Microplastics here, microplastics there, microplastics…everywhere? Research has recently shown that microplastics are found in our fish, beer, table salt, drinking water1, and most recently, in our own bodies.2

Microplastics are small pieces of plastic, less than 5mm in size, which come from a variety of sources. When large plastic debris such as a single-use coffee cup is thrown away, that cup exists forever. Plastic waste never fully biodegrades. Instead, it breaks down into smaller and smaller pieces that accumulate in our environment. Once microplastics are in our environment, they are nearly impossible to remove because of their size.

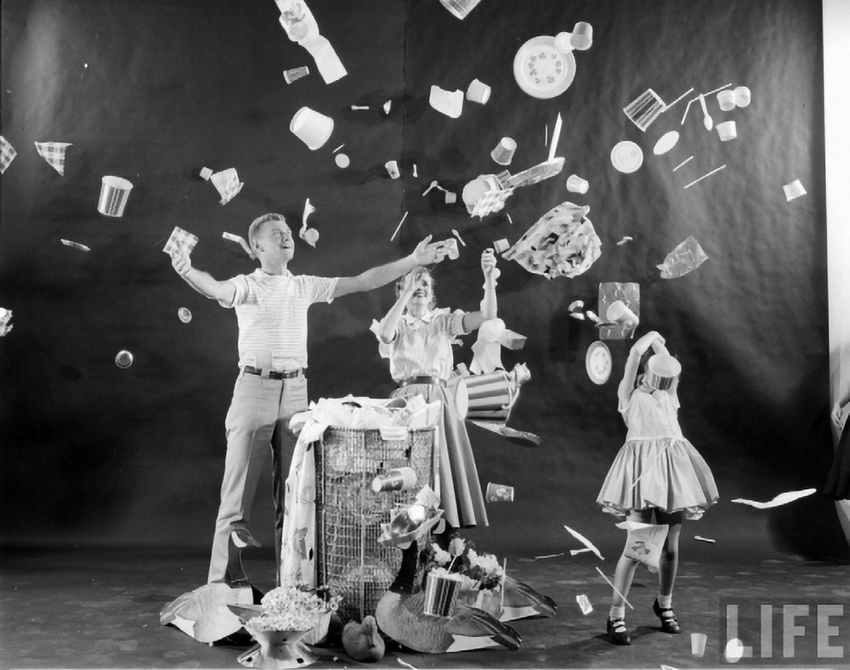

THROW AWAY CULTURE

In the early 1950s we began to see a rise in plastic dependency due to the convenience, availability, low cost, and durability of plastic products. This 1950s image from Life Magazine reads, “The objects flying through the air in this picture would take 40 hours to clean, except no household wife needs to bother.” With the widespread use of plastic, we started living in a convenience culture, where ease and instant gratification are prized above long-term benefits and sustainability. Although we have come a long way and are making strides towards a less plastic-centric environment, we still have significant work ahead of us.

Since the 1950s, humans have produced over 8 billion tons of plastic, most of which has already been disposed of and therefore still circulates in our environment today. When it comes to plastic pollution, out of sight is not the same as truly gone.

TEXTILE INDUSTRY

The most common type of plastics we dispose of are single-use food containers and textiles. The textile industry is the second most polluting industry in the world. Globally, there are 80 million new garments of clothing produced per year. Fast fashion and our overconsumption have drastically changed the way we view and purchase clothing, resulting in the average person buying more clothes and using them for less time.

One of the most common ways microplastics are entering our environment is through our washing machines. The clothing we wear is composed of synthetic, chemically treated fibres such as nylon, spandex, and polyester. Natural fibres such as wool, cotton, and bamboo do biodegrade; however, these products are also sometimes treated with dyes and chemicals to give them a desired look and feel. These chemicals slow the degrading process of natural fibres, allowing them to accumulate in our waters for years.

Cotton blue jeans are a great example of this process. Our jeans are synthetically dyed blue and are treated with chemicals to produce a soft or textured feeling. In addition, the jeans are composed of mixed fibres, allowing synthetic fibres to give our jeans that stretchy comfort. The cotton in the jeans will break down more quickly, leaving the synthetic stretchy fibres behind.4

MICROFIBRES IN THE GREAT LAKES

A single load of laundry can release up to 700,000 microfibres, which can end up in our water in two ways. Firstly, these fibres bypass the wastewater treatment plant and flow into the water. Secondly, these fibres make their way into waterways through runoff as they are spread on agricultural land through sewage sludge. Waste Water Treatment Plants are unsung heroes of microfibre collection. They have the ability to capture up to 99% of microfibres, which are then caught in the sewage sludge. In an effort to recirculate nutrients and minimize waste, that sewage sludge is spread onto agricultural fields as a form of fertilizer. As wind and rainfall occur, the microfibres trapped in that sludge make their way back into the waterway through natural runoff. The concentration of microplastics in the Great Lakes is equal to or greater than the concentration found within ocean currents like the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

Our plastic consumption is bad for our ecosystems and our health. A 2021 study sampled over 300 fish from Lake Ontario, the Humber River, and Laker Superior, finding that all the fish had microplastics in them, with most being microfibres.6 These plastic fibres have a profound impact on our fish, as their small size makes them easily consumable by microorganisms, fish, and other wildlife. Over time, plastics can bioaccumulate within the food chain. Some studies have found that microfibres cause stunted growth, malnourishment, and starvation. Such impacts contribute to a significant ripple effect on the emergence of the food chain.7 8

These fibres are impacting any creature that eats, drinks, and breathes, including us. Studies have found that on a weekly basis, humans consume one credit card size worth of microplastics, with higher consumption amounts among those who use products such as bottled water and coffee pods.9 The extent to which microplastics affect humans is still unknown.

Lucky for us and our environment, there are tangible solutions to this microplastic problem! One example is microfibre filters. These external, reusable filters can be connected to your washing machine discharge hose to capture microfibres shed from the wash. As your washing machine discharges wastewater, the microfibre filter captures the fibres in the effluent, preventing it from washing down the drain.

PARRY SOUND & COLLINGWOOD

In 2019, Georgian Bay Forever teamed up with the University of Toronto’s Rochman Lab to study how effectively washing machine filters reduce microfibre emissions. The study found by testing the wastewater treatment effluent before and after filters were installed that the microfibre emissions were reduced by an average of 41%.10 Such a significant reduction could also have been influenced by behavioural changes because of campaigning and education programs going on at the time.

In total, over the length of this two-year study, nearly 50 pounds of microfibre lint was diverted from Georgian Bay’s watershed—the same weight as a small mattress. Each milligram of lint contained 28-423 individual microfibres. This means that somewhere between 639 million to 9.7 billion microfibres were prevented from entering the water. In a large city such as Toronto, an initiative like this could prevent 12 to 166 trillion microfibres from entering our Great Lakes.11

Collingwood and the surrounding areas are working to divert more microfibres by distributing 300 free microfibre filters as part of another two-year study ending March 2023. Through this study, Georgian Bay Forever hopes to discover how much microfibre lint is diverted and compare the amount to the Parry Sound results.

WHAT CAN YOU DO?

Fighting plastic pollution can often feel overwhelming. However, there are many steps we can take on an individual level to reduce plastic pollution.

Here are 10 ways you can prevent microfibre pollution:

- Use cold water. Research has shown that polyester sheds more fibres at higher temperatures. Washing with cold water helps to save on your utility bills and preserves your clothing as it will help to prevent fraying, shedding, and fading.

- Use front load washing machines. Hartline’s study shows that front load washing machines had seven times less microfibres shed than top load machines.

- 13Get a microfibre filter. Depending on the brand, an external filter can capture up to 89% of microfibres! There are many filters on the market for purchase, so be sure to do your research. If you live in the Collingwood, Wasaga Beach, or The Blue Mountains area, volunteer to have a filter installed for free!

- Avoid fast fashion. Reduce your purchases by buying used clothing from vintage or thrift stores, swap with friends, rent or borrow clothes, or purchase higher quality fabrics when possible.

- Reuse and repurpose clothing and plastic. Find ways to repair and repurpose textiles by turning them into cleaning rags or tote bags, or by donating them.

- Refuse to use plastic. Try to make it a habit to have reusable items on hand such as travel mugs and water bottles, cloth and mesh produce bags, reusable cutlery, and beeswax wraps. Not using plastic in the first place is more effective than recycling used plastics.

- Choose products and retailers with less packaging. Where possible, make a choice to buy from local brands that reduce plastic packaging or use recycled packaging.

- Research recycling. Ensure that the materials you are putting in the recycling can be recycled by your municipality and are not contaminated.

- Take Action with Nature Canada’s 30×30 Defend Nature campaign to demand Canada’s leaders to meet their goal to protect 30% of land, freshwater and oceans by 2030.

- Write your local MPP to demand support for Ontario Bill 102 to get filters on future washing machines at the manufacturer level. Georgian Bay Forever has designed a template form to guide you in the process here.

Microfibre filters are effective at both small- and large-scale settings. These filters play a large role in helping us reduce microfibres in our environment. However, implementation of filters in washing machines as a plastic pollution solution requires support by legislation, innovation, and most importantly, education and awareness to drive change. Together, by increasing our awareness, joining voices with our community, and making small changes in our personal lives, we can work together to protect the health of our local ecosystems as well as our families.

Ashley Morrison is the Project Manager for Collingwood Divert and Capture: The fight to keep microplastics out of our water at Georgian Bay Forever.

1 Zhang, Qun, et al. “A Review of Microplastics in Table Salt, Drinking Water, and Air: Direct Human Exposure.” Environmental Science & Technology, vol. 54, no. 7, 2020, pp. 3740–3751., https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b04535.

2 Jenner, Lauren C., et al. “Detection of Microplastics in Human Lung Tissue Using Μftir Spectroscopy.” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 831, 2022, p. 154907., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154907.

3 Throwaway living . Life Magazine, 1 August 1955, vol. 39, issue 5, pp. 43–44.

4 Zaman, Atiq & Newman, Peter. (2021). Plastics: are they part of the zero-waste agenda or the toxic-waste agenda?. Sustainable Earth. 4. 10.1186/s42055-021-00043-8.

5 Munno, Keenan, et al. “Microplastic Contamination in Great Lakes Fish.” Conservation Biology, vol. 36, no. 1, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13794.

6 Munno, Keenan, et al. “Microplastic Contamination in Great Lakes Fish.” Conservation Biology, vol. 36, no. 1, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13794.

7 Foley C. J., Feiner Z. S., Malinich T. D., Höök T. O.. (2018). A meta-analysis of the effects of exposure to microplastics on fish and aquatic invertebrates. Science of the Total Environment, 631-632, 550–559

8 Bucci K., Tulio M., & Rochman C. M. (2019). What is known and unknown about the effects of plastic pollution: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Ecological Applications, 30, e02044.

9 K. Senathirajah, T. Palanisami, University of Newcastle, How much microplastics are we ingesting? Estimation of the mass of microplastics ingested.Report for WWF Singapore, May 2019

10 Erdle, Lisa M., et al. “Washing Machine Filters Reduce Microfiber Emissions: Evidence from a Community-Scale Pilot in Parry Sound, Ontario.” Frontiers in Marine Science, vol. 8, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.777865.

11 Erdle, Lisa M., et al. “Washing Machine Filters Reduce Microfiber Emissions: Evidence from a Community-Scale Pilot in Parry Sound, Ontario.” Frontiers in Marine Science, vol. 8, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.777865.

12 Erdle, Lisa M., et al. “Washing Machine Filters Reduce Microfiber Emissions: Evidence from a Community-Scale Pilot in Parry Sound, Ontario.” Frontiers in Marine Science, vol. 8, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.777865.