[ad_1]

On September 24, 1950, not long after the Korean War began, Marine First Lieutenant H. J. Smith led a small group of his men up a hill near Seoul to attack a much larger enemy force. Pinned down on three sides, Smith pushed out in front of his fellow Marines, spurring them on as he directed the attack. Finally, after he had gone about two hundred yards, he was hit by automatic-weapons fire and killed. His men kept on, and 26 of them made it to the top of the hill and captured it. H. J. Smith was awarded the Navy Cross for heroism.

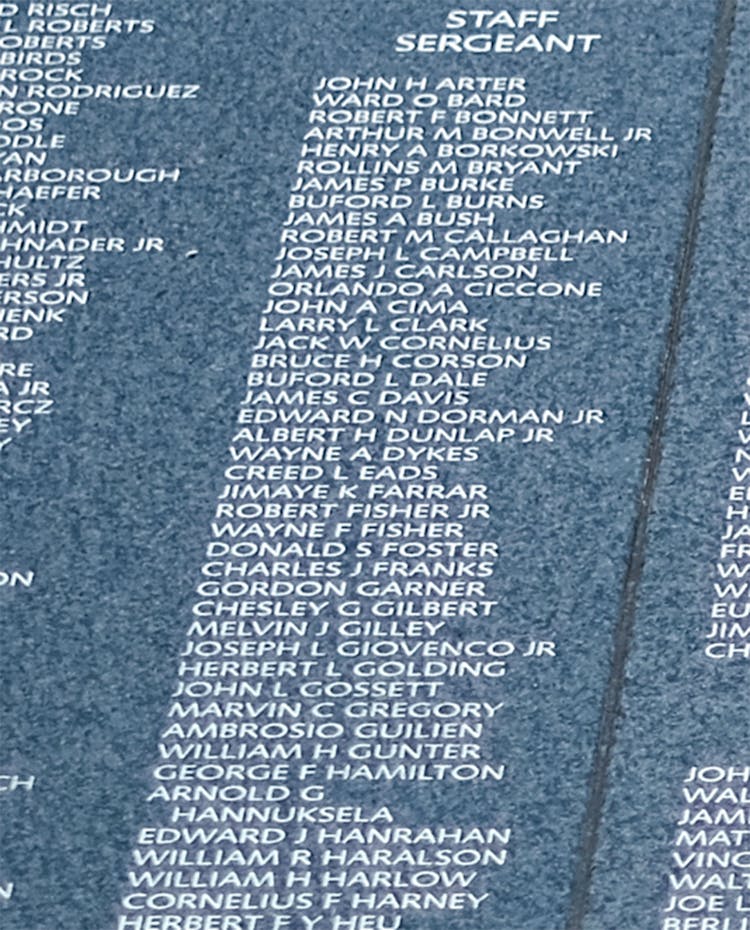

On Wednesday morning at 9 a.m., the Korean War Veterans Memorial Wall of Remembrance will be officially dedicated in Washington, D.C. On the granite half circle are etched the names of 36,634 dead Americans, plus another 7,174 Koreans who served and died under U.S. command. But there’s no Marine First Lieutenant H. J. Smith on the wall. There is, however, a “How J Smith,” and if anyone at the Korean War Veterans Memorial Foundation—the group in charge of building the wall—had done a simple internet search of this unusual name, they wouldn’t have found much. A search using Smith’s first initials, though, would have located the website of the Korean War Project, a database of war casualties maintained by Hal and Ted Barker, two brothers from Dallas. On the page for H. J. Smith, they would have seen that H.J. was his real name, he was from New Blaine, Arkansas, and that—according to a Barker brothers researcher—his nickname was Hog Jaw.

This isn’t the only mistake on the wall. As I wrote in a story published last week, the Barker brothers reckoned the wall would have many hundreds of errors in spelling and formatting. Well, now the foundation has released photos of the panels of the wall, and we can see for ourselves. The names of three Medal of Honors winners are misspelled or mis-formatted—including that of Ambrosio Guillen, whose name appears on the front of Guillen Middle School, in El Paso. On the wall, it is “Guilien.”

There are many mistakes like that—ones that, with a minimal amount of due diligence, could have been sussed out and fixed. For example, on the wall, under Marine lieutenant colonels, there’s “Edward R Gagenah”—but just two lines below him is Marine Lieutenant Colonel Edward R. Hagenah. Of course, they are one and the same person; Hagenah died on board a hospital ship in 1950. Why didn’t someone catch this?

“Asher Daniel” should be Asher Daniels; “Melvin E Sarkilanti” should be Melvin E. Sarkilahti. There are five men on the wall with the last name “Bear,” but then there are two unusual names that seem to make no sense: “Bear I Spotted” and “Bear J Young.” The slightest bit of curiosity and research would have led to the names of two young Army soldiers from Fort Berthold, North Dakota, who were killed in action in 1952: Ignatius Spotted Bear and Jasper Young Bear. “The Native American errors just break my heart,” Hal told me.

Hal and Ted, sons of a Korean War veteran, have been maintaining their database of casualties for more than thirty years—and amending it as families and war buddies of the dead reach out to them with information. The Barkers have essentially crowdsourced an accurate list of the dead. They spent years trying to notify the Army, Navy, Marines, and Air Force of mistakes, but the service branches told them there was little they could do; those entreaties had to come from family members. When, over the past few years, the foundation started gathering names for the wall, it used the Barkers’ site to fix some of the longtime errors in a piecemeal fashion. Unfortunately, the foundation didn’t make a serious effort to get a fully usable database that would have led to an almost completely accurate wall. And so the wall is full of unforgivable errors—botched names of men and women who died for their country.

Now that the wall is finally opening, Hal, who’s 74, is having a hard time processing it. “I don’t think I have ever been this depressed in my entire life,” he said. “I mean, I contacted everyone over the years—the White House, the vice president, the Secretary of Defense, the Secretary of the Interior, the foundation. Nobody cared. Nobody looked at it. I’ve been talking about those Medal of Honor errors for twenty years. I tried everything. They all said, basically, ‘It’s not our job.’ Nobody wanted to take any responsibility. Absent Hal and Ted Barker, who would have even known there’s a problem?”

[ad_2]

Source link