Swastik pal

Swastik palOn a quiet Sunday evening in November 2005, a journalist in India’s Bihar state received a panicked phone call at home.

“The Maoists have attacked the prison. People are being killed! I’m hiding in the toilet,” an inmate gasped into the mobile phone, his voice trembling. The sound of gunshots echoed in the background.

He was calling from a jail in Jehanabad, a poverty-stricken district and, at the time, a stronghold of left-wing extremism.

The crumbling, red-brick, colonial-era prison overflowed with inmates. Spread across an acre, its 13 barracks and cells were described in official reports as “dark, damp, and filthy”. Originally designed for around 230, it held up to 800 prisoners.

The Maoist insurgency, which began in Naxalbari, a hamlet in West Bengal state in the late 1960s, had spread to large parts of India, including Bihar. For nearly 60 years, the guerrillas – also called Naxalites – have fought the Indian state to establish a communist society, the movement claiming at least 40,000 lives.

The Jehanabad prison was a powder keg, housing Maoists alongside their class enemies – vigilantes from upper caste Hindu private armies. All awaited trial for mutual atrocities. Like many Indian prisons, some inmates had access to mobile phones, secured through bribing the guards.

“The place is swarming with rebels. Many are simply walking out,” the inmate – one of the 659 prisoners at the time – whispered to Mr Singh.

On the night of 13 November 2005, 389 prisoners, including many rebels, escaped from Jehanabad prison in what became India’s – and possibly Asia’s – largest jailbreak. At least two people were killed in the prison shootout, and police rifles were looted amid the chaos. The United States Department of State’s 2005 report on terrorism said the rebels had even “abducted 30 inmates” who were members of an anti-Maoist group.

Prashant Ravi

Prashant RaviIn a tantalising twist, police said the “mastermind” of the jail break was Ajay Kanu, a fiery rebel leader who was among the prisoners. Security was so lax in the decrepit prison that Kanu stayed in contact with his outlawed group on the phone and through messages, helping them come in, police alleged. Kanu says this is not true.

Hundreds of rebels wearing police uniforms had crossed a drying stream behind the prison, climbed up and down the tall walls using bamboo ladders and crawled in, opening fire from their rifles.

The cells were open as food was being cooked late in the kitchen. The rebels walked to the main gates and opened them. Guards on duty looked on helplessly. Prisoners – only 30 of the escapees were convicts, while the rest were awaiting trial – escaped by simply walking out of the gates, and disappeared into the darkness. It was all over in less than an hour, eyewitnesses said.

The mass jail break exposed the crumbling law and order in Bihar and the intensifying Maoist insurgency in one of India’s most impoverished regions. The rebels had timed their plan perfectly: security was stretched thin due to the ongoing state elections.

AFP

AFP—

Rajkumar Singh, the local journalist, remembers the night vividly.

After getting the phone call, he rode his motorbike through a deserted town, trying to reach his office. He remembers the air was thick with gunshots ringing in the distance. The invading rebels were also trying to attack a neighbouring police station.

As he turned onto the main road, dim streetlights revealed a chilling sight – dozens of armed men and women in police uniforms blocking the way, shouting through a megaphone.

“We are Maoists,” they declared. “We’re not against the people, only the government. The jailbreak is part of our protest.”

The rebels had planted bombs along the road. Some were already detonating, collapsing nearby shops and spreading fear through the town.

Mr Singh says he pressed on, reaching his fourth-floor office, where he received a second call from the same prisoner.

“Everyone’s running. What should I do?,” the inmate said.

“If everyone’s escaping, you should too,” Mr Singh said.

Then he rode to the prison through the eerily empty streets. When he reached, he found the gates open. Rice pudding was strewn all over the kitchen, the cell doors were ajar. There was no jailor or policeman in sight.

In a room, two wounded policemen lay on the floor. Mr Singh says he also saw the bloodied body of Bade Sharma, the leader of the feared upper caste vigilante army of landlords called Ranvir Sena and a prisoner himself, lying on the floor. The police later said the rebels had shot him while leaving.

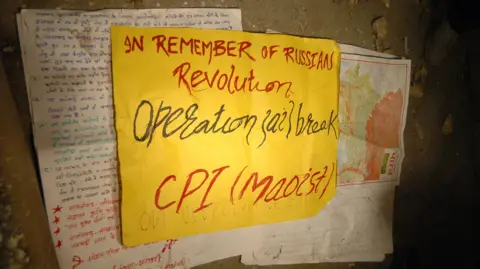

Lying on the floor and stuck to the walls were blood-stained handwritten pamphlets left behind by the rebels.

“Through this symbolic action, we want to warn the state and central governments that if they arrest the revolutionaries and the struggling people and keep them in jail, then we also know how to free them from jail in a Marxist revolutionary way,” one pamphlet said.

Prashant Ravi

Prashant Ravi—

A few months ago, I met Kanu, the 57-year-old rebel leader the police accuse of masterminding the jailbreak, in Patna, Bihar’s chaotic capital.

At the time of the incident, media reports painted him as “Bihar’s most wanted”, a figure commanding both fear and respect from the police.

Officers recounted how the rebel “commander” instantly took control during the prison break once he was handed an AK-47 by his comrades.

In a dramatic turn, the reports said, he “expertly” handled the weapon, swiftly changing magazines before allegedly targeting and shooting Sharma. Fifteen months later, in February 2007, Kanu was arrested from a railway platform while he was travelling from Dhanbad in Bihar to the city of Kolkata.

Almost two decades later, Kanu has been acquitted in all but six of the original 45 criminal cases against him. Most of the cases stem from the jailbreak, including that of the murder of Sharma. He has served seven years in prison for one of the cases.

Despite his fearsome reputation, Kanu is unexpectedly talkative. He speaks in sharp, measured bursts, downplaying his role in the mass escape that made headlines. Now, this once-feared rebel is subtly shifting his gaze toward a different battle – a career in politics, “fighting for poor, backward castes”.

As a child, Kanu spent his days and nights listening to stories from his lower-caste farmer father about Communist uprisings in Russia, China, and Indonesia. By eighth grade, his father’s comrades were urging him to embrace revolutionary politics. He says his defiance took root early – after scoring a goal against the local landlord’s son in a football match, armed upper-caste men stormed their home.

“I locked myself inside,” he recalls. “They came for me and my sister, ransacking the house, destroying everything. That’s how the upper castes kept us in check -through fear.”

Swastik Pal

Swastik PalIn college, while studying political science, Kanu ironically led the student wing of the Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which has waged a war against Maoism. After graduation, he co-founded a school, only to be forced out by the owner of the building. Upon returning to his village, tensions with the local landlord escalated. When a local strongman was murdered, Kanu, just 23, was named in the police complaint – and he went into hiding.

“Since then I have been on the run, most of my life. I left home early to mobilise workers and farmers, joined and went underground as a Maoist rebel,” he said. He joined the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist), a radical communist group.

“My profession was liberation – the liberation of the poor. It was about standing up against the atrocities of the upper castes. I fought for those enduring injustice and oppression.”

—

In August 2002, with a feared reputation as a rebel leader and a three million rupees bounty on his head – an incentive for people to report his whereabouts if they spotted him – Kanu was on his way to meet underground leaders and plan new strategies.

He was about to reach his destination in Patna when a car overtook him at a busy intersection. “Within moments, men in plainclothes jumped out, guns drawn, ordering me to surrender. I didn’t resist – I gave up,” he said.

AFP

AFPOver the next three years, Kanu was shuffled between jails as police feared his escape. “He had a remarkable reputation, the sharpest of them all,” a senior officer told me. In each jail, Kanu says he formed prisoner unions to protest against corruption – stolen rations, poor healthcare, bribery. In one prison, he led a three-day hunger strike. “There were clashes,” he says, “but I kept demanding better conditions”.

Kanu paints a stark picture of the overcrowding in Indian prisons, describing Jehanabad, which held more than double its intended capacity.

“There was no place to sleep. In my first barrack, 180 prisoners were crammed into a space meant for just 40. We devised a system to survive. Fifty of us would sleep for four hours while the others sat, waiting and chatting in the dark. When the four hours were up, another group would take their turn. That’s how we endured life inside those walls.”

In 2005, Kanu escaped during the infamous jailbreak.

“We were waiting for dinner when gunfire erupted. Bombs, bullets – it was chaos,” he recalls. “The Maoists stormed in, yelling for us to flee. Everyone ran into the darkness. Should I have stayed behind and been killed?”

Many doubt the simplicity of Kanu’s claims.

“It wasn’t as simple as he makes it sound,” said a police officer. “Why was dinner being prepared late in the evening when it was usually cooked and served at dusk, with the cells locked up early? That alone raised suspicions of inside collusion.”

Interestingly many of of the prisoners who escaped were back in jail by mid-December – some voluntarily, others not. None of the rebels returned.

When I asked Kanu whether he masterminded the escape, he smiled. “The Maoists freed us – it’s their job to liberate,” he said.

But when pressed again, Kanu fell silent.

The irony deepened as he finally shared a story from prison.

A police officer had once asked him if he was planning another escape.

“Sir, does a thief ever tell you what he’s going to steal?” Kanu replied wryly.

His words hung in the air, coming from a man who insists he had no part in planning the jailbreak.