The new team’s offense was designed for a quarterback who didn’t show up for training camp and never set foot in the locker room. The biggest name—and body—on defense was ordered off the field after five plays, having been served with a restraining order that barred him from playing. And Texas’s only team in the inaugural season of the World Football League, fifty years ago, wasn’t even in Texas when the chaotic campaign lurched to its finish.

“Everything about covering the Houston Texans, it was almost surreal,” recalled Tony Pederson, who covered the team for the Houston Chronicle.

The WFL’s name was no accident—the upstart league launched with plans to locate franchises around the globe. That’s how San Francisco lawyer Steve Arnold bought the rights to a team in Tokyo but ended up owning the Texans instead.

And that mishap was only beginning.

Months before the league’s July 1974 kickoff, the Texans contacted longtime NFL coach Hank Stram, of the Kansas City Chiefs, to discuss a reported ten-year, $2 million deal that included partial ownership of the team. The Texans failed to lure Stram away from Kansas City, so they instead hired Jim Garrett, who’d left the New York Giants staff three months earlier to become a Dallas Cowboys assistant coach and moved his wife and eight children to Texas (including eight-year-old Jason Garrett, the future Cowboys coach). At a press conference meant to introduce Garrett to Houston fans, the coach said the hardest part of his new gig with the Texans would be “telling my wife we were moving again.”

WFL rosters that year were filled mostly with veteran NFL castoffs and young players who didn’t make pro rosters. Garrett chose for his quarterback Eldridge Dickey, a 28-year-old Houston native who was the first Black quarterback to be a first-round pro draftee. (The Oakland Raiders picked him in 1968, after Dickey’s stellar college career playing under center at Tennessee A&I.) In Oakland, however, Dickey only played receiver during the regular season (he made preseason appearances at quarterback). Garrett defended his incoming QB to the local media: “I don’t care if the guy’s a Hungarian monk. If he’s good enough to be the starter, he’ll be the starter.”

Except Dickey never joined the team. “I’ve tried my best to locate him and I can’t,” Jim Garrett told the Chronicle. “I’ve started looking to other individuals in the quarterback area.”

“There were constantly rumors about signings and big names about to come on board,” said Pederson, who became the Chronicle’s executive editor and is now both a senior national fellow at the Mississippi-based Overby Center for Southern Journalism and Politics and a professor emeritus in journalism at Southern Methodist University in Dallas.

Houston’s primary offensive player was running back Jim Nance, the American Football League’s player of the year in 1966. Former University of Houston rushing star Warren McVea, six years removed from his final season with the Cougars, was acquired a month into the season. At quarterback, after Dickey no-showed the season, the Texans turned to a pair of 32-year-olds—Mike Taliaferro, who’d backed up Joe Namath with the New York Jets, and Don Trull, a Houston Oiler in the 1960s who came out of retirement. Ex-NFL receivers Don Maynard and Warren Wells came through but didn’t stay long.

WFL teams were each scheduled to play twenty games, primarily on weeknights, while the NFL season consisted of just fourteen games. The Texans opened on the road against the Chicago Fire; they lost in a shutout, and Taliaferro and Trull both suffered injuries.

The Astrodome was about half full for the team’s July 17 home opener, a win over the Philadelphia Bell in front of a crowd of 26,227 fans, many of whom were drawn in by a “Nickel Beer Night” promotion.

Several WFL teams tried to compete with the NFL by signing stars from the premier pro football league to future deals that were meant to begin after the players’ current contracts expired. Most notably, a marquee trio of Super Bowl–winning Miami Dolphins—Larry Csonka, Jim Kiick, and Paul Warfield—signed to play in the WFL beginning in 1975. Cowboys quarterback Craig Morton, Roger Staubach’s backup, agreed to join the Texans in ’75.

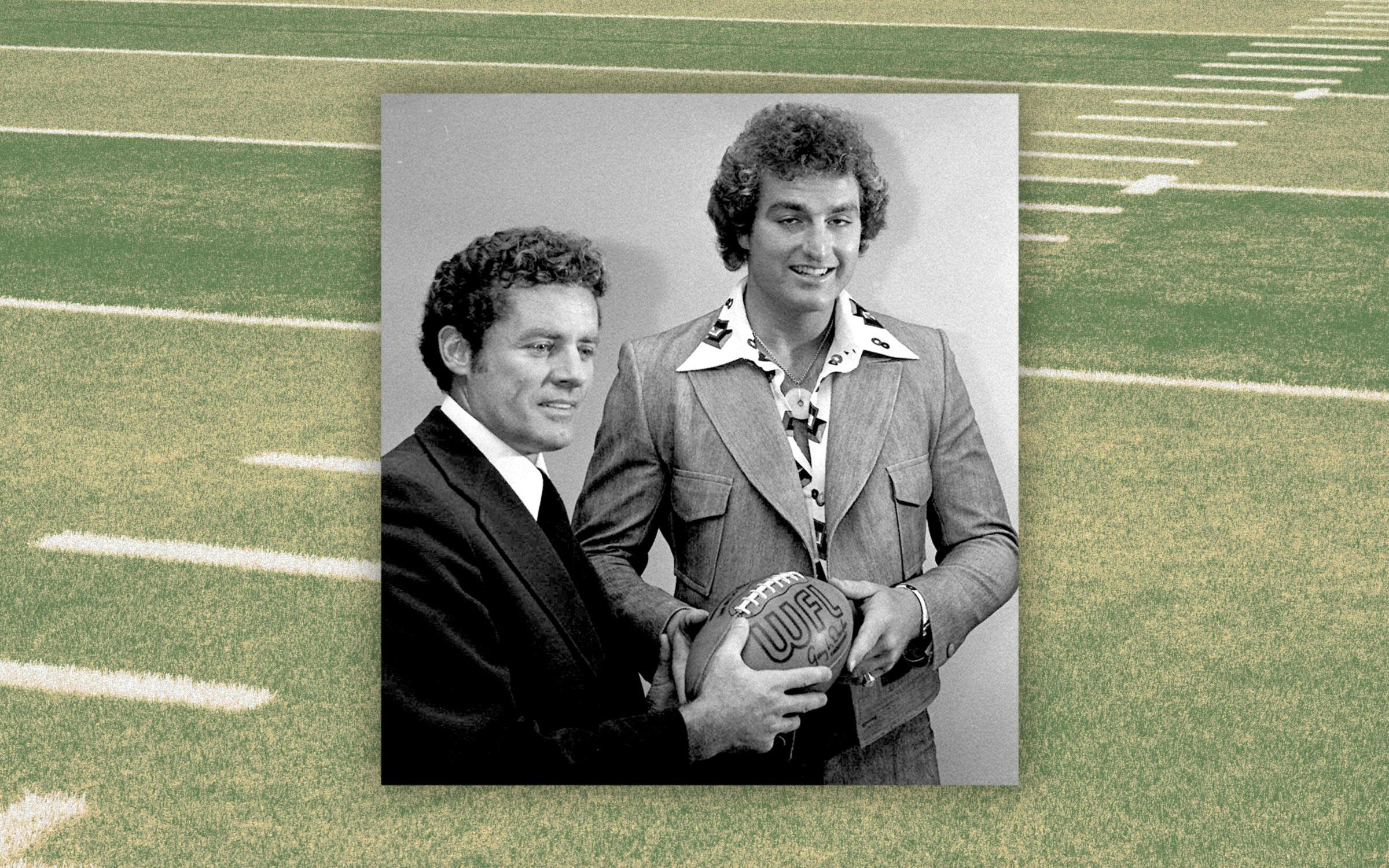

That legal strategy came to an abrupt halt in late August 1974, in Houston. The Texans had wooed Oilers defensive lineman John Matuszak, the top pick in the ’73 NFL draft, to immediately join the Texans despite an NFL contract that extended through 1977. At six foot eight and 280 pounds, Matuszak was huge in both stature and personality. “Tooz was great,” said longtime Houston sports radio host Barry Warner. “He was just so colorful. He would weight lift naked.”

One anonymous Oiler told the Chronicle’s Hal Lundgren that Matuszak “has been on an ego trip ever since he came in here.” Matuszak signed with the Texans for $1 million over five years on August 28, 1974, and insisted he didn’t do it for the money. “The Texan organization is conducive to a better way of life,” he said. “The air is a little fresher over here.”

That was a curious conclusion. The Texans were plagued with financial problems almost from the franchise’s inception, as were many other WFL organizations. The team made late payments to players during the preseason following reports that the disgruntled workers planned to sit out a scrimmage. Jim Garrett’s oldest son, also named Jim, was a fourteen-year-old ball boy with the Texans. He recalled his father telling the players at least once that they wouldn’t be receiving the next paycheck. “And they weren’t too happy about it,” the younger Jim said.

The ink was barely dry on Matuszak’s contract when he suited up for that night’s game at the Astrodome, against the New York Stars. With 10,126 rattling around the cavernous stadium—the Texans’ smallest home crowd up to that point—Matuszak got in for all of five plays. The coming-out party ended when the towering lineman was served a restraining order while standing on the sideline. The document barred him from playing until after a district court hearing on his contract dispute with the Oilers. After Matuszak received the papers, he defiantly waved them toward the fans. “What I remember is the police came on the field, maybe the first time in sports history, and took him out of the huddle,” said the younger Jim Garrett.

At the ensuing legal proceeding, more than one hundred members of the Oilers organization—players, coaches, and team personnel—were subpoenaed and jammed into the hallway outside the courtroom. According to Pederson, district judge Arthur Lesher said he couldn’t tell the players apart without a program. Four days later, Lesher ruled that Matuszak couldn’t play for the Texans. And he never played for them again—nor for the Oilers, who traded him to the Chiefs. Matuszak told the Kansas City Star he’d won a moral victory over his former NFL franchise.

There were no more victories of any kind for the Texans following their win over the Stars on the night of Matsuzak’s debut. They lost their next three games, with attendance dwindling to 9,861 for a September 11 home loss to the Honolulu-based Hawaiians, and dropped to 3–7–1 in the standings.

The sight of large swaths of empty seats was common at WFL games, particularly after the NFL season began, in mid-September. The WFL’s Detroit and Jacksonville franchises folded before season’s end. Financial losses in Houston began to compound, and soon the red ink led to a white flag. Arnold said he’d lost faith in the city’s desire to support the team, and the league took over franchise operations.

The league moved the team to Shreveport, Louisiana, a week after the Texans’ loss to the Hawaiians. “My father was outspoken about the move, like he was about the missing paychecks,” said the younger Jim Garrett, who’s now in his forty-third year teaching English at an all-boys high school near Cleveland. The WFL suspended Garrett the elder for conduct detrimental to the league, and he didn’t coach the team again.

The team was renamed the Shreveport Steamer, and its new local radio announcer was a pre-CNN Larry King. Shreveport finished 7–12–1, tied for last in its division. The squad earned a place in WFL history by playing before the league’s smallest crowd—750 fans, who showed up on a cold, rainy October weeknight in Philadelphia.

The WFL’s tumultuous 1974 season ended with a familiar coda. Minutes after the Birmingham (Alabama) Americans won the championship in their home stadium, county sheriff’s deputies interrupted the postgame celebration by entering the locker room and repossessing the team’s uniforms because of a $30,000 bill owed to a local sporting goods dealer.

Shreveport and the five other existing WFL franchises returned for a second season in 1975. Five new teams joined them, including the San Antonio Wings. The revamped league didn’t make it through the year before folding for good.

Jim Garrett returned to the Cowboys after his stint with the Texans and spent more than sixteen years in their scouting department, where he wrote the team’s initial assessment of Troy Aikman. Garrett died at age 87 in 2018.

Matuszak spent two contentious seasons with the Chiefs and then six with the Raiders. With Oakland, he won two Super Bowls and found an NFL home in an organization that embraced his shenanigans. Hampered by injuries at age 31, he left football for Hollywood. Matuszak had already appeared in the 1979 film adaptation of the satirical NFL novel North Dallas Forty. He later played the gentle giant Sloth in The Goonies and appeared in television series such as M*A*S*H and The Fall Guy. He died in 1989, at age 38, of heart failure near his home in California. The New York Times later reported his cause of death to be an accidental drug overdose.