In the early 1940s, Elroy Williams attended third grade in a simple wooden building in rural Bastrop County. The structure lacked indoor plumbing and relied on a wood stove for heat. But the walls were lined with windows that let in plenty of light and could be opened in the warmer months to create a pleasant cross breeze. The students’ parents brought firewood to the school in winter, and some of the older kids, in seventh and eighth grade, helped cut it to size. This was a Rosenwald school—one of nearly five thousand schools built between 1912 and 1937 in a historic initiative that transformed public education for African Americans in the rural South.

Williams’s future wife, Sophia, went to another Rosenwald school a few miles away, in nearby Cedar Creek. The Hopewell school had been built on land her grandparents bought after emancipation, holdings that included more than eighty acres purchased from the owner of the plantation where her grandfather had been enslaved. In early 1919, her widowed grandmother learned that a program launched by Black educator Booker T. Washington and Julius Rosenwald, the president of Sears, Roebuck and Company, was building schools for African American children. She donated roughly an acre for the construction of a schoolhouse, and her daughter—Sophia’s mother—was the first teacher.

After college, Elroy and Sophia Williams settled in Bastrop County, where they were teachers and Sophia later served on the Bastrop school board. Elroy’s elementary school had been lost to fire, but the Hopewell structure still stood, although it was in bad shape. The Williamses led an effort to restore it, and today the former Hopewell Rosenwald School in Cedar Creek is a community center. “We might not have gotten as good an education as we did if it had not been for Julius Rosenwald and those schools,” Elroy Williams, who is 91, said in a recent interview.

The story of the Hopewell school is one of many told in “A Better Life for Their Children: Julius Rosenwald, Booker T. Washington, and the 4,978 Schools That Changed America,” on view at the Bullock Texas State History Museum in Austin through February 23. The poignant exhibit showcases elegant black and white photographs by Atlanta-based Andrew Feiler, who documented more than one hundred of the remaining buildings and interviewed former students and teachers about the schools’ enduring influence. He also authored a 2021 book with the same title as the exhibit.

Texas once had approximately 470 of these schools, plus several dozen teachers’ houses and industrial shops, where students learned trade skills. Funded primarily by donations from Rosenwald, who amassed a huge fortune through his mail-order business, the schools were built in rural areas across 82 counties, most of them in East and Central Texas. A Texas Historical Commission survey has determined that 39 of the buildings still stand, and 21 have been demolished. The fates of the rest are unknown.

The school-building program began in 1912, a year after Rosenwald and Washington met. Rosenwald, the son of German Jewish immigrants, lived in Chicago but was attuned to the plight of African Americans in the Jim Crow South. “I do not see how America can go ahead if part of its people are left behind,” he wrote. Washington, born enslaved in Virginia, pursued an education after emancipation and taught at the institution today known as Hampton University, in Virginia. He was tapped to serve as the founding principal for the Tuskegee Institute, established in 1881 as a training school for Black teachers. It’s now a comprehensive university near Montgomery, Alabama.

By the time Rosenwald and Washington met at a fundraiser, Rosenwald had become president of Sears and was well on his way to making it the world’s largest retailer. He also had read Washington’s autobiography, Up From Slavery. Rosenwald’s generosity was partly an enactment of the Jewish ideals of tzedakah, which connotes both charity and justice, and tikkun olam, or actions intended to repair the world. His thinking was also shaped by the progressive ideas of his Chicago synagogue’s influential rabbi, Emil Hirsch, who supported workers’ rights and economic justice. Both Hirsch and Rosenwald were early supporters of the NAACP, which was founded by a multiracial coalition in 1909 in the wake of a race riot started by a white lynch mob in Rosenwald’s hometown of Springfield, Illinois.

Rosenwald knew that in the era of segregation, Black children in the South learned in substandard facilities that used outdated materials—when schools were available to them at all. Black schools received scant public funding, and kids often had to make do by attending makeshift schools in private homes, churches, or even outdoors. When Rosenwald launched his philanthropic program, he included a $25,000 gift (more than $810,000 in today’s dollars) to the Tuskegee Institute. Washington decided to direct some of the money toward building schools for Black children in rural Alabama. The duo built six schools near Tuskegee and, encouraged by their success, expanded the program to fifteen Southern and border states. They ultimately built 4,978 schools in partnership with local communities, which had to contribute labor or funds to the project. One in five Black schools in the rural South in the twenties was a Rosenwald school.

Several of Feiler’s photos show the empty interiors of these buildings, now restored but devoid of students. Light pours through the tall windows, warming shiplap walls and scuffed wood floors. American flags and small portraits—in one photo, of Abraham Lincoln; in another, of Rosenwald—provide minimal decoration. Feiler’s text panels explain that the schools were designed by a team of Tuskegee architects who laid out guidelines for the buildings that emphasized modesty, in part to avoid raising the ire of local whites. The buildings generally lacked electricity, indoor plumbing, and heating.

Only about five hundred of the Rosenwald schools still stand—a tenth of the total. Roughly half of those buildings have been restored and now serve as community spaces of some kind. These include the Hopewell school in Cedar Creek and the Pleasant Hill school in Linden, in northeast Texas, now home to a quilting group whose handiwork commemorates Black history. The Columbia Rosenwald School in Brazoria County was restored and opened as a museum in 2009, and efforts are underway in Rusk County, southeast of Tyler, to rehabilitate the Concord school for future use as a museum.

Feiler’s photos show other schools that have been conceded to the ravages of time. A schoolhouse in South Carolina stands in disrepair, surrounded by the gravestones of an expanding cemetery. Rosenwald Hall in Lima, Oklahoma, sits abandoned, bricks crumbling from one corner. It was one of at least eleven schools built in all-Black communities formed in Oklahoma after the Civil War. These towns were founded by the descendants of people enslaved by native tribes in the southeastern U.S., some members of which had adopted slavery as a means of assimilating into white society. The U.S. government forcibly relocated these tribes, along with the Black families they had enslaved, to land west of the Mississippi River in the 1830s and 1840s. The Lima structure is the only remaining Rosenwald school built in such a community.

These deteriorating schools feel like prizes forfeited by their communities. The buildings themselves are unremarkable, but they are artifacts of a significant time in history. When the buildings disappear, so do the visible reminders of the communities’ past. The preservation projects that restored some schools began with efforts to repair the roof and stabilize walls, but they ultimately preserved the human stories that unfolded inside those walls.

The legacy of the Rosenwald schools is the people who attended them, and “A Better Life” balances the photos of empty classrooms and buildings with moving portraits of former students and teachers. The late Georgia Congressman John Lewis, pictured in the exhibit, was one of several prominent civil rights leaders who were Rosenwald alumni. Others include Maya Angelou, poet and northern coordinator for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference; attorney, activist, and Episcopal priest Pauli Murray; and several members of the Little Rock Nine, who integrated that city’s Central High School. Rosenwald schools often were used as meeting spots for civil rights organizers.

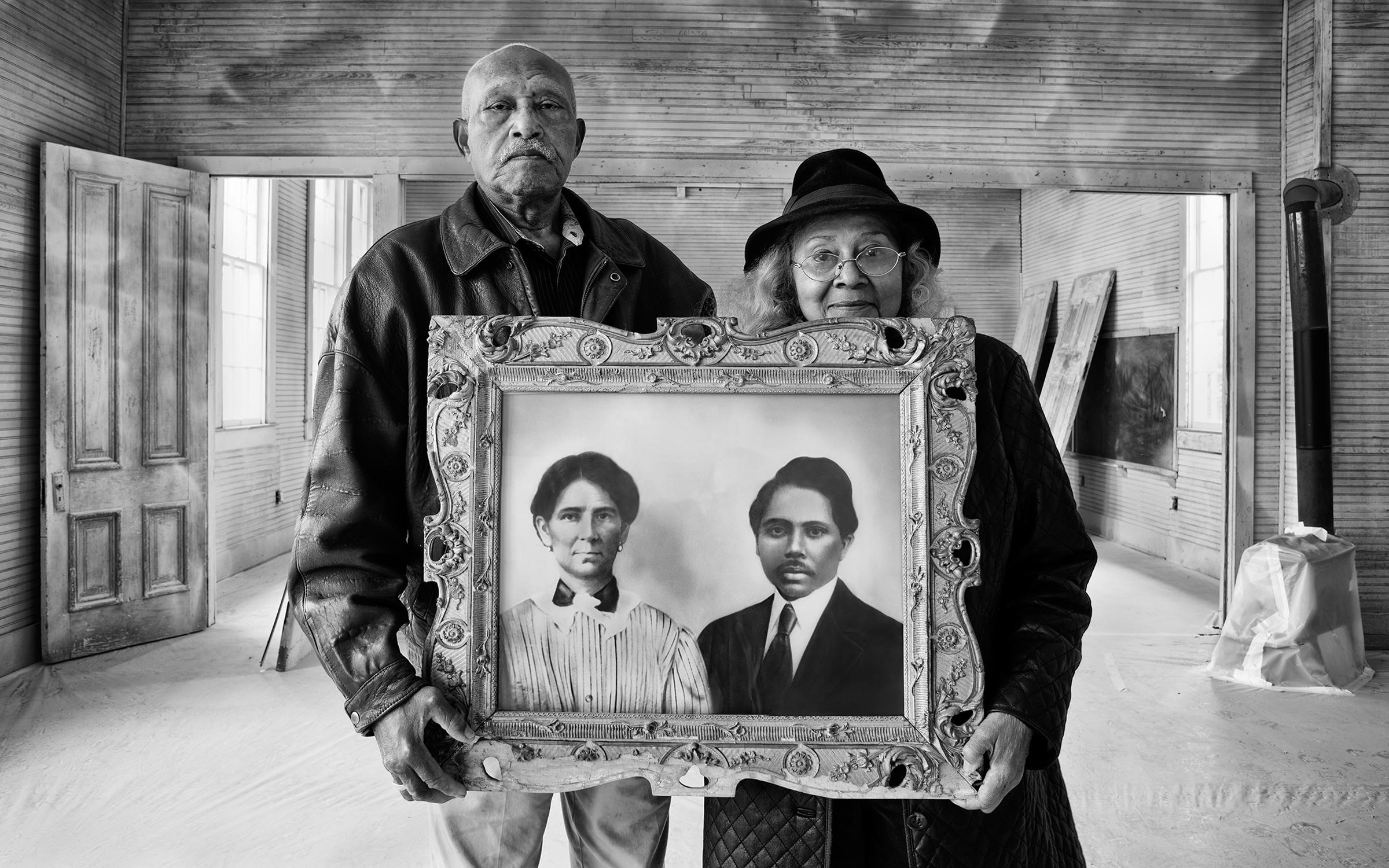

But less famous alumni also benefited. Rosenwald schools have been credited for shrinking the educational gap between Black and white Americans and for contributing to social mobility. One portrait features the grandfatherly Brinkley brothers of Tennessee, who attended a Rosenwald school and went on to earn graduate degrees, teach in public schools, and eventually renovate their old classroom building. In another particularly poignant shot, Elroy Williams stands with his wife, Sophia, who died in 2019, in the Hopewell school. The two hold a portrait of Sophia’s grandparents, who bought the land where the school is today. On February 8, the Bullock Museum will screen Rosenwald, a film by Aviva Kempner, and host a discussion about school preservation in which Elroy Williams will participate.

“What changed my life was having the opportunity to come to school,” Leroy Diggs, an alumnus of the Columbia Rosenwald School, told a Texas Historical Commission documentarian in 2015. Feiler’s photos and text offer a glimpse inside the rooms where such changes began.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, a portion of your purchase goes to independent bookstores and Texas Monthly receives a commission. Thank you for supporting our journalism.