automotive designer and columnist. “The thinking is, ‘Those companies are so inefficient. We can do it better.’ The idea is move fast and break stuff and we’ll fix it later.” So push it out the door like the latest high-tech gadget, and don’t worry too much about the details. Tesla, in fact, sees itself as a maker more of digital products than of cars. In January 2024 Musk tweeted that “Tesla is an AI/robotics company that appears to many to be a car company.”

Still, his noncar company does make things with wheels, and those things have been plagued with serious quality and reliability problems since the debut of its first car in 2008. In this sense the Cybertruck’s troubles are nothing new. Tesla cars—the Roadster, the Model S, Model X, Model 3, and Model Y—rank near the bottom of the industry for defects and dependability. A 2023 J.D. Power & Associates vehicle-dependability survey examining the 2020 model year found that Tesla ranked among the car industry’s worst performers. Consumer Reports, which had once raved over the Model S’s performance, withdrew its recommendation because of the car’s poor reliability.

Oddly, but fully in keeping with the company’s mystique, in 2020 Power ranked owners’ feelings about their vehicles, and Tesla scored highest. Buyers love them so much that they’re willing to put up with all sorts of problems. This is the Tesla paradox: “Customers would complain about the hilariously inept quality or service problems one minute,” wrote Edward Niedermeyer in his book Ludicrous, “and then extol the company as the future of the car business the next.”

To be fair, very few electric vehicles have had smooth rollouts. They have far more defects than their gas-dependent counterparts, though for reasons that may surprise critics of EVs. “In most cases, it’s not because they are EVs, per se,” says Dave Sargent, a vice president at J.D. Power who oversees auto research worldwide. “It’s because automakers tend to load up their EVs with lots of other new technologies and use them as a test bed to try out new things that don’t always turn out especially well. The power train is normally the least problematic part of an EV.”

The Cybertruck is fully inside this tradition, loaded with new technologies and new materials that tend to malfunction. Tesla has already recalled the Cybertruck six times. The fixes include a piece of the truck bed that could come loose while driving; a faulty windshield wiper motor; a pedal that can get stuck while accelerating; and a display time-lag on the rearview camera. The company also issued a “stop sale” on the truck’s wheel covers, which damage the tires after a few thousand miles of driving. These issues are but a few examples of the vast number of more commonplace complaints that pervade the internet but which the company has not addressed. Leaky truck bed covers, chronic error screens, and fast-dying batteries are subject to no recalls at all.

Yet Tesla’s chronic deficiencies, which would destroy a company like Ford or Toyota, have somehow not interfered with its relentless success, nor prevented Musk from becoming the richest man in the world, largely on the strength of Tesla’s stock price. It’s just the way Tesla rolls.

It’s late summer at the old Naval Air Station Alameda, or what’s left of it, just south of Oakland. The morning rains have cleared, the wind is rising, and fat white cumulus clouds are tumbling across San Francisco Bay. On an ancient runway a 480-horsepower Ford Mustang Mach-E GT screeches around an improvised track, filling the air with the smell of burning rubber. From a loudspeaker, a voice booms: “Buckle up for a hot lap in a Mach-E.” A line of young people wait to do just that, their eyes alight at the prospect.

The hot lap is part of Electrify Expo, the largest “e-mobility” festival in North America and about as far, culturally and technologically, from the retro-American, small-town charm of Mason, Texas, as you can get. All manner of electric cars and trucks are here, all the reasons Tesla’s overall market share is getting smaller: Hyundais, Fords, Kias, Volvos, Porsches, Rivians, BMWs, Lucids, Nissans, and more. All are available to drive. The festival also features e-bikes, e-scooters, e-skateboards, e-go-karts, and e-unicycles. Pretty much e-anything, as long as it has wheels.

Here, too, on the bay side of one of the runways, is the Cybertruck. Though more than a million enthusiasts have made reservations to buy one since 2019, and thousands now own one, no one has ever been able to take one for a test drive. You buy it on faith: in Tesla; in Musk. But shortly before the Expo, Tesla changed that policy, and the response is astounding. Most of the lines for test drives are short and the waits are minimal. The lines for the Volvo Polestar and the electric Ford F-150 Lightning are about twenty feet long. The Cybertruck line is several city blocks long, a minimum wait of two and a half hours. This has deterred no one. The line is mostly men, about 70 percent by my quick estimate. They are dressed in hoodies and gimme caps and T-shirts with Giants and A’s and Cal Berkeley logos. They talk about steer-by-wire and four-wheel steer and “full self-driving.” They argue about the battery range. They’re having fun.

I test-drive several vehicles, including the Cybertruck, but my focus is on the competition: the Rivian R1T and the Ford F-150 Lightning. Both are pickups and, like the Cybertruck, both are wildly fun to drive. The performance stats of the three vehicles, as measured by acceleration and braking, range, and towing capacity, are roughly comparable. The Rivian wins for speed and range, as tested by MotorTrend. The Cybertruck and the Rivian came in at around $102,000, the Ford at $94,000. (In October Tesla announced it was dropping the price of the Cybertruck by around $20,000.)

What the Lightning and R1T are not is weird. The Ford mimics the gas-powered F-150 in design. Its interior seems cozy and crowded with old-fashioned stalks and buttons and dials and gauges compared with the austere minimalism and stark computer screen of the Cybertruck. The Rivian falls somewhere between the two: very definitely an electric truck but without the far-out futurism. The Rivian R1T was MotorTrend’s truck of the year in 2022. The F-150 Lightning won the same award in 2023.

But the Cybertruck is the hit of the show. The people in line cannot know this yet, but for the month of July, the Cybertruck has surged to become the third-best-selling electric vehicle of any kind in the United States. This was in spite of generally bad press and a Tesla sales slump in the first two quarters of the year. In the year’s second quarter it was the best-selling e-truck in the United States and, according to Kelley Blue Book, the leader in the “ultra high-end” segment, which includes the Mercedes-Benz S-Class and the BWM 7 Series. But the truck’s July achievement was on an entirely different scale. The Cybertruck sold 5,172 units that month, taking third place (behind the Tesla models Y and 3) from the Mustang Mach-E SUV, even though the Mach-E was $60,000 cheaper. No one expected this.

Like so much else about the Cybertruck, the meaning of these sales numbers is hard to discern. The Ford F-150, America’s top-selling truck, sold roughly 750,000 units in 2023. Based on July sales, the Cybertruck will be lucky to sell 60,000 in 2024. Is that a success? That depends on who you talk to. “When they announced this product five years ago, I said it would never get made,” says Rory Carroll, the editor of the auto news and opinion website Jalopnik, which has been highly critical of the Cybertruck’s problems. “I didn’t believe they could ever deliver one. And they did. Even though there is really not a tremendous market for a product like the Cybertruck, that’s not the point. Tesla is really all about hyping the next thing. It is about Musk being able to boast: ‘I delivered the Cybertruck. So when I say I am going to do the next thing, you better believe me.’ If you look at Tesla as a stock market play, then I would think you have to say that the Cybertruck is successful.”

Like Musk himself, the Cybertruck is both loved and loathed. It’s perhaps not an accident that its debut coincides with, and has come to symbolize, Musk’s rightward political turn. He spent considerable time and money trying to reelect Donald Trump and has used X to amplify racist and antisemitic messages, along with a swirling fog of misinformation. He has also promoted the truck as though it belonged in one of those dystopian science fiction underworlds where, as The New York Times put it, “corporations reign over a teeming and violent underclass and cars often function as armored weapons.”

During a private event at the Austin factory in 2023, Musk stood in the bed of a Cybertruck and proclaimed it to be the “finest in apocalypse technology.” He said, “If you’re ever in an argument with another car, you will win.” He showed videos of the truck being shot with a Thompson submachine gun and an armor-piercing arrow.

Needless to say, no nonmilitary vehicle has ever been promoted quite this way. “What I wonder is, who exactly is shooting at you?” says The Smoking Tire’s Farah. “Why does someone need a truck that is in theory bulletproof? What he has built is a truck for people who are anticipating some kind of class war or race war. What he has built is really a truck that is optimized for running over crowds of people and tearing pedestrians to shreds.”

Are Musk’s politics hurting the Cybertruck, or helping it? It’s too early to say. The politics here don’t line up along conventional partisan lines. While Musk leaped onstage with Trump and dumped millions into his campaign, many Republican officials were busy demonizing electric car incentives. Musk has cozied up to Governor Greg Abbott, yet Texas depends hugely on oil and gas. It’s clear that Musk has angered many Tesla car owners, some of whom have bought bumper stickers that read, “I bought this before we knew Elon was crazy.” In California, new car registrations for Teslas declined for three consecutive quarters, according to a July report from the California New Car Dealers Association.

Those are the folks in La-La Land, of course, and those are Teslas, not Cybertrucks. There were 3,711 registered Cybertrucks in Texas by October. How Americans in general feel about the truck often comes down to how they feel about Musk himself. Do they believe in him? In spite of his exaggerations and broken promises, do they still consider him a singular visionary, a brilliant man who sees the future more clearly than anyone else?

Or is he simply a mad king who is fast running out of good ideas, as symbolized by his stumbles at X, his faltering launch of the Cybertruck, and his failure to deliver a fully self-driving car, which he has been promising as imminent since at least 2017? In October Musk unveiled an autonomous taxi that comes without a steering wheel or pedals and that he contends is the future of the car business. Production of the estimated $30,000 robot will begin, he said, in 2026. The response has been deeply skeptical. The next day Tesla stock fell by nearly 9 percent.

There are few comparable historical figures to help us predict the Cybertruck’s fate. There is, however, a cautionary tale from the annals of the automobile industry that might interest Mr. Musk. It features a flamboyant early-twentieth-century empire builder named William Crapo “Billy” Durant. Just as Musk used the money he made with PayPal to help launch Tesla, Durant parlayed the fortune he amassed as the nation’s biggest builder of horse-drawn carriages to take over the Buick Motor Company in 1904 and then launched General Motors in 1908. He lost control of GM to bankers in 1910, then managed to regain it in 1916. It would soon become the world’s largest industrial corporation. But Durant lost control again, this time for good, in 1920. He went bankrupt in the thirties and by the early forties was running a bowling alley.

Well, sic transit gloria. Musk, who says he is a student of history, has likely heard the name.

S. C. Gwynne, a former executive editor at Texas Monthly, is the author of Empire of the Summer Moon and many other books. He once covered the auto business from Detroit for Time.

This article originally appeared in the January 2025 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Most Polarizing Thing on Wheels!” Subscribe today.